Etching revival

This came to an abrupt end after the 1929 Wall Street crash wrecked what had become a very strong market among collectors, at a time when the typical style of the movement, still based on 19th-century developments, was becoming outdated.

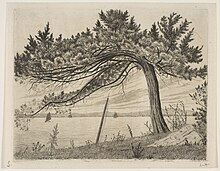

Charles-François Daubigny, Millet and especially Charles Jacque produced etchings that were different from those heavily worked reproductive plates of the previous century.

[7] The dark, grand and often vertical format townscapes of Charles Meryon, also mostly from the 1850s, provided models for a very different type of subject and style which was to remain in use until the end of the revival, though more in Britain than France.

This made the lines on the plates much more durable, and in particular the fragile "burr" thrown up by the drypoint process lasted much better than with copper alone, and so a greater (if still small) number of rich, burred, impressions could be produced.

Francis Seymour Haden and his brother-in-law, the American James McNeill Whistler were among the first to exploit this, and drypoint became a more popular technique than it had been since the 15th century, still often combined with conventional etching.

The publisher Alfred Cadart, the printer Auguste Delâtre, and Maxime Lalanne, an etcher who wrote a popular textbook of etching in 1866, established the broad contours of the movement.

Cadart founded the Société des Aquafortistes in 1862, reviving the awareness of the beautiful, original etching in the minds of the collecting public.

[12] Charles Meryon was an early inspiration, and close collaborator with Delâtre, laying out the various possible techniques of modern etching and producing works that would be ranked with Rembrandt and Dürer.

[16] It was Whistler who convinced the artist Alphonse Legros, one of the members of the French Revival, to come to London in 1863; later he was a professor at the Slade School of Fine Art.

The French, and later the Americans, were very interested in making lithographs, and in the long run this emerged as the dominant artistic printmaking technique, especially in the next century after the possibilities for using colour became greatly improved.

[27] The subjects have a notably large number of figures compared to earlier decades, and the artists include Whistler, Toulouse-Lautrec, Gauguin, Renoir, Pissarro, Paul Signac, Odilon Redon, Rodin, Henri Fantin-Latour, Félicien Rops and Puvis de Chavannes.

These were the "high priests" of the English movement: Muirhead Bone, David Young Cameron (these two both born and trained in Glasgow), and Frank Short.

In America, Stephen Parrish, Otto Bacher, Henry Farrer, and Robert Swain Gifford might be considered the important figures at the turn of the century, though they were mostly less exclusively dedicated to printmaking than the English artists.

The final generation of the revival are too numerous to name here but they might include such names as William Walcot, Frederick Griggs, Malcolm Osborne, James McBey, Ian Strang (son of William), and Edmund Blampied in Britain, John Sloan, Martin Lewis, Joseph Pennell and John Taylor Arms in the United States.

John Ruskin (despite having practised it to illustrate some of his books) described etching in 1872 as "an indolent and blundering art", objecting to both the reliance on chemical processes and mostly skilled printers to achieve the final image, and the perceived ease of the artist's role in creating it.

[32] To counter such criticisms, members of the movement wrote not only to explain the refinements of the technical processes, but to exalt original (rather than merely reproductive) etchings as creative works, with their own disciplines and artistic requirements.

Haden wrote: "I insist on a rapid execution, which pays little attention to detail", and thought that ideally the plate should be drawn in a single day's work, and bitten in front of the subject, or at least soon enough after seeing it to retain a good visual memory.

Haden had devised his own novel technique where the etching was drawn on the plate while it was immersed in a weak acid bath, so that the earliest lines were bitten the deepest; normally the drawing and biting were performed as different stages.

[34] In France Haden's ideas reflected a debate that had been underway for some decades over the comparative merits of quickly executed works such as the oil sketch, and the much lengthier process of making a finished painting.

[37] After rising to its highest in the 1920s, the market for collecting recent etchings collapsed in the Great Depression after the 1929 Wall Street crash, which after a period of "wild financial speculation" in prices, "made everything unsaleable".

However a record price of £250 was paid for Ayr Prison (1905) "Bone's masterpiece" (according to Dodgson) "as late as 1933", bought by Oskar Reinhart in Switzerland.

[39] Without a large group of collectors many artists returned to painting, though in the US from 1935 the Federal Art Project, part of the New Deal, put some money into printmaking.

As well as the Great Depression, the monochrome tradition of Haden and Whistler had reached something of a dead end, "largely resistant" to "the need to find recognisably modern subject-matter and forms of expression".

[40] A review in 1926 by Edward Hopper of Fine Prints of the Year, 1925 expressed this with some brutality: "We have had a long and weary familiarity with these 'true etchers' who spend their industrious lives weaving pleasing lines around old doorways, Venetian palaces, Gothic cathedrals, and English bridges on the copper ... One wanders through this desert of manual dexterity without much hope ... Of patient labour and skill there is in this book a plenty and more.