History of physics

Aristotle (Greek: Ἀριστοτέλης, Aristotélēs) (384–322 BCE), a student of Plato, promoted the concept that observation of physical phenomena could ultimately lead to the discovery of the natural laws governing them.

[citation needed] Aristotle's writings cover physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology and zoology.

According to Aristotle, these four terrestrial elements are capable of inter-transformation and move toward their natural place, so a stone falls downward toward the center of the cosmos, but flames rise upward toward the circumference.

In contrast to Aristotle's geocentric views, Aristarchus of Samos (Greek: Ἀρίσταρχος; c. 310 – c. 230 BCE) presented an explicit argument for a heliocentric model of the Solar System, i.e. for placing the Sun, not the Earth, at its centre.

In mathematics, Archimedes used the method of exhaustion to calculate the area under the arc of a parabola with the summation of an infinite series, and gave a remarkably accurate approximation of pi.

Hipparchus (190–120 BCE), focusing on astronomy and mathematics, used sophisticated geometrical techniques to map the motion of the stars and planets, even predicting the times that Solar eclipses would happen.

A breakthrough in astronomy was made by Renaissance astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) when, in 1543, he gave strong arguments for the heliocentric model of the Solar System, ostensibly as a means to render tables charting planetary motion more accurate and to simplify their production.

The Greek astronomer Aristarchus of Samos (c. 310 – c. 230 BCE) had suggested that the Earth revolves around the Sun, but Copernicus's reasoning led to lasting general acceptance of this "revolutionary" idea.

[citation needed] Copernicus's new perspective, along with the accurate observations made by Tycho Brahe, enabled German astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) to formulate his laws regarding planetary motion that remain in use today.

The story in which Galileo is said to have dropped weights from the Leaning Tower of Pisa is apocryphal, but he did find that the path of a projectile is a parabola and is credited with conclusions that anticipated Newton's laws of motion (e.g. the notion of inertia).

At this time, intellectuals and scientists like René Descartes, Baruch Spinoza, Pierre Bayle, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, John Locke and Hugo Grotius resided in the Netherlands.

Newton's findings were set forth in his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica ("Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy"), the publication of which in 1687 marked the beginning of the modern period of mechanics and astronomy.

However, observed celestial motions did not precisely conform to a Newtonian treatment, and Newton, who was also deeply interested in theology, imagined that God intervened to ensure the continued stability of the solar system.

Beginning around 1700, a bitter rift opened between the Continental and British philosophical traditions, which were stoked by heated, ongoing, and viciously personal disputes between the followers of Newton and Leibniz concerning priority over the analytical techniques of calculus, which each had developed independently.

[57][58][59] Newton built the first functioning reflecting telescope[60] and developed a theory of color, published in Opticks, based on the observation that a prism decomposes white light into the many colours forming the visible spectrum.

Newton also formulated an empirical law of cooling, studied the speed of sound, investigated power series, demonstrated the generalised binomial theorem and developed a method for approximating the roots of a function.

But, already before the establishment of the ideal gas law, an associate of Boyle's named Denis Papin built in 1679 a bone digester, which is a closed vessel with a tightly fitting lid that confines steam until a high pressure is generated.

The statistical versus absolute interpretations of the second law of thermodynamics set up a dispute that would last for several decades (producing arguments such as "Maxwell's demon"), and that would not be held to be definitively resolved until the behavior of atoms was firmly established in the early 20th century.

So profound were these and other developments that it was generally accepted that all the important laws of physics had been discovered and that, henceforth, research would be concerned with clearing up minor problems and particularly with improvements of method and measurement.

Prominent physicists such as Hendrik Lorentz, Emil Cohn, Ernst Wiechert and Wilhelm Wien believed that some modification of Maxwell's equations might provide the basis for all physical laws.

One of these was the demonstration by Albert A. Michelson and Edward W. Morley – known as the Michelson–Morley experiment – which showed there did not seem to be a preferred frame of reference, at rest with respect to the hypothetical luminiferous ether, for describing electromagnetic phenomena.

Studies of radiation and radioactive decay continued to be a preeminent focus for physical and chemical research through the 1930s, when the discovery of nuclear fission by Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch opened the way to the practical exploitation of what came to be called "atomic" energy.

This aspect of relativity explained the phenomena of light bending around the sun, predicted black holes as well as properties of the Cosmic microwave background radiation – a discovery rendering fundamental anomalies in the classic Steady-State hypothesis.

The gradual acceptance of Einstein's theories of relativity and the quantized nature of light transmission, and of Niels Bohr's model of the atom created as many problems as they solved, leading to a full-scale effort to reestablish physics on new fundamental principles.

New principles of a "quantum" rather than a "classical" mechanics, formulated in matrix-form by Werner Heisenberg, Max Born, and Pascual Jordan in 1925, were based on the probabilistic relationship between discrete "states" and denied the possibility of causality.

Quantum mechanics was extensively developed by Heisenberg, Wolfgang Pauli, Paul Dirac, and Erwin Schrödinger, who established an equivalent theory based on waves in 1926; but Heisenberg's 1927 "uncertainty principle" (indicating the impossibility of precisely and simultaneously measuring position and momentum) and the "Copenhagen interpretation" of quantum mechanics (named after Bohr's home city) continued to deny the possibility of fundamental causality, though opponents such as Einstein would metaphorically assert that "God does not play dice with the universe".

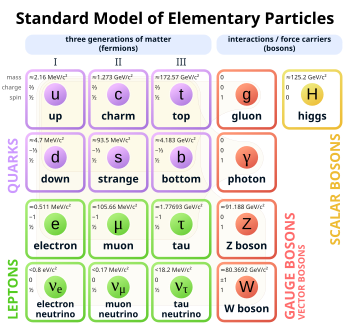

This situation was not considered adequately resolved until after World War II, when Julian Schwinger, Richard Feynman and Sin-Itiro Tomonaga independently posited the technique of renormalization, which allowed for an establishment of a robust quantum electrodynamics (QED).

Later work was by Smoot et al. (1989), among other contributors, using data from the Cosmic Background explorer (CoBE) and the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) satellites refined these observations.

In the 20th century, physics also became closely allied with such fields as electrical, aerospace and materials engineering, and physicists began to work in government and industrial laboratories as much as in academic settings.

Following World War II, the population of physicists increased dramatically, and came to be centered on the United States, while, in more recent decades, physics has become a more international pursuit than at any time in its previous history.

(1824–1907)

(1867–1934) was awarded two Nobel prizes, Physics (1903) and Chemistry (1911)