Egyptian temple

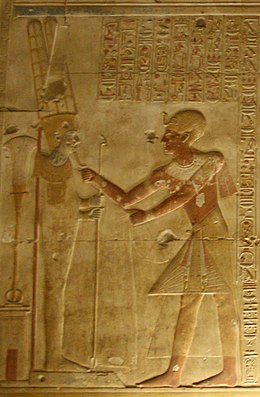

Pharaohs delegated most of their ritual duties to priests, but most of the populace was excluded from direct participation in ceremonies and forbidden to enter a temple's most sacred areas.

With the coming of Christianity, traditional Egyptian religion faced increasing persecution, and temple cults died out during the fourth through sixth centuries AD.

At the start of the nineteenth century, a wave of interest in ancient Egypt swept Europe, giving rise to the discipline of Egyptology and drawing increasing numbers of visitors to the civilization's remains.

[35] As the direct overseers of their own economic sphere, the administrations of large temples wielded considerable influence and may have posed a challenge to the authority of a weak pharaoh,[36] although it is unclear how independent they were.

[40] Despite the impermanence of these early buildings, later Egyptian art continually reused and adapted elements from them, evoking the ancient shrines to suggest the eternal nature of the gods and their dwelling places.

[41] In the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3100–2686 BC), the first pharaohs built funerary complexes in the religious center of Abydos following a single general pattern, with a rectangular mudbrick enclosure.

[54] The most important god of the time was Amun, whose main cult center, the Precinct of Amun-Re at Karnak in Thebes, eventually became the largest of all temples, and whose high priests may have wielded considerable political influence.

[55] Many temples were now built entirely of stone, and their general plan became fixed, with the sanctuary, halls, courtyards, and pylon gateways oriented along the path used for festival processions.

[53] As the wealth of the priesthoods continued to grow, so did their religious influence: temple oracles, controlled by the priests, were an increasingly popular method of making decisions.

[66] New architectural forms continued to develop, such as covered kiosks in front of gateways, more elaborate column styles, and the mammisi, a building celebrating the mythical birth of a god.

The last temple cults died out in the fourth through sixth centuries AD, although locals may have venerated some sites long after the regular ceremonies there had ceased.

[78][Note 3] Temples were built throughout Upper and Lower Egypt, as well as at Egyptian-controlled oases in the Libyan Desert as far west as Siwa, and at outposts in the Sinai Peninsula such as Timna.

[104] The typical parts of a temple, such as column-filled hypostyle halls, open peristyle courts, and towering entrance pylons, were arranged along this path in a traditional but flexible order.

The author argues that the ancient Egyptians embedded knowledge of sacred geometry and spiritual awakening into their architecture, and that the human body itself is a temple that mirrors the harmony of the universe.

Many temples, known as hypogea, were cut entirely into living rock, as at Abu Simbel, or had rock-cut inner chambers with masonry courtyards and pylons, as at Wadi es-Sebua.

[112] In many mortuary temples, the inner areas contained statues of the deceased pharaoh, or a false door where his ba ("personality") was believed to appear to receive offerings.

[122] The shadowy halls, whose columns were often shaped to imitate plants such as lotus or papyrus, were symbolic of the mythological marsh that surrounded the primeval mound at the time of creation.

[125] On occasion, this function was more than symbolic, especially during the last native dynasties in the fourth century BC, when the walls were fully fortified in case of invasion by the Achaemenid Empire.

Temple walls also frequently bear written or drawn graffiti, both in modern languages and in ancient ones such as Greek, Latin, and Demotic, the form of Egyptian that was commonly used in Greco-Roman times.

[151] Once the priesthood became more professional, the king seems to have used his power over appointments mainly for the highest-ranking positions, usually to reward a favorite official with a job or to intervene for political reasons in the affairs of an important cult.

[159] Prominent among these specialized roles was that of the lector priest who recited hymns and spells during temple rituals, and who hired out his magical services to laymen.

[160] Besides its priests, a large temple employed singers, musicians, and dancers to perform during rituals, plus the farmers, bakers, artisans, builders, and administrators who supplied and managed its practical needs.

[161] In the Ptolemaic era, temples could also house people who had sought asylum within the precinct, or recluses who voluntarily dedicated themselves to serving the god and living in its household.

They might, for instance, involve the destruction of models of inimical gods like Apep or Set, acts that were believed to have a real effect through the principle of ḥkꜣ (Egyptological pronunciation heka) "magic".

The motions of the barque as it was carried on the bearers' shoulders—making simple gestures to indicate "yes" or "no", tipping toward tablets on which possible answers were written, or moving toward a particular person in the crowd—were taken to indicate the god's reply.

[196] The evidence from those times indicates that while ordinary Egyptians used many venues to interact with the divine, such as household shrines or community chapels, the official temples with their sequestered gods were a major focus for popular veneration.

[198] More private areas for devotion were located at the building's outer wall, where large niches served as "chapels of the hearing ear" for individuals to speak to the god.

[201] Because the key rituals of any festival still took place within the temple, out of public sight, Egyptologist Anthony Spalinger has questioned whether the processions inspired genuine "religious feelings" or were simply seen as occasions for revelry.

[202] In any case, the oracular events during festivals provided an opportunity for people to receive responses from the normally isolated deities, as did the other varieties of oracle that developed late in Egyptian history.

[212] Nineteenth-century Egyptologists studied the temples intensively, but their emphasis was on the collection of artifacts to send to their own countries, and their slipshod excavation methods often did further harm.