Physical oceanography

[1] Descriptive physical oceanography seeks to research the ocean through observations and complex numerical models, which describe the fluid motions as precisely as possible.

Dynamical physical oceanography focuses primarily upon the processes that govern the motion of fluids with emphasis upon theoretical research and numerical models.

GFD is a sub field of Fluid dynamics describing flows occurring on spatial and temporal scales that are greatly influenced by the Coriolis force.

[3][4] The tremendous heat capacity of the oceans moderates the planet's climate, and its absorption of various gases affects the composition of the atmosphere.

Surface temperatures can range from below freezing near the poles to 35 °C in restricted tropical seas, while salinity can vary from 10 to 41 ppt (1.0–4.1%).

In terms of temperature, the ocean's layers are highly latitude-dependent; the thermocline is pronounced in the tropics, but nonexistent in polar waters (Marshak 2001).

The halocline usually lies near the surface, where evaporation raises salinity in the tropics, or meltwater dilutes it in polar regions.

Salinity, a measure of the concentration of dissolved salts in seawater, typically ranges between 34 and 35 parts per thousand (ppt) in most of the world’s oceans.

However, localized factors such as evaporation, precipitation, river runoff, and ice formation or melting cause significant variations in salinity.

Understanding the complex interactions between temperature, salinity, and density is essential for predicting ocean circulation patterns, climate change effects, and the health of marine ecosystems.

These factors also influence marine life, as many species are sensitive to the specific temperature and salinity ranges of their habitats.

[8] The amount of sunlight absorbed at the surface varies strongly with latitude, being greater at the equator than at the poles, and this engenders fluid motion in both the atmosphere and ocean that acts to redistribute heat from the equator towards the poles, thereby reducing the temperature gradients that would exist in the absence of fluid motion.

In the southern hemisphere there is a continuous belt of ocean, and hence the mid-latitude westerlies force the strong Antarctic Circumpolar Current.

In the northern hemisphere the land masses prevent this and the ocean circulation is broken into smaller gyres in the Atlantic and Pacific basins.

In particular it means the flow goes around high and low pressure systems, permitting them to persist for long periods of time.

Langmuir circulation results in the occurrence of thin, visible stripes, called windrows on the surface of the ocean parallel to the direction that the wind is blowing.

These windrows are created by adjacent ovular water cells (extending to about 6 m (20 ft) deep) alternating rotating clockwise and counterclockwise.

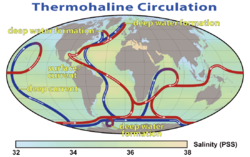

The interaction of ocean circulation, which serves as a type of heat pump, and biological effects such as the concentration of carbon dioxide can result in global climate changes on a time scale of decades.

Since it is a wave-2 phenomenon (there are two peaks and two troughs in a latitude circle) at each fixed point in space a signal with a period of four years is seen.

It interconnects the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans, and provide an uninterrupted stretch for the prevailing westerly winds to significantly increase wave amplitudes.

It is analogous to the Gulf Stream in the Atlantic Ocean, transporting warm, tropical water northward towards the polar region.

For example, the majority of the warm water movement in the south Atlantic is thought to have originated in the Indian Ocean.

[10] Another example of advection is the nonequatorial Pacific heating which results from subsurface processes related to atmospheric anticlines.

[12] The international awareness of global warming has focused scientific research on this topic since the 1988 creation of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Improved ocean observation, instrumentation, theory, and funding has increased scientific reporting on regional and global issues related to heat.

The tides produced by these two bodies are roughly comparable in magnitude, but the orbital motion of the Moon results in tidal patterns that vary over the course of a month.

Incoming tides can also produce a tidal bore along a river or narrow bay as the water flow against the current results in a wave on the surface.

Tide and Current (Wyban 1992) clearly illustrates the impact of these natural cycles on the lifestyle and livelihood of Native Hawaiians tending coastal fishponds.

The primary impact of these waves is along the coastal shoreline, as large amounts of ocean water are cyclically propelled inland and then drawn out to sea.

[15] The wind generates ocean surface waves, which have a large impact on offshore structures, ships, Coastal erosion and sedimentation, as well as harbours.