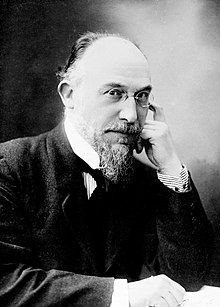

Erik Satie

A meeting with Jean Cocteau in 1915 led to the creation of the ballet Parade (1917) for Serge Diaghilev, with music by Satie, sets and costumes by Pablo Picasso, and choreography by Léonide Massine.

His harmony is often characterised by unresolved chords, he sometimes dispensed with bar-lines, as in his Gnossiennes, and his melodies are generally simple and often reflect his love of old church music.

Satie never married, and his home for most of his adult life was a single small room, first in Montmartre and, from 1898 to his death, in Arcueil, a suburb of Paris.

He adopted various images over the years, including a period in quasi-priestly dress, another in which he always wore identically coloured velvet suits, and is known for his last persona, in neat bourgeois costume, with bowler hat, wing collar, and umbrella.

Satie did not attend a school, but his father took him to lectures at the Collège de France and engaged a tutor to teach Eric Latin and Greek.

Before the boys returned to Paris from Honfleur, Alfred had met a piano teacher and salon composer, Eugénie Barnetche, whom he married in January 1879, to the dismay of the twelve-year-old Satie, who did not like her.

[7] Eugénie Satie resolved that her elder stepson should become a professional musician, and in November 1879 enrolled him in the preparatory piano class at the Paris Conservatoire.

[8] Satie strongly disliked the Conservatoire, which he described as "a vast, very uncomfortable, and rather ugly building; a sort of district prison with no beauty on the inside – nor on the outside, for that matter".

He spent much time in Notre-Dame de Paris contemplating the stained glass windows and in the National Library examining obscure medieval manuscripts.

[18] He quickly found army life no more to his liking than the Conservatoire, and deliberately contracted acute bronchitis by standing in the open, bare-chested, on a winter night.

By this time he had started what was to be an enduring friendship with the romantic poet Contamine de Latour, whose verse he set in some of his early compositions, which Satie senior published.

[8][26] Frequently short of money, Satie moved from his lodgings in the 9th arrondissement to a small room in the rue Cortot not far from Sacre-Coeur,[27] so high up the Butte Montmartre that he said he could see from his window all the way to the Belgian border.

[n 6] By mid-1892, Satie had composed the first pieces in a compositional system of his own making (Fête donnée par des Chevaliers Normands en l'honneur d'une jeune demoiselle), provided incidental music to a chivalric esoteric play (two Préludes du Nazaréen), had a hoax published (announcing the premiere of his non-existent Le bâtard de Tristan, an anti-Wagnerian opera),[29] and broken away from Péladan, starting that autumn with the "Uspud" project, a "Christian Ballet", in collaboration with Latour.

[30] He challenged the musical establishment by proposing himself – unsuccessfully – for the seat in the Académie des Beaux-Arts made vacant by the death of Ernest Guiraud.

[8] In 1898, in search of somewhere cheaper and quieter than Montmartre, Satie moved to a room in the southern suburbs, in the commune of Arcueil-Cachan, eight kilometres (five miles) from the centre of Paris.

[39] Only a few compositions that he took seriously remain from this period: Jack in the Box, music to a pantomime by Jules Depaquit (called a "clownerie" by Satie); Geneviève de Brabant, a short comic opera to a text by "Lord Cheminot" (Latour); Le poisson rêveur (The Dreamy Fish), piano music to accompany a lost tale by Cheminot, and a few others that were mostly incomplete.

[8] In a determined attempt to improve his technique, and against Debussy's advice, he enrolled as a mature student at Paris's second main music academy, the Schola Cantorum in October 1905, continuing his studies there until 1912.

[8] In October 1916 Satie received a commission from the Princesse de Polignac that resulted in what Orledge rates as the composer's masterpiece, Socrate, two years later.

He was in demand as a journalist, making contributions to the Revue musicale, Action, L'Esprit nouveau, the Paris-Journal[53] and other publications from the Dadaist 391[54] to the English-language magazines Vanity Fair and The Transatlantic Review.

[57] In 1924 the ballets Mercure (with choreography by Massine and décor by Picasso) and Relâche ("Cancelled") (in collaboration with Francis Picabia and René Clair), both provoked headlines with their first night scandals.

[13] Although his personal appearance was customarily immaculate, his room at Arcueil was in Orledge's word "squalid", and after his death the scores of several important works believed lost were found among the accumulated rubbish.

Having depended to a considerable extent on the generosity of friends in his early years, he was little better off when he began to earn a good income from his compositions, as he spent or gave away money as soon as he received it.

[60] In the view of the Oxford Dictionary of Music, Satie's importance lay in "directing a new generation of French composers away from Wagner‐influenced impressionism towards a leaner, more epigrammatic style".

They evoke the ancient world by what the critics Roger Nichols and Paul Griffiths describe as "pure simplicity, monotonous repetition, and highly original modal harmonies".

Orledge writes that this was partly because of his "trying to ape his illustrious peers … we find bits of Ravel in his miniature opera Geneviève de Brabant and echoes of both Fauré and Debussy in the Nouvelles pièces froides of 1907".

Orchestration, despite his studies with d'Indy, was never his strongest suit,[64] but his grasp of counterpoint is evident in the opening bars of Parade,[65] and from the outset of his composing career he had original and distinctive ideas about harmony.

[66] In his later years he composed sets of short instrumental works with absurd titles, including Veritables Preludes flasques (pour un chien) ("True Flabby Preludes (for a Dog)", 1912), Croquis et agaceries d'un gros bonhomme en bois ("Sketches and Exasperations of a Big Wooden Man", 1913) and Sonatine bureaucratique ("Bureaucratic Sonata", 1917).

In his neat, calligraphic hand,[67] Satie would write extensive instructions for his performers, and although his words appear at first sight to be humorous and deliberately nonsensical, Nichols and Griffiths comment, "a sensitive pianist can make much of injunctions such as 'arm yourself with clairvoyance' and 'with the end of your thought'".

[73] He wrote jeux d'esprit claiming to eat dinner in four minutes with a diet of exclusively white food (including bones and fruit mould), or to drink boiled wine mixed with fuchsia juice, or to be woken by a servant hourly throughout the night to have his temperature taken;[74] he wrote in praise of Beethoven's non-existent but "sumptuous" Tenth Symphony, and the family of instruments known as the cephalophones, "which have a compass of thirty octaves and are absolutely unplayable".

[76] He claimed the major influence on his humour was Oliver Cromwell, adding "I also owe much to Christopher Columbus, because the American spirit has occasionally tapped me on the shoulder and I have been delighted to feel its ironically glacial bite".