El Tatio

El Tatio is a geothermal field with many geysers located in the Andes Mountains of northern Chile at 4,320 metres (14,170 ft) above mean sea level.

The vents are sites of populations of extremophile microorganisms such as hyperthermophiles, and El Tatio has been studied as an analogue for the early Earth and possible past life on Mars.

[d][28] Firn and snow fields were reported in the middle 20th century on the El Tatio volcanic group, at elevations of 4,900–5,200 metres (16,100–17,100 ft).

[7] The first area offers a notable contrast between the snow-covered Andes, the coloured hills that surround the field and the white deposits left by the geothermal activity.

[64] An additional geothermal system lies southeast of and at elevations above El Tatio and is characterized by steam-heated ponds fed by precipitation water,[11] and solfataric activity has been reported on the stratovolcanoes farther east.

[28] Deposition of sinter from the waters of the geothermal field has given rise to spectacular landforms, including, but not limited to mounds, terraced pools, geyser cones and the dams that form their rims.

The region was dominated by andesitic volcanism producing lava flows until the late Miocene, then large-scale ignimbrite activity took place between 10 and 1 million years ago.

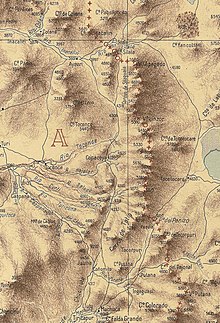

[95] The movement of the water in the ground is controlled by the permeability of the volcanic material and the Serrania de Tucle–Loma Lucero tectonic block west of El Tatio that acts as an obstacle.

Unlike geothermal fields in wetter parts of the world, given the dry climate of the area, local precipitation has little influence on the hot springs hydrology at El Tatio.

[68] Other compounds and elements in order of increasing concentration are antimony, rubidium, strontium, bromine, magnesium, caesium, lithium, arsenic, sulfate, boron, potassium and calcium.

[114] The decreasing chloride content on the other hand appears to be due to drainage coming from the east diluting the southern and western and especially eastern spring systems.

[121] Halite and other evaporites are more commonly encountered on the sinter surfaces outside of the hot springs,[122] and while opal dominates these environments too, sassolite and teruggite are found in addition to the aforementioned four minerals in the discharge deposits.

[125] Various facies have been identified in drill cores through the sinter, including arborescent, columnar, fenestral palisade, laminated (both inclined and planar), particulate, spicular and tufted structures.

[129] The region is additionally rather windy[130] with mean windspeeds of 3.7–7.5 metres per second (12–25 ft/s),[68] which influence the hot springs by enhancing evaporation[130] and imparting a directional growth to certain finger-like sinter deposits.

The low atmospheric pressure and high UV irradiation has led scientists to treat El Tatio as an analogue for environments on Mars.

[135] About 90 plant species have been identified at El Tatio and surroundings,[137] such as the endemic Adesmia atacamensis, Calceolaria stellariifolia, Junellia tridactyla and Opuntia conoidea.

[69] The vents are an extreme environment, given the presence of arsenic, the large amount of UV radiation that El Tatio receives[142] and its high elevation.

[103] Animal species found at El Tatio include the snail Heleobia,[166] the frog Rhinella spinulosa,[167] and water mites.

A related fault system was active; it is linked to Sol de Mañana in Bolivia[175] and controls the position of several vents in El Tatio.

The Rio Salado ignimbrite elsewhere crops out as two flow units, with varying colours, and close to El Tatio it is crystalline and densely welded.

[23] Petrological data suggest that over time the erupted lavas of the El Tatio volcanic group have become more mafic, with older products being andesitic and later ones basaltic-andesitic.

[201] Feasibility studies in northern Chile identified El Tatio as a potential site for geothermal power generation, with large-scale prospecting taking place in the 1960s and 1970s.

In 1973 and 1974, wells were drilled and it was estimated that if the geothermal resources were fully exploited, about 100–400 megawatts of electric power could be produced,[87] but the 1973 Chilean coup d'etat derailed further exploration efforts.

[87] A dispute over gas supplies for Northern Chile from Argentina in 2005 helped push the project forward,[204] and after an environmental impact review in 2007[205] the Chilean government in 2008 granted a concession to develop geothermal resources in the field, with the expected yield being about 100[142][206]-40 megawatt.

[207] On 8 September 2009,[208] an older well in El Tatio that was being reused blew out,[209] generating a 60-metre (200 ft) high steam fountain[208] that was not plugged until 4 October.

[211] The project had earlier been opposed by the local Atacameño population, owing to concerns about environmental damage[204] and the religious importance of water[212] and El Tatio in the region.

[225] An important factor in the Tatio controversy is the role of the tourism industry, which viewed the geothermal project as a threat; this kind of industry-industry conflict was unusual.

[226] While the incident ultimately did not result in lasting changes to the El Tatio geysers, the widespread media attention did create adverse publicity and social opposition - in particular among indigenous leaders in the region - against geothermal energy in Chile.

[17] Aside from viewing the geysers, bathing in the hot water, watching the natural scenery[230] and visiting surrounding Atacameño villages with their adobe buildings are other activities possible at El Tatio.

[237] In 2009, José Antonio Gómez Urrutia, then-senator of Chile for the Antofagasta region proposed that El Tatio be declared a natural sanctuary (a type of protected area); the corresponding parliamentary motion was approved in the same year.