Ancient Egyptian literature

This was a "media revolution" which, according to Richard B. Parkinson, was the result of the rise of an intellectual class of scribes, new cultural sensibilities about individuality, unprecedented levels of literacy, and mainstream access to written materials.

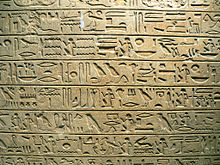

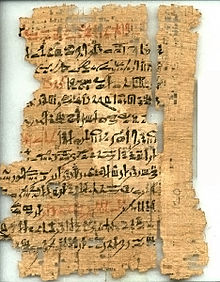

[15] Its primary purpose was to serve as a shorthand script for non-royal, non-monumental, and less formal writings such as private letters, legal documents, poems, tax records, medical texts, mathematical treatises, and instructional guides.

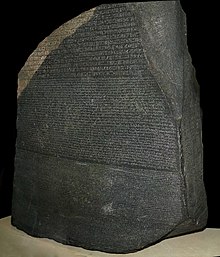

[18] Coptic became the standard in the 4th century AD when Christianity became the state religion throughout the Roman Empire; hieroglyphs were discarded as idolatrous images of a pagan tradition, unfit for writing the Biblical canon.

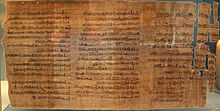

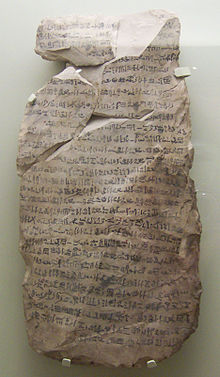

[19] With pigments of carbon black and red ochre, the reed pen was used to write on scrolls of papyrus—a thin material made from beating together strips of pith from the Cyperus papyrus plant—as well as on small ceramic or limestone potsherds known as ostraca.

[20] It is thought that papyrus rolls were moderately expensive commercial items, since many are palimpsests, manuscripts that have had their original contents erased or scraped off to make room for new written works.

[24] The adoption of Greco-Roman writing tools influenced Egyptian handwriting, as hieratic signs became more spaced, had rounder flourishes, and greater angular precision.

Stones with inscriptions were frequently re-used as building materials, and ceramic ostraca require a dry environment to ensure the preservation of the ink on their surfaces.

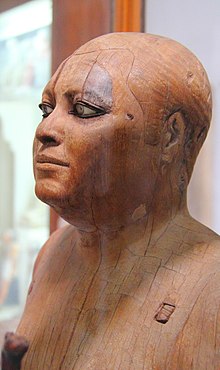

[40] Throughout ancient Egyptian history, the ability to read and write were the main requirements for serving in public office, although government officials were assisted in their day-to-day work by an elite, literate social group known as scribes.

[41] As evidenced by Papyrus Anastasi I of the Ramesside Period, scribes could even be expected, according to Wilson, "...to organize the excavation of a lake and the building of a brick ramp, to establish the number of men needed to transport an obelisk and to arrange the provisioning of a military mission".

[48] The privileged status of the scribe over illiterate manual laborers was the subject of a popular Ramesside Period instructional text, The Satire of the Trades, where lowly, undesirable occupations, for example, potter, fisherman, laundry man, and soldier, were mocked and the scribal profession praised.

[49] A similar demeaning attitude towards the illiterate is expressed in the Middle Kingdom Teaching of Khety, which is used to reinforce the scribes' elevated position within the social hierarchy.

[51] Classic works, such as the Story of Sinuhe and Instructions of Amenemhat, were copied by schoolboys as pedagogical exercises in writing and to instill the required ethical and moral values that distinguished the scribal social class.

Menena, a draughtsman working at Deir el-Medina during the Twentieth dynasty of Egypt, quoted passages from the Middle Kingdom narratives Eloquent Peasant and Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor in an instructional letter reprimanding his disobedient son.

[32] Menena's Ramesside contemporary Hori, the scribal author of the satirical letter in Papyrus Anastasi I, admonished his addressee for quoting the Instruction of Hardjedef in the unbecoming manner of a non-scribal, semi-educated person.

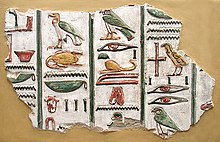

[64] Old Kingdom texts served mainly to maintain the divine cults, preserve souls in the afterlife, and document accounts for practical uses in daily life.

[84] These texts usually adopt the formulaic title structure of "the instruction of X made for Y", where "X" can be represented by an authoritative figure (such as a vizier or king) providing moral guidance to his son(s).

[109] The Middle Kingdom genre of "prophetic texts", also known as "laments", "discourses", "dialogues", and "apocalyptic literature",[110] include such works as the Admonitions of Ipuwer, Prophecy of Neferti, and Dispute between a man and his Ba.

[84] In Middle Kingdom texts, connecting themes include a pessimistic outlook, descriptions of social and religious change, and great disorder throughout the land, taking the form of a syntactic "then-now" verse formula.

[84] Although it survives only in later copies from the Eighteenth dynasty onward, Parkinson asserts that, due to obvious political content, Neferti was originally written during or shortly after the reign of Amenemhat I.

Neferti entertains the king with prophecies that the land will enter into a chaotic age, alluding to the First Intermediate Period, only to be restored to its former glory by a righteous king— Ameny—whom the ancient Egyptian would readily recognize as Amenemhat I.

[149] The educational text Book of Kemit, dated to the Eleventh dynasty, contains a list of epistolary greetings and a narrative with an ending in letter form and suitable terminology for use in commemorative biographies.

[72] During the late Middle Kingdom, greater standardization of the epistolary formula can be seen, for example in a series of model letters taken from dispatches sent to the Semna fortress of Nubia during the reign of Amenemhat III (r. 1860–1814 BC).

[155] Wente describes the versatility of this epistle, which contained "proper greetings with wishes for this life and the next, the rhetoric composition, interpretation of aphorisms in wisdom literature, application of mathematics to engineering problems and the calculation of supplies for an army, and the geography of western Asia".

[158] Olivier Perdu, a professor of Egyptology at the Collège de France, states that biographies did not exist in ancient Egypt, and that commemorative writing should be considered autobiographical.

[161] In her discussion of the Ecclesiastes of the Hebrew Bible, Jennifer Koosed, associate professor of religion at Albright College, explains that there is no solid consensus among scholars as to whether true biographies or autobiographies existed in the ancient world.

[171] The annals of Ramesses II (r. 1279–1213 BC), recounting the Battle of Kadesh against the Hittites include, for the first time in Egyptian literature, a narrative epic poem, distinguished from all earlier poetry that served to celebrate and instruct.

[175] For example, the Nubian pharaoh Piye (r. 752–721 BC), founder of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, had a stela erected and written in classical Middle Egyptian that describes with unusual nuances and vivid imagery his successful military campaigns.

[178] During the New Kingdom, scribes who traveled to ancient sites often left graffiti messages on the walls of sacred mortuary temples and pyramids, usually in commemoration of these structures.

[179] Modern scholars do not consider these scribes to have been mere tourists, but pilgrims visiting sacred sites where the extinct cult centers could be used for communicating with the gods.

[188] It was not until 1799, with the Napoleonic discovery of a trilingual (i.e. hieroglyphic, Demotic, Greek) stela inscription on the Rosetta Stone, that modern scholars had the resources to decipher Egyptian texts.