Leopard skin (clothing in Ancient Egypt)

In the mortuary cult, the leopard skin is mentioned in the pyramid texts as a special symbol of protection and rule for the deceased king in connection with his ascension to heaven after the opening of the mouth ceremony.

The leopard skin is the king's symbol of power, with which he undertakes his daily journey through the celestial waters alongside the sun god.

In the Solar Sanctuary of Nyuserre (2455-2420 BC), a larger report is dedicated to the leopard in an appendix in connection with other birthing animals.

[6] An exact attribution to the cheetah or leopard is not possible, as it is only since the Middle Kingdom (2137-1781 BC) that the hieroglyph was no longer used for the word peh (lion or panther).

In the 5th Dynasty (2504-2347 BC), representations on royal temple reliefs of the Old Kingdom show in particular a linking of ancient Egyptian official titles to the leopard skin bearer; for example, the new priestly office of "Shem" is mentioned on the sed festival representations of Sahure in connection with the king's son as a leopard skin bearer.

In iconography, the sidelock of youth also served in the further course of ancient Egyptian history to identify primarily those royal descendants who were eligible as designated heirs to the throne.

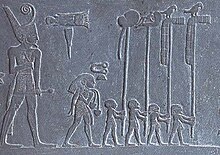

[12] A relief fragment from the area of the former temple of Hathor in Gebelein depicts the leopard skin bearer in the royal cult.

[13] Egyptologists interpret the actions of the leopard skin bearer as a foundation or hunting ritual and as a ceremony within the Sed festival.

The leopard skin bearer was active in the context of the Horus procession, in which the royal exercise of power as the maintenance of kingship was the dominant motif of the ceremonial acts.

[14] This connection is also shown in the festive scenes of the Pepi II pyramid, which is why it can be assumed that the office of the leopard skin bearer as Shem priest in the associated ceremonies was either occupied by the king's son or symbolically identified him as the acting person.

[12] In the Middle Kingdom, a torso made of granite for Amenemhet III documents the possibility that a designated king could also appear as a leopard skin bearer.

Amenemhet III can be seen on the granite block wearing a wispy wig and a strand of pearls in several rows, known as a "menat".

Wolfhart Westendorf emphasizes that the iconography of the Middle Kingdom corresponds to the traditional priestly dress of Tjet and shows Amenemhet III in the mythical phase of the divine Horus before he took the place of his father.

[15] In addition, Amenemhet III reveals the principle of the young Horus in Chemmis embodied by the deity Iunmutef.

Ramesses II is positioned behind Seti I in the associated depictions and, as the rightful heir, refers to the dynasty of kings who reigned before him, subtitled by name.

Therefore, they assumed the ritual execution of the necessary ceremonial acts in a reinterpretation of Sameref's earlier function as the bearer of the leopard skin.

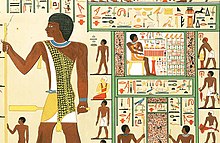

[16] As early as the Old Kingdom, the tomb owner is often depicted wearing a leopard skin cloak on false doors and the entrance areas of burial chambers.

It was also part of the standard equipment of those involved in the area of mortuary sacrifices; usually the eldest son or the Shem priests, who were elevated to the rank of sorcerer and thus received the status of "divinely endowed and recognized spirits of the dead".

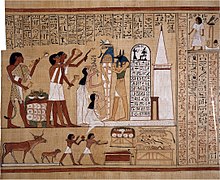

With the beginning of the New Kingdom, the depictions of the leopard skin predominate on account of its connection to the priestly cult of the dead as the "loving son" and "first of the sacrificial cortege".

In the opening of the mouth ceremony, however, the leopard skin retained its central effect as a cult object of the deceased.

[19] Unas was the first king (pharaoh) to have the underground pyramid chambers inscribed with reciting funerary texts in the form of "death sayings".

A wall painting depicts the opening of the mouth ceremony, in which Tutankhamun's successor Ay himself acts as leopard skin bearer and Shem priest.

In this depiction, the symbolic father-son relationship is clearly recognizable, in which Tutankhamun appears as the "loving son" of his "father" Amun.