Euro area crisis

On 6 September 2012, the ECB calmed financial markets by announcing free unlimited support for all eurozone countries involved in a sovereign state bailout/precautionary programme from EFSF/ESM, through some yield lowering Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT).

[3][4] Comparative political economy explains the fundamental roots of the European crisis in varieties of national institutional structures of member countries (north vs. south), which conditioned their asymmetric development trends over time and made the union susceptible to external shocks.

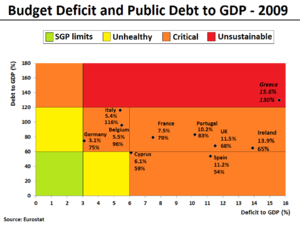

However, some of the signatories, including Germany and France, failed to stay within the confines of the Maastricht criteria and turned to securitising future government revenues to reduce their debts and/or deficits, sidestepping best practice and ignoring international standards.

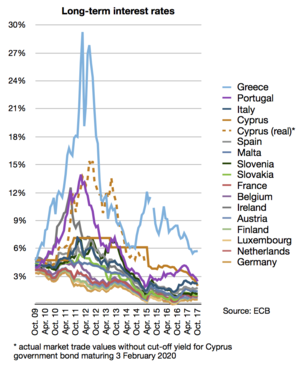

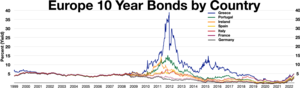

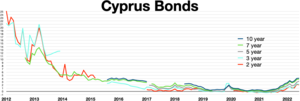

In mid-2012, due to successful fiscal consolidation and implementation of structural reforms in the countries being most at risk and various policy measures taken by EU leaders and the ECB (see below), financial stability in the eurozone improved significantly and interest rates fell steadily.

[41] Surprisingly, the Greek prime minister George Papandreou first answered that call by announcing a December 2011 referendum on the new bailout plan,[42][43] but had to back down amidst strong pressure from EU partners, who threatened to withhold an overdue €6 billion loan payment that Greece needed by mid-December.

[42][44] On 10 November 2011, Papandreou resigned following an agreement with the New Democracy party and the Popular Orthodox Rally to appoint non-MP technocrat Lucas Papademos as new prime minister of an interim national union government, with responsibility for implementing the needed austerity measures to pave the way for the second bailout loan.

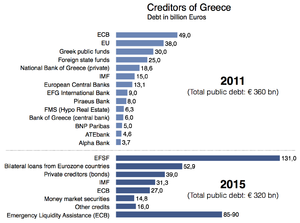

[83] According to a study by the European School of Management and Technology only €9.7bn or less than 5% of the first two bailout programs went to the Greek fiscal budget, while most of the money went to French and German banks[87] (In June 2010, France's and Germany's foreign claims vis-a-vis Greece were $57bn and $31bn respectively.

Due to a delayed reform schedule and a worsened economic recession, the new government immediately asked the Troika to be granted an extended deadline from 2015 to 2017 before being required to restore the budget into a self-financed situation; which in effect was equal to a request of a third bailout package for 2015–16 worth €32.6bn of extra loans.

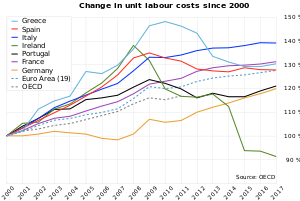

[103] The Financial Times special report on the future of the European Union argues that the liberalisation of labour markets has allowed Greece to narrow the cost-competitiveness gap with other southern eurozone countries by approximately 50% over the past two years.

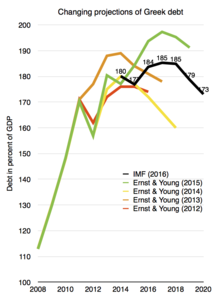

[110] The return of economic growth, along with the now existing underlying structural budget surplus of the general government, build the basis for the debt-to-GDP ratio to start a significant decline in the coming years ahead,[111] which will help ensure that Greece will be labelled "debt sustainable" and fully regain complete access to private lending markets in 2015.

The ECCL instrument is often used as a follow-up precautionary measure, when a state has exited its sovereign bailout programme, with transfers only taking place if adverse financial/economic circumstances materialize, but with the positive effect that it help calm down financial markets as the presence of this extra backup guarantee mechanism makes the environment safer for investors.

[115] This new fourth recession was widely assessed as being direct related to the premature snap parliamentary election called by the Greek parliament in December 2014 and the following formation of a Syriza-led government refusing to accept respecting the terms of its current bailout agreement.

