Ancient Egyptian funerary practices

These rituals included mummifying the body, casting magic spells, and burials with specific grave goods thought to be needed in the afterlife.

Although specific details changed over time, the preparation of the body, the magic rituals, and grave goods were all essential parts of a proper Egyptian funeral.

Although no writing survived from the Predynastic period in Egypt (c. 6000 – 3150 BCE), scholars believe the importance of the physical body and its preservation originated during that time.

[3](p 7) From the Predynastic period through the final Ptolemaic dynasty, there was a constant cultural focus on eternal life and the certainty of personal existence beyond death.

Without any written evidence, except for the regular inclusion of a single pot in the grave, there is little to provide information about contemporary beliefs concerning the afterlife during that period.

[10](pp 71–72) By 3600 BCE, Egyptians had begun to mummify the dead, wrapping them in linen bandages with embalming oils (conifer resin and aromatic plant extracts).

[11][12] By the First Dynasty, some Egyptians were wealthy enough to build tombs over their burials rather than placing their bodies in simple pit graves dug into the sand.

The rectangular, mudbrick tomb with an underground burial chamber, termed a mastaba in modern archaeology, developed in the Early Dynastic period.

Grave goods expanded to include furniture, jewelry, and games as well as the weapons, cosmetic palettes, and food supplies in decorated jars known earlier, in the Predynastic period.

Among the elite, bodies were mummified, wrapped in linen bandages, sometimes covered with molded plaster, and placed in stone sarcophagi or plain wooden coffins.

Wooden models of boats, scenes of food production, craftsmen and workshops, and professions such as scribes or soldiers have been found in the tombs of this period.

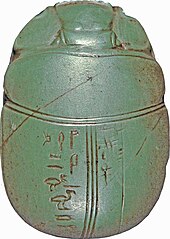

Coffin texts and wooden models disappeared from new tombs of the period while heart scarabs and figurines shaped as mummies were now often included in burials, as they would be for the remainder of Egyptian history.

Such graves reflect very ancient customs and feature shallow, round pits, bodies contracted, and minimal food offerings in pots.

People of the elite ranks in the Eighteenth Dynasty placed furniture as well as clothing and other items in their tombs, objects they undoubtedly used during life on earth.

Beds, headrests, chairs, stools, leather sandals, jewelry, musical instruments, and wooden storage chests were present in these tombs.

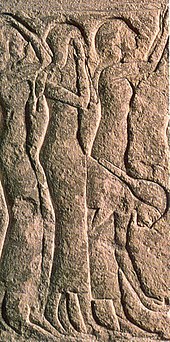

The funeral ceremony, the funerary meal with multiple relatives, the worshipping of the deities, even figures in the underworld were subjects in elite tomb decorations.

[10](p 103) Substances recovered from vessels at an embalming workshop in Saqqara dated back to the 26th Dynasty contained extracts from juniper bushes, cypress and cedar trees in the eastern Mediterranean region, in addition to bitumen from the Dead Sea, locally produced animal fats and beeswax, and ingredients from distant places such as elemi and dammar from southeast Asia; while Pistacia resin and castor oil were used in particular for the treatment of the head.

[21] Before embalming, or preserving the dead body as to delay or prevent decay, mourners, especially if the deceased had high status, covered their faces with mud, and paraded around town while beating their chests.

[21] After embalming, the mourners may have carried out a ritual involving an enactment of judgment during the Hour Vigil, with volunteers to play the role of Osiris and his enemy brother Set, as well as the deities Isis, Nephthys, Horus, Anubis, and Thoth.

[24] In addition to the reenactment of the judgment of Osiris, numerous funeral processions were conducted throughout the nearby necropolis, which symbolized different sacred journeys.

The family and friends of the deceased had a choice of options that ranged in price for the preparation of the body, similar to the process at modern funeral homes.

[citation needed] The next step was to remove the internal organs, the lungs, liver, stomach, and intestines, and to place them in canopic jars with lids shaped as the heads of the protective deities, the four sons of Horus: Imsety, Hapy, Duamutef, and Qebhseneuf.

This was the time when the deceased turned into a semi divine being, and all that was left in the body from the first part was removed, followed by applying first wine and then oils.

[21] The cheapest, most basic method of mummification, which was often chosen by the poor, involved purging out the deceased's internal organs, and then laying the body in natron for 70 days.

The king's mummy was then placed inside the pyramid along with enormous amounts of food, drink, furniture, clothes, and jewelry that were to be used in the afterlife.

[33] Two hallmarks of the tomb included: a burial chamber, which housed the physical body of the deceased (inside a coffin) as well as funerary objects deemed most important, and a "cult place," which resembled a chapel where mourners, family, and friends could congregate.

They placed the body of the deceased in a tight position on its left side with a few jars of food and drink and slate palettes with magical religious spells alongside.

Ka, the vital force within the Ancient Egyptian concept of the soul, would not return to the deceased body if embalming was not carried out in the proper fashion.

Although the types of burial goods changed throughout ancient Egyptian history, their purpose to protect the deceased and provide sustenance in the afterlife remained.

For example, an anthropoid coffin shape became standardized and the deceased were provided with a small shabti statue, which the Egyptians believed would perform work for them in the afterlife.