Electron-beam welding

EBW provides excellent welding conditions because it involves: Beam effectiveness depends on many factors.

The most important are the physical properties of the materials to be welded, especially the ease with which they can be melted or vaporize under low-pressure conditions.

At lower values of surface power density (in the range of about 103 W/mm2) the loss of material by evaporation is negligible for most metals, which is favorable for welding.

Conduction electrons (those not bound to the nucleus of atoms) move in a crystal lattice of metals with velocities distributed according to Gauss's law and depending on temperature.

Tungsten cathodes allow emission current densities about 100 mA/mm2, but only a small portion of the emitted electrons takes part in beam formation, depending on the electric field produced by the anode and control electrode voltages.

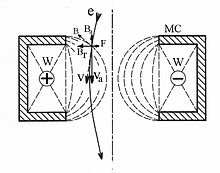

The most frequently used cathode is made of a tungsten strip, about 0.05 mm thick, shaped as shown in Figure 1a.

This can be achieved by an electric field in the proximity of the cathode which has a radial addition and an axial component, forcing the electrons in the direction of the axis.

At least this part of electron gun must be evacuated to high vacuum, to prevent "burning" the cathode and the emergence of electrical discharges.

After leaving the anode, the divergent electron beam does not have a power density sufficient for welding metals and has to be focused.

This effect is a force proportional to the induction B of the field and electron velocity v. The vector product of the radial component of induction Br and axial component of velocity va is a force perpendicular to those vectors, causing the electron to move around the axis.

In this context variations of focal length (exciting current) cause a slight rotation of the beam cross-section.

This is commonly accomplished mechanically by moving the workpiece with respect to the electron gun, but sometimes it is preferable to deflect the beam instead.

Because electrons transfer their energy into heat in a thin layer of the solid, the power density in this volume can be high.

This technology cannot be applied to materials with high vapour pressure at the melting temperature, which affects zinc, cadmium, magnesium, and practically all non-metals.

[2] Some metal components cannot be welded, i.e. to melt part of both in the vicinity of the joint, if the materials have different properties.

The advantage of electron-beam welding is its ability to localize heating to a precise point and to control exactly the energy needed for the process.

A general rule for construction of joints made this way is that the part with the lower melting point should be directly accessible by the beam.

If the material melted by the beam shrinks during cooling after solidification, cracking, deformation and changes of shape may occur.

Many welder types have been designed, differing in construction, working space volume, workpiece manipulators, and beam power.

Electron-beam generators (electron guns) designed for welding applications can supply beams with power ranging from a few watts up to some one hundred kilowatts.

Its negative potential controls the portion of emitted electrons entering into the accelerating field, i.e., the electron-beam current.

This can be done by applying a magnetic field of some specific radial direction and strength perpendicular to the optical axis before the focusing lens.

Electronics control the workpiece manipulator, monitor the welding process, and adjust the various voltages needed for a specific application.