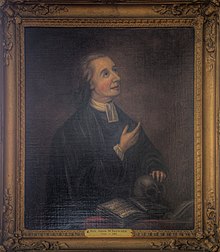

John William Fletcher

John William Fletcher (born Jean Guillaume de la Fléchère; 12 September 1729 – 14 August 1785) was a Swiss-born English divine and Methodist leader.

An accident prevented his sailing with his regiment to Brazil, and after a visit to Flanders, where an uncle offered to secure a commission for him, he went to England in 1750.

In the autumn of 1751,[5] he became tutor to the sons of Thomas and Susanna Hill, a wealthy Shropshire family, who spent part of the year in London.

On one of the family's stays in London, Fletcher first heard of the Methodists and became personally acquainted with John and Charles Wesley, as well as his future wife, Mary Bosanquet.

[3] He had developed a sincere religious and social concern for the people of this populous part of the West Midlands where he had first served in the Christian ministry, and here, for twenty-five years (1760–1785), he lived and worked with unique devotion and zeal, described by his wife as his, "unexampled labours" in the epitaph she penned for his iron tomb.

Indeed, much of Fletcher's controversial theological writings claimed their foundation was the 39 Articles, the Book of Common Prayer, and the Homilies of the Church of England.

[12] After his death, Mary Fletcher was allowed to continue living in the vicarage by the new vicar, Henry Burton, a pluralist clergyman who was also the incumbent of Atcham parish, near Shrewsbury.

Though John Wesley attempted to persuade Mrs. Fletcher to leave Madeley for a ministry with the Methodists in London, she refused, believing she was called to carry on her late husband's work in the parish.

Thomas Hatton, a like-minded clergyman from a neighbouring parish, Wesley wrote an elegiac sermon in the months after Fletcher's death, reflecting upon the text of Psalm 37:37, "Mark the perfect man".

The chief of his published works, written against Calvinism, were his Five Checks to Antinomianism, Scripture Scales, and his pastoral theology, Portrait of St Paul.

[3] Most of Fletcher's theological publications date from the period between 1770 and 1778, when there was great conflict between Wesley and the Methodists and British Calvinists (although, much of the thought found in these treatises can be traced to the early days of his ministry as the Vicar of Madeley).

His Portrait of St. Paul, written in French, but translated and published posthumously, fit well within the genre of clerical training books of the period.

"[17] Fletcher himself summarised his theological position: The error of rigid Calvinists centers in the denial of that evangelical liberty, whereby all men, under various dispensations of grace, may without necessity choose life [...] And the error of rigid Arminians consists in not paying a cheerful homage to redeeming grace, for all the liberty and power which we have to choose life, and to work righteousness since the fall [...] To avoid these two extremes, we need only follow the Scripture-doctrine of free-will restored and assisted by free-grace.