Nerva

Nerva's greatest success was ensuring a peaceful transition of power after his death by selecting Trajan as his heir, thus founding the Nerva–Antonine dynasty.

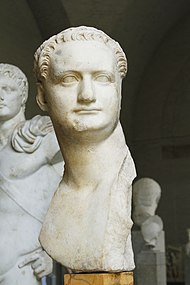

[2] Like Vespasian, the founder of the Flavian dynasty, Nerva was a member of a newer Italian nobility and plebian, rather than one of the patrician Julio-Claudians.

[5] Nevertheless, the Cocceii were among the most esteemed and prominent political families of the late Republic and early Empire, attaining consulships in each successive generation.

The Cocceii were connected with the Julio-Claudian dynasty through the marriage of Sergia Plautilla's brother Gaius Octavius Laenas, and Rubellia Bassa, the great-granddaughter of Tiberius.

His exact contribution to the investigation is not known, but his services must have been considerable, since they earned him rewards equal to those of Nero's guard prefect Tigellinus.

[2] According to the contemporary poet Martial, Nero also held Nerva's literary abilities in high esteem, hailing him as the "Tibullus of our time".

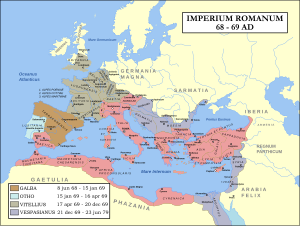

[9] After 71 Nerva again disappears from historical record, presumably continuing his career as an inconspicuous advisor under Vespasian (69–79) and his sons Titus (79–81) and Domitian (81–96).

[10] The governor of Germania Inferior, Lappius Maximus, moved to the region at once, assisted by the procurator of Rhaetia, Titus Flavius Norbanus.

[12] The Fasti Ostienses, the Ostian Calendar, records that the same day the Senate proclaimed Marcus Cocceius Nerva emperor.

Considering the works of Suetonius were published under Nerva's direct descendants Trajan and Hadrian, it would have been less than sensitive of him to suggest the dynasty owed its accession to murder.

[17] On the other hand, Nerva lacked widespread support in the Empire, and as a known Flavian loyalist his track record would not have recommended him to the conspirators.

The precise facts have been obscured by history,[19] but modern historians believe Nerva was proclaimed Emperor solely on the initiative of the Senate, within hours after the news of the assassination broke.

Nerva had seen the anarchy which had resulted from the death of Nero; he knew that to hesitate even for a few hours could lead to violent civil conflict.

[22] Following the accession of Nerva as emperor, the Senate passed damnatio memoriae on Domitian: his statues were melted, his arches were torn down and his name was erased from all public records.

As an immediate gesture of goodwill towards his supporters, Nerva publicly swore that no senators would be put to death as long as he remained in office.

[28][29] Since Suetonius says the people were ambivalent at Domitian's death, Nerva had to introduce a number of measures to gain support among the Roman populace.

[34] The most superfluous religious sacrifices, games and horse races were abolished, while new income was generated from Domitian's former possessions, including the auctioning of ships, estates, and even furniture.

[27] Large amounts of money were obtained from Domitian's silver and gold statues, and Nerva forbade that similar images be made in his honor.

The latter program was headed by the former consul Sextus Julius Frontinus, who helped to put an end to abuses and later published a significant work on Rome's water supply, De aquaeductu.

[23] In an attempt to appease the soldiers of the Praetorian Guard, Nerva had dismissed their prefect Titus Petronius Secundus – one of the chief conspirators against Domitian – and replaced him with a former commander, Casperius Aelianus.

[38] Likewise, the generous donativum bestowed upon the soldiers following his accession was expected to swiftly silence any protests against the violent regime change.

While the rapid transfer of power following Domitian's death had prevented a civil war from erupting, Nerva's position as emperor soon proved too vulnerable, and his benign nature turned into a reluctance to assert his authority.

This measure led to chaos, as everyone acted in his own interests while trying to settle scores with personal enemies, leading the consul Fronto to famously remark that Domitian's tyranny was ultimately preferable to Nerva's anarchy.

[43] In October 97, these tensions came to a head when the Praetorian Guard, led by Casperius Aelianus, laid siege to the Imperial Palace and took Nerva hostage.

[29] He was forced to submit to their demands, agreeing to hand over those responsible for Domitian's death and even giving a speech thanking the rebellious Praetorians.

But Nerva did not esteem family relationship above the safety of the State, nor was he less inclined to adopt Trajan because the latter was a Spaniard instead of an Italian or Italot, inasmuch as no foreigner had previously held the Roman sovereignty; for he believed in looking at a man's ability rather than at his nationality.

Edward Gibbon's famous assertion that Nerva hereby established a tradition of succession through adoption among the Five Good Emperors has found little support among some modern historians.

Gibbon considered Nerva the first of the Five Good Emperors, five successive rulers under whom the Roman Empire "was governed by absolute power, under the guidance of wisdom and virtue" from 96 until 180.

His mild disposition was respected by the good; but the degenerate Romans required a more vigorous character, whose justice should strike terror into the guilty.

The Roman Senate enjoyed renewed liberties under his rule, but Nerva's mismanagement of the state finances and lack of authority over the army ultimately brought Rome near the edge of a significant crisis.