Entropy as an arrow of time

Watching a single smoke particle buffeted by air, it would not be clear if a video was playing forwards or in reverse, and, in fact, it would not be possible as the laws which apply show T-symmetry.

As it drifts left or right, qualitatively it looks no different; it is only when the gas is studied at a macroscopic scale that the effects of entropy become noticeable (see Loschmidt's paradox).

By contrast, certain subatomic interactions involving the weak nuclear force violate the conservation of parity, but only very rarely.

The second law of thermodynamics is statistical in nature, and therefore its reliability arises from the huge number of particles present in macroscopic systems.

It is not impossible, in principle, for all 6 × 1023 atoms in a mole of a gas to spontaneously migrate to one half of a container; it is only fantastically unlikely—so unlikely that no macroscopic violation of the Second Law has ever been observed.

As the Universe grows, its temperature drops, which leaves less energy [per unit volume of space] available to perform work in the future than was available in the past.

If cosmic expansion were to halt and reverse due to gravity, the temperature of the Universe would once again grow hotter, but its entropy would also continue to increase due to the continued growth of perturbations and the eventual black hole formation,[3] until the latter stages of the Big Crunch when entropy would be lower than now.

[citation needed] Consider the situation in which a large container is filled with two separated liquids, for example a dye on one side and water on the other.

It would be reasonable to conclude that, without outside intervention, the liquid reached this state because it was more ordered in the past, when there was greater separation, and will be more disordered, or mixed, in the future.

However, for a large number of molecules it is so unlikely that one would have to wait, on average, many times longer than the current age of the universe for it to occur.

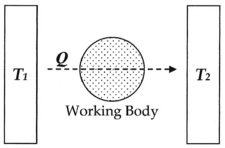

Entropy, defined as Q/T, was conceived by Rudolf Clausius as a function to measure the molecular irreversibility of this process, i.e. the dissipative work the atoms and molecules do on each other during the transformation.

This is an irreversible process, since if the box is full at the beginning (experiment B), it does not become only half-full later, except for the very unlikely situation where the gas particles have very special locations and speeds.

This is not correct for the final conditions of the system in experiment A, because the particles have interacted between themselves, so that their locations and speeds have become dependent on each other, i.e. correlated.

Now, by Liouville's theorem, time-reversal of all microscopic processes implies that the amount of information needed to describe the exact microstate of an isolated system (its information-theoretic joint entropy) is constant in time.

Phenomena that occur differently according to their time direction can ultimately be linked to the second law of thermodynamics[citation needed], for example ice cubes melt in hot coffee rather than assembling themselves out of the coffee and a block sliding on a rough surface slows down rather than speeds up.

The idea that we can remember the past and not the future is called the "psychological arrow of time" and it has deep connections with Maxwell's demon and the physics of information; memory is linked to the second law of thermodynamics if one views it as correlation between brain cells (or computer bits) and the outer world: Since such correlations increase with time, memory is linked to past events, rather than to future events[citation needed].

Current research focuses mainly on describing the thermodynamic arrow of time mathematically, either in classical or quantum systems, and on understanding its origin from the point of view of cosmological boundary conditions.

While the strong suspicion may be but a fleeting sense of intuition, it cannot be denied that, when there are multiple parameters, the field of partial differential equations comes into play.

[9] Mixing and ergodic systems do not have exact solutions, and thus proving time irreversibility in a mathematical sense is (as of 2006[update]) impossible.

In the case of the baker's map, it can be shown that several unique and inequivalent diagonalizations or bases exist, each with a different set of eigenvalues.

The transfer operator for more complex systems has not been consistently formulated, and its precise definition is mired in a variety of subtle difficulties.

In particular, it has not been shown that it has a broken symmetry for the simplest exactly-solvable continuous-time ergodic systems, such as Hadamard's billiards, or the Anosov flow on the tangent space of PSL(2,R).

One avenue is the study of rigged Hilbert spaces, and in particular, how discrete and continuous eigenvalue spectra intermingle[citation needed].

It is hoped that the study of Hilbert spaces with a similar inter-mingling will provide insight into the arrow of time.

Another distinct approach is through the study of quantum chaos by which attempts are made to quantize systems as classically chaotic, ergodic or mixing.

Because the eigenfunctions are fractals, much of the language and machinery of entropy and statistical mechanics can be imported to discuss and argue the quantum case.

[citation needed] Some processes that involve high energy particles and are governed by the weak force (such as K-meson decay) defy the symmetry between time directions.

In either case, the wave function collapse always follows quantum decoherence, a process which is understood to be a result of the second law of thermodynamics.

One could imagine at least two different scenarios, though in fact only the first one is plausible, as the other requires a highly smooth cosmic evolution, contrary to what is observed: In the first and more consensual scenario, it is the difference between the initial state and the final state of the universe that is responsible for the thermodynamic arrow of time.