Eric A. Havelock

Much of Havelock's work was devoted to addressing a single thesis: that all of Western thought is informed by a profound shift in the kinds of ideas available to the human mind at the point that Greek philosophy converted from an oral to a literate form.

Born in London on 3 June 1903, Havelock grew up in Scotland where he attended Greenock Academy[1] before enrolment at The Leys School in Cambridge, England, at the age of 14.

[1][3] While studying under F. M. Cornford at Cambridge, Havelock began to question the received wisdom about the nature of pre-Socratic philosophy and, in particular, about its relationship with Socratic thought.

In The Literate Revolution in Greece, his penultimate book, Havelock recalls being struck by a discrepancy between the language used by the philosophers he was studying and the heavily Platonic idiom with which it was interpreted in the standard texts.

[5] Havelock eventually came to the conclusion that the poetic aspects of early philosophy "were matters not of style but of substance",[6] and that such thinkers as Heraclitus and Empedocles actually have more in common even on an intellectual level with Homer than they do with Plato and Aristotle.

With his fellow academics Frank Underhill and Eugene Forsey, Havelock was a cofounder of the League for Social Reconstruction, an organisation of politically active socialist intellectuals.

All of the major newspapers in Toronto, along with a number of prominent business leaders, denounced the professors as radical leftists and their behaviour as unbecoming of academics.

After Havelock joined the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, along with several other members of the League, he was pressured by his superiors at the University to curtail his political activity.

The work Havelock and Innis began in the 1930s was the preliminary basis for the influential theories of communication developed by Marshall McLuhan and Edmund Snow Carpenter in the 1950s.

[17] He argued vociferously against the idea associated with John Burnet, which still had currency at the time, that the basic model for the theory of forms originated with Socrates.

Havelock's argument drew on evidence for a historical change in Greek philosophy; Plato, he argued, was fundamentally writing about the ideas of his present, not of the past.

He was active in a number of aspects of the University and of the department, of which he became chair; he undertook a translation of and commentary on Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound for the benefit of his students.

He was interested principally in Plato's much debated rejection of poetry in the Republic, in which his fictionalised Socrates argues that poetic mimesis—the representation of life in art—is bad for the soul.

Instead of concentrating on the philosophical definitions of key terms, as he had in his book on Democritus, Havelock turned to the Greek language itself, arguing that the meaning of words changed after the full development of written literature to admit a self-reflective subject; even pronouns, he said, had different functions.

Thus, the Platonic theory of forms in itself, Havelock claims, derives from a shift in the organisation of the Greek language, and ultimately comes down to a different function for and conception of the noun.

"[40] Homerists, like Platonists, found the book to be less than useful for the precise work of their own discipline; many classicists rejected outright Havelock's essential thesis that oral culture predominated through the 5th century.

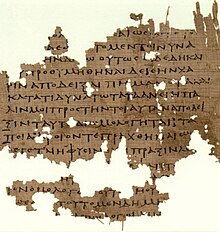

He wrote in 1977: The invention of the Greek alphabet, as opposed to all previous systems, including the Phoenician, constituted an event in the history of human culture, the importance of which has not as yet been fully grasped.

He said of the Dipylon inscription, a poetic line scratched into a vase and the earliest Greek writing known at the time, "Here in this casual act by an unknown hand there is announced a revolution which was destined to change the nature of human culture.

Walter J. Ong, for example, in assessing the significance of non-oral communication in an oral culture, cites Havelock's observation that scientific categories, which are necessary not only for the natural sciences but also for historical and philosophical analysis, depend on writing.

"[51] As a result of this refusal, Havelock seems to have been caught in a conflict of mere contradiction with his opponents, in which without attempt at refutation, he simply asserts repeatedly that philosophy is fundamentally literate in nature, and is countered only with a reminder that, as MacIntyre says, "Socrates wrote no books.

Delivered at Harvard on 16 March 1988, less than three weeks before his death, the lecture is framed principally in opposition to the University of Chicago philosopher Leo Strauss.