Ancient Egyptian mathematics

The ancient Egyptians utilized a numeral system for counting and solving written mathematical problems, often involving multiplication and fractions.

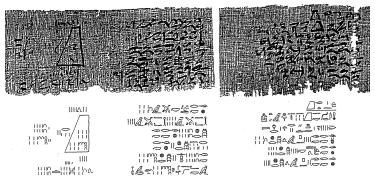

Evidence for Egyptian mathematics is limited to a scarce amount of surviving sources written on papyrus.

From these texts it is known that ancient Egyptians understood concepts of geometry, such as determining the surface area and volume of three-dimensional shapes useful for architectural engineering, and algebra, such as the false position method and quadratic equations.

Written evidence of the use of mathematics dates back to at least 3200 BC with the ivory labels found in Tomb U-j at Abydos.

[1] Further evidence of the use of the base 10 number system can be found on the Narmer Macehead which depicts offerings of 400,000 oxen, 1,422,000 goats and 120,000 prisoners.

[2] Archaeological evidence has suggested that the Ancient Egyptian counting system had origins in Sub-Saharan Africa.

[3] Also, fractal geometry designs which are widespread among Sub-Saharan African cultures are also found in Egyptian architecture and cosmological signs.

These texts may have been written by a teacher or a student engaged in solving typical mathematics problems.

In the workers village of Deir el-Medina several ostraca have been found that record volumes of dirt removed while quarrying the tombs.

[1][6] Current understanding of ancient Egyptian mathematics is impeded by the paucity of available sources.

The sources that do exist include the following texts (which are generally dated to the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period): From the New Kingdom there are a handful of mathematical texts and inscriptions related to computations: According to Étienne Gilson, Abraham "taught the Egyptians arythmetic and astronomy".

In Rhind Papyrus Problem 28, the hieroglyphs (D54, D55), symbols for feet, were used to mean "to add" and "to subtract."

would be repeatedly subtracted from the multiplier to select which of the results of the existing calculations should be added together to create the answer.

For instance problem 19 asks one to calculate a quantity taken 1+1/2 times and added to 4 to make 10.

[8] The use of the Horus eye fractions shows some (rudimentary) knowledge of geometrical progression.

[8] The ancient Egyptians were the first civilization to develop and solve second-degree (quadratic) equations.

Additionally, the Egyptians solve first-degree algebraic equations found in Rhind Mathematical Papyrus.

The examples demonstrate that the Ancient Egyptians knew how to compute areas of several geometric shapes and the volumes of cylinders and pyramids.