Anointing

[1] By extension, the term is also applied to related acts of sprinkling, dousing, or smearing a person or object with any perfumed oil, milk, butter, or other fat.

Their use to introduce a divine influence or presence is recorded from the earliest times; anointing was thus used as a form of medicine, thought to rid persons and things of dangerous spirits and demons which were believed to cause disease.

This continues an earlier Hebrew practice most famously observed in the anointings of Aaron as high priest and both Saul and David by the prophet Samuel.

The concept is important to the figure of the Messiah or the Christ (Hebrew and Greek[3] for "The Anointed One") who appear prominently in Jewish and Christian theology and eschatology.

[1] It seems probable that its sanative purposes were enjoyed before it became an object of ceremonial religion, but the custom appears to predate written history and the archaeological record, and its genesis is impossible to determine with certainty.

[2] Anointing was also understood to "seal in" goodness and resist corruption, probably via analogy with the use of a top layer of oil to preserve wine in ancient amphoras, its spoiling usually being credited to demonic influence.

[n 3][11] In medieval and early modern Christianity, the practice was particularly associated with protection against vampires and ghouls who might otherwise take possession of the corpse.

[12] Anointing guests with oil as a mark of hospitality and token of honor is recorded in Egypt, Greece, and Rome, as well as in the Hebrew scriptures.

[11] In the sympathetic magic common to prehistoric and primitive religions, the fat of sacrificial animals and persons is often reckoned as a powerful charm, second to blood as the vehicle and seat of life.

[2][18] East African Arabs traditionally anointed themselves with lion's fat to gain courage and provoke fear in other animals.

[25] In Indian religion, late Vedic rituals developed involving the anointing of government officials, worshippers, and idols.

[citation needed] In modern Hinduism and Jainism, anointment is common, although the practice typically employs water or yoghurt, milk, or (particularly) butter[2] from the holy cow, rather than oil.

Many devotees are anointed as an act of consecration or blessing at every stage of life, with rituals accompanying birthing, educational enrollments, religious initiations, and death.

Buddhists may sprinkle assembled practitioners with water or mark idols of Buddha or the Bodhisattvas with cow or yak butter.

[33] Anointment by the chrism prepared according to the ceremony described in the Book of Exodus[34] was considered to impart the "Spirit of the Lord".

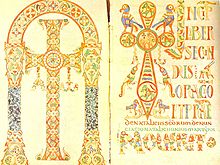

[citation needed] The practice of "chrismation" (baptism with oil) appears to have developed in the early church during the later 2nd century as a symbol of Christ, rebirth, and inspiration.

The ritual employs the sacred myron (μύρον, "chrism"), which is said to contain a remnant of oil blessed by the Twelve Apostles.

During chrismation, the "newly illuminate" person is anointed by using the myron to make the sign of the cross on the forehead, eyes, nostrils, lips, both ears, breast, hands, and feet.

Then, using his fingers, he takes some of the blessed oil floating on the surface of the baptismal water and anoints the catechumen on the forehead, breast, shoulders, ears, hands, and feet.

When an Orthodox Christian dies, if he has received the Mystery of Unction and some of the consecrated oil remains, it is poured over his body just before burial.

[12] Owing to their particular focus upon the action of the Holy Spirit, Pentecostal churches sometimes continue to employ anointing for consecration and ordination of pastors and elders, as well as for healing the sick.

[citation needed] The Pentecostal expression "the anointing breaks the yoke" derives from a passage in Isaiah[65] which discusses the power given the prophet Hezekiah by the Holy Spirit over the tyrant Sennacherib.

[67] The Doctrine and Covenants contains numerous references to anointing[68] and administration to the sick[69] by those with authority to perform the laying on of hands.

Alii modo non debent coronari, nec inungi sine istis: et si faciunt; ipsi abutuntur indebite.

[74]Later French legend held that a vial of oil, the Holy Ampulla, descended from Heaven to anoint Clovis I as the king of the Franks following his conversion to Christianity in 493.

[77][n 11] The ceremony, which closely followed the rite described by the Old Testament.,[79] was performed in 672 by Quiricus, the archbishop of Toledo;[77] It was apparently copied a year later when Flavius Paulus defected and joined the Septimanian rebels he had been tasked with quieting.

[n 12][80] The rite epitomized the Catholic Church's sanctioning the monarch's rule; it was notably employed by usurpers such as Pepin, whose dynasty replaced the Merovingians in 751.

The act is believed to empower him—through the grace of the Holy Spirit—with the ability to discharge his divinely appointed duties, particularly his ministry in defending the faith.

In Russian Orthodox ceremonial, the anointing took place during the coronation of the tsar towards the end of the service, just before his receipt of Holy Communion.

[citation needed] The utensils for the practice are sometimes reckoned as regalia, like the ampulla and spoon used in the Kingdom of France and the anointing horns used in Sweden and Norway.