English Civil War

Parliament's strengths spanned the industrial centres, ports, and economically advanced regions of southern and eastern England, including the remaining cathedral cities (except York, Chester, Worcester).

By the 17th century, Parliament's tax-raising powers had come to be derived from the fact that the gentry was the only stratum of society with the ability and authority to collect and remit the most meaningful forms of taxation then available at the local level.

From the thirteenth century, monarchs ordered the election of representatives to sit in the House of Commons, with most voters being the owners of property, although in some potwalloper boroughs every male householder could vote.

He believed in High Anglicanism, a sacramental version of the Church of England, theologically based upon Arminianism, a creed shared with his main political adviser, Archbishop William Laud.

In 1637, John Bastwick, Henry Burton, and William Prynne had their ears cut off for writing pamphlets attacking Laud's views – a rare penalty for gentlemen, and one that aroused anger.

Henry Vane the Younger supplied evidence of Strafford's claimed improper use of the army in Ireland, alleging that he had encouraged the King to use his Ireland-raised forces to threaten England into compliance.

[44] These notes contained evidence that Strafford had told the King, "Sir, you have done your duty, and your subjects have failed in theirs; and therefore you are absolved from the rules of government, and may supply yourself by extraordinary ways; you have an army in Ireland, with which you may reduce the kingdom.

[62] In early January 1642, a few days after failing to capture five members of the House of Commons, Charles feared for the safety of his family and retinue and left the London area for the north country.

[67][68] At the outset of the conflict, much of the country remained neutral, though the Royal Navy and most English cities favoured Parliament, while the King found marked support in rural communities.

On the other, most Parliamentarians initially took up arms to defend what they viewed as a traditional balance of government in church and state, and which they felt had been undermined by bad advice the King received from his advisers — such as George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham — and during his Personal Rule (the "Eleven Years' Tyranny").

[70] At the time, Charles had with him about 2,000 cavalry and a small number of Yorkshire infantrymen, and using the archaic system of a Commission of Array,[71] his supporters started to build a larger army around the standard.

The Council decided on the London route, but not to avoid a battle, for the Royalist generals wanted to fight Essex before he grew too strong, and the temper of both sides made it impossible to postpone the decision.

The turning point came in the late summer and early autumn of 1643, when the Earl of Essex's army forced the king to raise the Siege of Gloucester[92] and then brushed the Royalists aside at the First Battle of Newbury (20 September 1643),[93] to return triumphantly to London.

Political manoeuvring to gain an advantage in numbers led Charles to negotiate a ceasefire in Ireland, freeing up English troops to fight on the Royalist side in England,[96] while Parliament offered concessions to the Scots in return for aid and assistance.

Forces loyal to Parliament[109] put down most of those in England after little more than a skirmish, but uprisings in Kent, Essex and Cumberland, the rebellion in Wales, and the Scottish invasion involved pitched battles and prolonged sieges.

Fairfax, after his success at Maidstone and the pacification of Kent, turned north to reduce Essex, where, under an ardent, experienced and popular leader, Sir Charles Lucas, the Royalists had taken up arms in great numbers.

[116] Of five prominent Royalist peers who had fallen into Parliamentary hands, three – the Duke of Hamilton, the Earl of Holland, and Lord Capel, one of the Colchester prisoners and a man of high character – were beheaded at Westminster on 9 March.

[127] The joint Royalist and Confederate forces under the Duke of Ormonde tried to eliminate the Parliamentary army holding Dublin by laying siege in 1649, but their opponents routed them at the Battle of Rathmines (2 August 1649).

[128] Admiral Robert Blake, a former Member of Parliament, had blockaded Prince Rupert's fleet in Kinsale, enabling Oliver Cromwell to land at Dublin on 15 August 1649 with an army to quell the Royalist alliance.

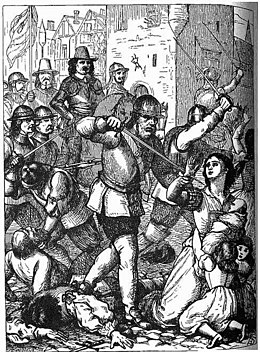

After the Siege of Drogheda,[129] the massacre of nearly 3,500 people – around 2,700 Royalist soldiers and 700 others, including civilians, prisoners, and Catholic priests (all of whom Cromwell claimed had carried arms) – became one of the historical memories that has driven Irish-English and Catholic-Protestant strife during the last three centuries.

[130] In the wake of the conquest, the victors confiscated almost all Irish Catholic-owned land and distributed it to Parliament's creditors, to Parliamentary soldiers who served in Ireland, and to English who had settled there before the war.

[138] The next year, 1652, saw a mopping up of the remnants of Royalist resistance, and under the terms of the "Tender of Union", the Scots received 30 seats in a united Parliament in London, with General Monck as the military governor of Scotland.

[146][147] In addition, Wales comparatively more rural in character than England at this time, and thereby lacking the large number of urban settlements home to mercantile, trade, and manufacturing interests who were a bulwark of support for both Puritanism and eventually the Parliamentarian cause.

The Martin Marprelate tracts (1588–1589), applying the pejorative name of prelacy to the church hierarchy, attacked the office of bishop with satire that deeply offended Elizabeth I and her Archbishop of Canterbury John Whitgift.

Parliament passed An Act for prohibiting Trade with the Barbadoes, Virginia, Bermuda and Antego in October 1650, which stated that: ...due punishment [be] inflicted upon the said Delinquents, do Declare all and every the said persons in Barbada's, Antego, Bermuda's and Virginia, that have contrived, abetted, aided or assisted those horrid Rebellions, or have since willingly joyned with them, to be notorious Robbers and Traitors, and such as by the Law of Nations are not to be permitted any manner of Commerce or Traffic with any people whatsoever; and do forbid to all manner of persons, Foreigners, and others, all manner of Commerce, Traffic and Correspondence whatsoever, to be used or held with the said Rebels in the Barbados, Bermuda's, Virginia and Antego, or either of them.The Act also authorised Parliamentary privateers to act against English vessels trading with the rebellious colonies: All Ships that Trade with the Rebels may be surprized.

[167] Although Petty's figures are the best available, they are still acknowledged as tentative; they do not include an estimated 40,000 driven into exile, some of whom served as soldiers in European continental armies, while others were sold as indentured servants to New England and the West Indies.

[186] The outcome of this system was that the future Kingdom of Great Britain, formed in 1707 under the Acts of Union, managed to forestall the kind of revolution typical of European republican movements which generally resulted in total abolition of their monarchies.

The major Whig historian, S. R. Gardiner, popularised the idea that the English Civil War was a "Puritan Revolution"[193] that challenged the repressive Stuart Church and prepared the way for religious toleration.

For example, Charles finally made terms with the Covenanters in August 1641, but although this might have weakened the position of the English Parliament, the Irish Rebellion of 1641 broke out in October 1641, largely negating the political advantage he had obtained by relieving himself of the cost of the Scottish invasion.

[200] Glen Burgess (1998) examined political propaganda written by the Parliamentarian politicians and clerics at the time, noting that many were or may have been motivated by their Puritan religious beliefs to support the war against the 'Catholic' king Charles I, but tried to express and legitimise their opposition and rebellion in terms of a legal revolt against a monarch who had violated crucial constitutional principles and thus had to be overthrown.

Lord Protector in 1653