Faced by the threat of a sovereign default and potential resulting exit of the eurozone, some final attempts were made by the Greek government in May 2015 to settle an agreement with the Troika about some adjusted terms for Greece to comply with in order to activate the transfer of the frozen bailout funds in its second programme.

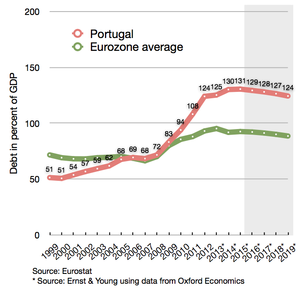

[113][151] According to the Financial Times special report on the future of the European Union, the Portuguese government has "made progress in reforming labour legislation, cutting previously generous redundancy payments by more than half and freeing smaller employers from collective bargaining obligations, all components of Portugal's €78 billion bailout program".

To build up trust in the financial markets, the government began to introduce austerity measures and in 2011 it passed a law in congress to approve an amendment to the Spanish Constitution to require a balanced budget at both the national and regional level by 2020.

[170][171][172] An economic forecast in June 2012 highlighted the need for the arranged bank recapitalisation support package, as the outlook promised a negative growth rate of 1.7%, unemployment rising to 25%, and a continued declining trend for housing prices.

[283] The EFSF is set to expire in 2013, running some months parallel to the permanent €500 billion rescue funding program called the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), which will start operating as soon as member states representing 90% of the capital commitments have ratified it.

... Government intervention should be the first resort, not the last resort.Beyond equity issuance and debt-to-equity conversion, then, one analyst "said that as banks find it more difficult to raise funds, they will move faster to cut down on loans and unload lagging assets" as they work to improve capital ratios.

[357][358] Apart from arguments over whether or not austerity, rather than increased or frozen spending, is a macroeconomic solution,[359] union leaders have also argued that the working population is being unjustly held responsible for the economic mismanagement errors of economists, investors, and bankers.

To minimise negative effects of such policies on purchasing power and economic activity the French government will partly offset the tax hikes by decreasing employees' social security contributions by €10 billion and by reducing the lower VAT for convenience goods (necessities) from 5.5% to 5%.

[393][394][395] In its spring 2012 economic forecast, the European Commission finds "some evidence that the current-account rebalancing is underpinned by changes in relative prices and competitiveness positions as well as gains in export market shares and expenditure switching in deficit countries".

[400] The key policy issue that has to be addressed in the long run is how to harmonise different political-economic institutional set-ups of the north and south European economies to promote economic growth and make the currency union sustainable.

Using the term "stability bonds", Jose Manuel Barroso insisted that any such plan would have to be matched by tight fiscal surveillance and economic policy coordination as an essential counterpart so as to avoid moral hazard and ensure sustainable public finances.

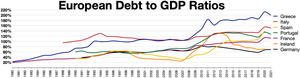

[421] A BIS study released in June 2012 warns that budgets of most advanced economies, excluding interest payments, "would need 20 consecutive years of surpluses exceeding 2 per cent of gross domestic product—starting now—just to bring the debt-to-GDP ratio back to its pre-crisis level".

First, the "no bail-out" clause (Article 125 TFEU) ensures that the responsibility for repaying public debt remains national and prevents risk premiums caused by unsound fiscal policies from spilling over to partner countries.

World Pensions Council (WPC) [fr] financial law and regulation experts have argued that the hastily drafted, unevenly transposed in national law, and poorly enforced EU rule on ratings agencies (Regulation EC N° 1060/2009) has had little effect on the way financial analysts and economists interpret data or on the potential for conflicts of interests created by the complex contractual arrangements between credit rating agencies and their clients"[466] Some in the Greek, Spanish, and French press and elsewhere spread conspiracy theories that claimed that the U.S. and Britain were deliberately promoting rumors about the euro in order to cause its collapse or to distract attention from their own economic vulnerabilities.

The Economist rebutted these "Anglo-Saxon conspiracy" claims, writing that although American and British traders overestimated the weakness of southern European public finances and the probability of the breakup of the eurozone, these sentiments were an ordinary market panic, rather than some deliberate plot.

[503] The Wall Street Journal conjectured as well that Germany could return to the Deutsche Mark,[504] or create another currency union[505] with the Netherlands, Austria, Finland, Luxembourg and other European countries such as Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the Baltics.

The Wall Street Journal added that without the German-led bloc, a residual euro would have the flexibility to keep interest rates low[508] and engage in quantitative easing or fiscal stimulus in support of a job-targeting economic policy[509] instead of inflation targeting in the current configuration.

[517] According to US author Ross Douthat "This would effectively turn the European Union into a kind of postmodern version of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire, with a Germanic elite presiding uneasily over a polyglot imperium and its restive local populations".