Epidural blood patch

[7] EBPs are an invasive procedure but are safe and effective—further intervention is sometimes necessary, and repeat patches can be administered until symptoms resolve.

Factors such as pregnancy, having a low body mass index, being a female and young, increase the risk of dural puncture.

[13] As a result, many clinicians advise patients to lay flat and hydrate well to minimize the risk, but the efficacy of this practice has been questioned.

[3] Most PDPHs are self-limiting, so epidural blood patches are only used for people with moderate to severe cases who do not respond to conservative treatment.

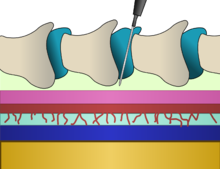

[16] For administration of an EBP due to PDPH, the level of prior epidural puncture is targeted;[15] blood injected for the most part spreads cranially.

[15] For EBPs, autologous blood is drawn from a peripheral vein;[2][17] the procedure uses a typical epidural needle.

[9] Blood from EBPs is spread throughout several segments within the epidural space, so it does not need to be injected at the same level as the puncture.

[19] When an EBP is administered a mass effect occurs which compresses the subarachnoid space, thereby increasing and modulating the pressure of the CSF, which translates intracranially.

[9] Some clinicians recommend obtaining blood cultures before administration of EBP to ensure the absence of infections.

[9] Though little large-scale clinical studies have been conducted, and no adverse effects have been reported thus far, EBP are a relative contraindication in patients with malignancies.

Rare side effects include subdural or spinal bleeding, infection, and seizure,[9] though EBPs do not carry a significant infectious risk even in immunocompromised people.

[10] As a result of the procedure, additional dural puncture can occur, which may increase the chance of inadvertently injecting blood intrathecally.

[17] EBPs are more likely to be successful with more than 22.5 mL of blood injected, and in people with less severe spinal CSF leakage.

[21] EBP may cause more side effects than a topical nerve block of the sphenopalatine neuron cell group in postpartum women though no large-scale clinical trials have been conducted.

Turan Ozdil, an anesthesiology instructor at the University of Tennessee, hypothesized how clotted blood could plug a hole in the dura while observing a car tire repair.

Anesthesiologist Anthony DiGiovanni refined Ozdil and Powell's technique, using 10 mL of blood to treat a person with unknown leakage locations.

DiGiovanni's staff member Burdett Dunbar wanted to more widely disseminate their technique, though their study was initially rejected by Anesthesiology until publication in Anesthesia & Analgesia in 1970.

Detractors such as Charles Bagley at Johns Hopkins University provided evidence against the treatment since 1928 as according to their studies blood in the CSF had significant side effects up to "severe convulsive seizures"; DiGiovanni disproved this in 1972.