First Great Awakening

Opponents accused the revivals of fostering disorder and fanaticism within the churches by enabling uneducated, itinerant preachers and encouraging religious enthusiasm.

[3] Throughout the North American colonies, especially in the South, the revival movement increased the number of African slaves and free blacks who were exposed to (and subsequently converted to) Christianity.

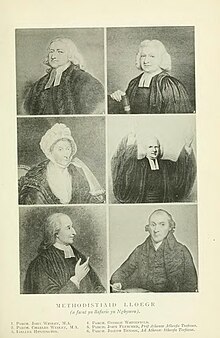

[1][10] In England, the major leaders of the Evangelical Revival were three Anglican priests: the brothers John and Charles Wesley and their friend George Whitefield.

They had been members of a religious society at Oxford University called the Holy Club and "Methodists" due to their methodical piety and rigorous asceticism.

Scougal wrote that many people mistakenly understood Christianity to be "Orthodox Notions and Opinions", "external Duties" or "rapturous Heats and extatic Devotion".

[17] In May 1738, Wesley attended a Moravian meeting on Aldersgate Street, where he felt spiritually transformed during a reading of Martin Luther's preface to the Epistle to the Romans.

[27] Three teachings that Methodists saw as the foundation of Christian faith were: The evangelicals responded vigorously to opposition—both literary criticism and even mob violence[30]—and thrived despite the attacks against them.

[36] At the same time, church membership was low because it had failed to keep up with population growth, and the influence of Enlightenment rationalism was leading many people to turn to atheism, Deism, Unitarianism, and Universalism.

"[38] In response to these trends, ministers influenced by New England Puritanism, Scots-Irish Presbyterianism, and European Pietism began calling for a revival of religion and piety.

[39] The blending of these three traditions would produce an evangelical Protestantism that placed greater importance "on seasons of revival, or outpourings of the Holy Spirit, and on converted sinners experiencing God's love personally.

Under Frelinghuysen's influence, Tennent came to believe that a definite conversion experience followed by assurance of salvation was the key mark of a Christian.

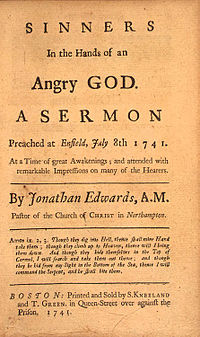

[47] At a time when Enlightenment rationalism and Arminian theology were popular among some Congregational clergy, Edwards held to traditional Calvinist doctrine.

[49] Edwards wrote an account of the Northampton revival, A Faithful Narrative, which was published in England through the efforts of prominent evangelicals John Guyse and Isaac Watts.

The last of Davenport's radical episodes took place in March 1743 in New London, when he ordered his followers to burn wigs, cloaks, rings, and other vanities.

[55] Following the intervention of two pro-revival "New Light" ministers, Davenport's mental state apparently improved, and he published a retraction of his earlier excesses.

The Old Lights saw the religious enthusiasm and itinerant preaching unleashed by the Awakening as disruptive to church order, preferring formal worship and a settled, university-educated ministry.

[61] Historian John Howard Smith noted that the Great Awakening made sectarianism an essential characteristic of American Christianity.

Evangelicals considered the new birth to be "a bond of fellowship that transcended disagreements on fine points of doctrine and polity", allowing Anglicans, Presbyterians, Congregationalists, and others to cooperate across denominational lines.

[65] In 1754, the efforts of Eleazar Wheelock led to what would become Dartmouth College, originally established to train Native American boys for missionary work among their own people.

Due to the fall of man, humans are naturally inclined to rebel against God and are unable to initiate or merit salvation, according to the doctrine of original sin.

The preaching of these doctrines resulted in the convicted feeling both guilty and totally helpless, since God was in complete control over whether they would be saved or not.

The revivalists use of "indiscriminate" evangelism—the "practice of extending the gospel promises to everyone in their audiences, without stressing that God redeems only those elected for salvation"—was contrary to these notions.

Samuel Blair described such responses to his preaching in 1740: "Several would be overcome and fainting; others deeply sobbing, hardly able to contain, others crying in a most dolorous manner, many others more silently weeping.

"[79] Moderate evangelicals took a cautious approach to this issue, neither encouraging nor discouraging these responses, but they recognized that people might express their conviction in different ways.

[80] Regeneration was always accompanied by saving faith, repentance, and love for God—all aspects of the conversion experience, which typically lasted several days or weeks under the guidance of a trained pastor.

Her beliefs were overt in her works; she describes the journey of being taken from a Pagan land to be exposed to Christianity in the colonies in a poem entitled "On Being Brought from Africa to America.

"[89][non-primary source needed] Wheatley became so influenced by the revivals and especially George Whitefield that she dedicated a poem to him after his death in which she referred to him as an "Impartial Saviour".

She was a Rhode Island schoolteacher, and her writings offer a glimpse into the spiritual and cultural upheaval of the time period, including a 1743 memoir, various diaries and letters, and her anonymously published The Nature, Certainty and Evidence of True Christianity (1753).

Caucasians began to welcome dark-skinned individuals into their churches, taking their religious experiences seriously while also admitting them to active roles in congregations as exhorters, deacons, and even preachers, although the last was a rarity.

[94][page needed] George Whitefield's sermons reiterated an egalitarian message but only translated into spiritual equality for Africans in the colonies, who mostly remained enslaved.