England in the High Middle Ages

Childless and embroiled in conflict with the formidable Godwin, Earl of Wessex, and his sons, Edward may also have encouraged Duke William of Normandy's ambitions for the English throne.

[25] England's growing wealth was critical in allowing the Norman kings to project power across the region, including funding campaigns along the frontiers of Normandy.

This plan was later abandoned, but William continued to pursue a ferociously warlike defence of his French possessions and interests, exemplified by his response to the attempt by Elias de la Flèche, Count of Maine, to take Le Mans in 1099.

Henry's control of Normandy was challenged by Louis VI of France, Baldwin of Flanders and Fulk of Anjou, who promoted the rival claims of Robert's son, William Clito, and supported a major rebellion in the Duchy between 1116 and 1119.

[42] After Stephen's death in 1154 Henry succeeded as the first Angevin king of England, so-called because he was also the Count of Anjou in Northern France, adding it to his extensive holdings in Normandy and Aquitaine.

[53] However, the Treaty of Windsor in 1175, under which Rory O'Connor would be recognised as the High King of Ireland, giving homage to Henry and maintaining stability on the ground on his behalf,[54] meant that he had little direct control.

On hearing the news Henry uttered the infamous phrase "what miserable drones and traitors have I nurtured and promoted in my household who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low born clerk".

He had rejected and humiliated the king of France's sister; insulted and refused spoils of the Third Crusade to nobles like Leopold V, Duke of Austria, and was rumoured to have arranged the assassination of Conrad of Montferrat.

Custody was passed to Henry the Lion and a tax of 25 per cent of movables and income was required in England to pay the ransom of 100,000 marks, with a promise of 50,000 more, before Richard was released in 1194.

Yet again Philip II of France took the opportunity to destabilise the Plantagenet territories on the European mainland, supporting his vassal Arthur's claim to the English crown.

This is considered by some historians to mark the end of the Angevin period and the beginning of the Plantagenet dynasty with John's death and William Marshall's appointment as the protector of the nine-year-old Henry III.

[90] Successive kings still needed more resources to pay for military campaigns, conduct building programmes, or to reward their followers, and this meant exercising their feudal rights to interfere in the land-holdings of nobles.

[92] Property and wealth became increasingly focused in the hands of a subset of the nobility, the great magnates, at the expense of the wider baronage, encouraging the breakdown of some aspects of local feudalism.

[97] Significant gender inequities persisted throughout the period, as women typically had more limited life-choices, access to employment and trade, and legal rights than men.

Married or widowed noblewomen remained significant cultural and religious patrons and played an important part in political and military events, even if chroniclers were uncertain if this was appropriate behaviour.

[113] England's bishops remained powerful temporal figures, and in the early twelfth-century raised armies against Scottish invaders and built up extensive holdings of castles across the country.

[117] The religious military orders that became popular across Europe from the twelfth century onwards, including the Templars, Teutonic Knights and Hospitallers, acquired possessions in England.

[119] William promoted celibacy amongst the clergy and gave ecclesiastical courts more power, but also reduced the Church's direct links to Rome and made it more accountable to the king.

[121] Despite the bishops continuing to play a major part in royal government, tensions emerged between the kings of England and key leaders within the English Church.

[126] Under the Normans, religious institutions with important shrines, such as Glastonbury, Canterbury and Winchester, promoted themselves as pilgrimage destinations, maximising the value of the historic miracles associated with the sites.

[141] The English economy was fundamentally agricultural, depending on growing crops such as wheat, barley and oats on an open field system, and husbanding sheep, cattle and pigs.

[145] Although the Norman invasion caused some damage as soldiers looted the countryside and land was confiscated for castle building, the English economy was not greatly affected.

[149] Many hundreds of new towns, some of them planned communities, were built across England, supporting the creation of guilds, charter fairs and other medieval institutions which governed the growing trade.

[150] Jewish financiers played a significant role in funding the growing economy, along with the new Cistercian and Augustinian religious orders that emerged as major players in the wool trade of the north.

[152] Anglo-Norman warfare was characterised by attritional military campaigns, in which commanders tried to raid enemy lands and seize castles in order to allow them to take control of their adversaries' territory, ultimately winning slow but strategic victories.

[154] At the heart of these armies was the familia regis, the permanent military household of the king, which was supported in war by feudal levies, drawn up by local nobles for a limited period of service during a campaign.

[156] Naval forces played an important role during the Middle Ages, enabling the transportation of troops and supplies, raids into hostile territory and attacks on enemy fleets.

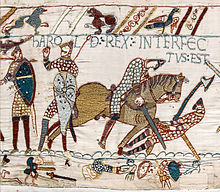

[163] In other artistic areas, including embroidery, the Anglo-Saxon influence remained evident into the twelfth century, and the famous Bayeux Tapestry is an example of older styles being reemployed under the new regime.

[176] Walter Scott's location of Robin Hood in the reign of Richard I and his emphasis on the conflict between Saxons and Normans set the template for much later fiction and film adaptations.

[179] Film-makers have drawn extensively on the medieval period, often taking themes from Shakespeare or the Robin Hood ballads for inspiration and adapting historical romantic novels as Ivanhoe (1952).