Somite

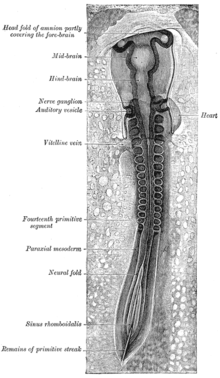

In vertebrates, somites subdivide into the dermatomes, myotomes, sclerotomes and syndetomes that give rise to the vertebrae of the vertebral column, rib cage, part of the occipital bone, skeletal muscle, cartilage, tendons, and skin (of the back).

In this definition, the somite is a homologously-paired structure in an animal body plan, such as is visible in annelids and arthropods.

Additionally, they retain the ability to become any kind of somite-derived structure until relatively late in the process of somitogenesis.

The number of somites is species dependent and independent of embryo size (for example, if modified via surgery or genetic engineering).

[4][8] As cells within the paraxial mesoderm begin to come together, they are termed somitomeres, indicating a lack of complete separation between segments.

The Notch system, as part of the clock and wavefront model, forms the boundaries of the somites.

The Hox genes specify somites as a whole based on their position along the anterior-posterior axis through specifying the pre-somitic mesoderm before somitogenesis occurs.

In the developing vertebrate embryo, somites split to form dermatomes, skeletal muscle (myotomes), tendons and cartilage (syndetomes)[9] and bone (sclerotomes).

[10] The dermatome is the dorsal portion of the paraxial mesoderm somite which gives rise to the skin (dermis).

[2] The myoblasts from the hypaxial division form the muscles of the thoracic and anterior abdominal walls.

In fishes, salamanders, caecilians, and reptiles, the body musculature remains segmented as in the embryo, though it often becomes folded and overlapping, with epaxial and hypaxial masses divided into several distinct muscle groups.

In addition, the somites specify the migration paths of neural crest cells and the axons of spinal nerves.

Other cells move distally to the costal processes of thoracic vertebrae to form the ribs.