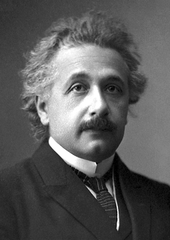

Albert Einstein

[9] On the eve of World War II, he endorsed a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt alerting him to the potential German nuclear weapons program and recommending that the US begin similar research.

He began teaching himself algebra, calculus and Euclidean geometry when he was twelve; he made such rapid progress that he discovered an original proof of the Pythagorean theorem before his thirteenth birthday.

He arrived at his revolutionary ideas about space, time and light through thought experiments about the transmission of signals and the synchronization of clocks, matters which also figured in some of the inventions submitted to him for assessment.

[73] Einstein's first paper, "Folgerungen aus den Capillaritätserscheinungen" ("Conclusions drawn from the phenomena of capillarity"), in which he proposed a model of intermolecular attraction that he afterwards disavowed as worthless, was published in the journal Annalen der Physik in 1901.

Titled "Eine neue Bestimmung der Moleküldimensionen" ("A New Determination of Molecular Dimensions") and dedicated to his friend Marcel Grossman, it was completed on 30 April 1905[76] and approved by Professor Alfred Kleiner of the University of Zurich three months later.

[80] Promotion to a full professorship followed in April 1911, when he accepted a chair at the German Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague, a move which required him to become an Austrian citizen of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was not completed.

[83] They offered him membership of the Prussian Academy of Sciences, the directorship of the planned Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics and a chair at the Humboldt University of Berlin that would allow him to pursue his research supported by a professorial salary but with no teaching duties to burden him.

[7] At this point some physicists still regarded the general theory of relativity skeptically, and the Nobel citation displayed a degree of doubt even about the work on photoelectricity that it acknowledged: it did not assent to Einstein's notion of the particulate nature of light, which only won over the entire scientific community when S. N. Bose derived the Planck spectrum in 1924.

[45][93] A total eclipse of the Sun that took place on 29 May 1919 provided an opportunity to put his theory of gravitational lensing to the test, and observations performed by Sir Arthur Eddington yielded results that were consistent with his calculations.

[94] With Eddington's eclipse observations widely reported not just in academic journals but by the popular press as well, Einstein became perhaps the world's first celebrity scientist, a genius who had shattered a paradigm that had been basic to physicists' understanding of the universe since the seventeenth century.

[102][103]) He was greeted with even greater enthusiasm on the last leg of his tour, in which he spent twelve days in Mandatory Palestine, newly entrusted to British rule by the League of Nations in the aftermath of the First World War.

By persuading Secretary General Eric Drummond to deny Einstein the place on the committee reserved for a Swiss thinker, they created an opening for Gonzague de Reynold, who used his League of Nations position as a platform from which to promote traditional Catholic doctrine.

[110] Their tour was suggested by Jorge Duclout (1856–1927) and Mauricio Nirenstein (1877–1935)[111] with the support of several Argentine scholars, including Julio Rey Pastor, Jakob Laub, and Leopoldo Lugones.

and was financed primarily by the Council of the University of Buenos Aires and the Asociación Hebraica Argentina (Argentine Hebraic Association) with a smaller contribution from the Argentine-Germanic Cultural Institution.

Caltech supported him in his wish that he should not be exposed to quite as much attention from the media as he had experienced when visiting the US in 1921, and he therefore declined all the invitations to receive prizes or make speeches that his admirers poured down upon him.

During the days following, he was given the keys to the city by Mayor Jimmy Walker and met Nicholas Murray Butler, the president of Columbia University, who described Einstein as "the ruling monarch of the mind".

[122] Historian Gerald Holton describes how, with virtually no audible protest being raised by their colleagues, thousands of Jewish scientists were suddenly forced to give up their university positions and their names were removed from the rolls of institutions where they were employed.

[133] Einstein later contacted leaders of other nations, including Turkey's Prime Minister, İsmet İnönü, to whom he wrote in September 1933, requesting placement of unemployed German-Jewish scientists.

[135] On 3 October 1933, Einstein delivered a speech on the importance of academic freedom before a packed audience at the Royal Albert Hall in London, with The Times reporting he was wildly cheered throughout.

Einstein and Szilárd, along with other refugees such as Edward Teller and Eugene Wigner, regarded it as their responsibility to alert Americans to the possibility that German scientists might win the race to build an atomic bomb, and to warn that Hitler would be more than willing to resort to such a weapon.

Some say that as a result of Einstein's letter and his meetings with Roosevelt, the US entered the "race" to develop the bomb, drawing on its "immense material, financial, and scientific resources" to initiate the Manhattan Project.

[190] In a German-language letter to philosopher Eric Gutkind, dated 3 January 1954, Einstein wrote: The word God is for me nothing more than the expression and product of human weaknesses, the Bible a collection of honorable, but still primitive legends which are nevertheless pretty childish.

General relativity has developed into an essential tool in modern astrophysics; it provides the foundation for the current understanding of black holes, regions of space where gravitational attraction is so strong that not even light can escape.

The existence of gravitational waves is possible under general relativity due to its Lorentz invariance which brings the concept of a finite speed of propagation of the physical interactions of gravity with it.

[255] In late 2013, a team led by the Irish physicist Cormac O'Raifeartaigh discovered evidence that, shortly after learning of Hubble's observations of the recession of the galaxies, Einstein considered a steady-state model of the universe.

[258][259] As he stated in the paper, In what follows, I would like to draw attention to a solution to equation (1) that can account for Hubbel's [sic] facts, and in which the density is constant over time [...] If one considers a physically bounded volume, particles of matter will be continually leaving it.

Because these solutions included spacetime curvature without the presence of a physical body, Einstein and Rosen suggested that they could provide the beginnings of a theory that avoided the notion of point particles.

[273] In 1924, Einstein received a description of a statistical model from Indian physicist Satyendra Nath Bose, based on a counting method that assumed that light could be understood as a gas of indistinguishable particles.

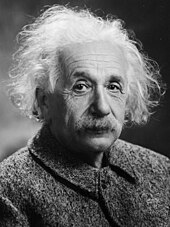

[295] His attempt to find the most fundamental laws of nature won him praise but not success: a particularly conspicuous blemish of his model was that it did not accommodate the strong and weak nuclear forces, neither of which was well understood until many years after his death.

In the period before World War II, The New Yorker published a vignette in their "The Talk of the Town" feature saying that Einstein was so well known in America that he would be stopped on the street by people wanting him to explain "that theory".

Ladies (coughs) and gentlemen, our age is proud of the progress it has made in man's intellectual development. The search and striving for truth and knowledge is one of the highest of man's qualities ...