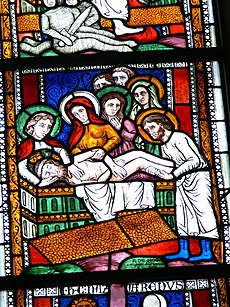

Burial of Jesus

Writing to the Corinthians around the year AD 54,[4] he refers to the account he had received of the death and resurrection of Jesus ("and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures").

[7] The Jewish historian Josephus, writing later in the century, described how the Jews regarded this law as so important that even the bodies of crucified criminals would be taken down and buried before sunset.

[11] In this account, Joseph does only the bare minimum to observe the Law, wrapping the body in a cloth, with no mention of washing (Taharah) or anointing it.

[15][16] Many interpreters have read this as a subtle orientation by the author towards wealthy supporters,[16] while others believe this is a fulfillment of prophecy from Isaiah 53:9: "And they made his grave with the wicked, And with the rich his tomb; Although he had done no violence, Neither was any deceit in his mouth."

An argument in favor of a decent burial before sunset is the Jewish custom, based on the Torah, that the body of an executed person should not remain on the tree where the corpse was hung for public display, but be buried before sunrise.

[29][30] Martin Hengel argued that Jesus was buried in disgrace as an executed criminal who died a shameful death,[31][32] a view which is "now widely accepted and has become entrenched in scholarly literature.

[35] What really happened may be deduced from customary Roman practice, which was to leave the body on the stake, denying a honorable or family burial, famously stating that "the dogs were waiting.

"[36][37][note 3] British New Testament scholar Maurice Casey also notes that "Jewish criminals were supposed to receive a shameful and dishonourable burial",[38] quoting Josephus: The general situation was sufficient for Josephus to comment on the end of a biblical thief, 'And after being immediately put to death, he was given at night the dishonourable burial proper to the condemned' (Jos.

"[42] Referring to Hengel and Crossan, Ehrman argues that crucifixion was meant "to torture and humiliate a person as fully as possible", and the body was normally left on the stake to be eaten by animals.

[47] Dale Allison, reviewing the arguments of Crossan and Ehrman, considers this assertion strong but "find[s] it likely that a man named Joseph, probably a Sanhedrist, from the obscure Arimathea, sought and obtained permission from the Roman authorities to make arrangements for Jesus’ hurried burial.

"[48] Raymond E. Brown, writing in 1973 before the publications of Hengel and Crossan, mentions that a number of authors have argued for a burial in a common grave, but Brown argues that the body of Jesus was buried in a new tomb by Joseph of Arimathea in accordance with Mosaic Law, which stated that a person hanged on a tree must not be allowed to remain there at night but should be buried before sundown.

[49] James Dunn dismisses the criticisms, stating that "the tradition is firm that Jesus was given a proper burial (Mark 15.42-47 pars.

[54] According to religion professor John Granger Cook, there are historical texts that mention mass graves, but they contain no indication of those bodies being dug up by animals.

Cook writes that "those texts show that the narrative of Joseph of Arimethaea's burial of Jesus would be perfectly comprehensible to a Greco-Roman reader of the gospels and historically credible."

Cook notes that numerous early critics of Christianity such Celsus, Porphyry, Hierocles, Julian, and Macarius’s anonymous pagan philosopher, accepted the historicity of the burial but rejected the resurrection.

"[60] while the Christmas carol "We Three Kings" includes the verse: Myrrh is mine, its bitter perfume Breathes a life of gathering gloom; Sorrowing, sighing, bleeding, dying, Sealed in the stone cold tomb.

"[61] In the Eastern Orthodox Church, the following troparion is sung on Holy Saturday: The noble Joseph, when he had taken down Thy most pure body from the tree, wrapped it in fine linen and anointed it with spices, and placed it in a new tomb.