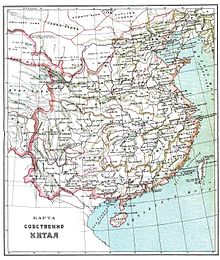

China proper

The term was first used by Westerners during the Manchu-led Qing dynasty to describe the distinction between the historical "Han lands" (漢地)—i.e.

[1] There is no fixed extent for China proper, as many administrative, cultural, and linguistic shifts have occurred in Chinese history.

There was no direct translation for "China proper" in the Chinese language at the time due to differences in terminology used by the Qing to refer to the regions.

Even to today, the expression is controversial among scholars, particularly in mainland China, due to issues pertaining to contemporary territorial claim and ethnic politics.

[citation needed] Outer China usually includes the geographical regions of Dzungaria, Tarim Basin, Gobi Desert,[note 2] Tibetan Plateau, and Manchuria.

However, it is plausible that historians during the age of empires and the fast-changing borders in the eighteenth century, applied it to distinguish the 18 provinces in China's interior from its frontier territories.

This would also apply to Great Britain proper versus the British Empire, which would encompass vast lands overseas.

[7][8][9] After conquering the Ming, the Qing identified their state as "China" (Zhongguo), and referred to it as "Dulimbai Gurun" in the Manchu language.

[10] When the Qing conquered Dzungaria in 1759, they proclaimed that the new land was absorbed into "China" (Dulimbai Gurun) in a Manchu language memorial.

[18] The Qing dynasty referred to the Han-inhabited 18 provinces as "nèidì shíbā shěng" (內地十八省), which meant the "interior region eighteen provinces", or abbreviated it as "nèidì" (內地), "interior region" and also as "jùnxiàn" (郡县), while they referred to the non-Han areas of China such as the Northeast, Outer Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Tibet as "wàifān" (外藩) which means "outer feudatories" or "outer vassals", or as "fānbù" (藩部, "feudatory region").

According to sinologist Colin Mackerras, foreign governments have generally accepted Chinese claims over its ethnic minority areas, because to redefine a country's territory every time it underwent a change of regime would cause endless instability and warfare.

It governed fifteen administrative entities, which included thirteen provinces (Chinese: 布政使司; pinyin: Bùzhèngshǐ Sī) and two "directly-governed" areas.

Near the end of the Qing dynasty, there was an effort to extend the province system of China proper to the rest of the empire.

Some revolutionaries, such as Zou Rong, used the term Zhongguo Benbu (中国本部) which roughly identifies the Eighteen Provinces.

[24] When the Qing dynasty fell, the abdication decree of the Xuantong Emperor bequeathed all the territories of the Qing dynasty to the new Republic of China, and the latter idea was therefore adopted by the new republic as the principle of Five Races Under One Union, with Five Races referring to the Han, Manchus, Mongols, Muslims (Uyghurs, Hui etc.)

Beijing and Tianjin were eventually split from Hebei (renamed from Zhili), Shanghai from Jiangsu, Chongqing from Sichuan, Ningxia autonomous region from Gansu, and Hainan from Guangdong.

When the Qing dynasty fell, Republican Chinese control of Qing territories, including of those generally considered to be in "China proper", was tenuous, and non-existent in Tibet and Mongolian People's Republic (former Outer Mongolia) since 1922, which were controlled by governments that declared independence from China.

Conversely, Han people form the majority in most of Manchuria, much of Inner Mongolia, many areas in Xinjiang and scattered parts of Tibet today, not least due to the expansion of Han settlement encouraged by the late Qing dynasty, the Republic of China, and the People's Republic of China.