Exchange spring magnet

[3] The exchange spring magnet offers a geometry able to improve upon the previously reported maximum energy products of materials such as Rare Earth/Transition Metal complexes; while both materials have sufficiently large HC values and operate at relatively high Curie Temperatures, the exchange spring magnet can achieve much higher Msat values than the Rare Earth/Transition Metal (RE-TM) complexes.

The atomic moments' interactions with each other and with the externally applied field determine the behavior of the magnet.

Exchange coupling is a quantum mechanical effect that keeps the adjacent moments aligned with one another.

Along an axial direction, called the easy axis, the magnetic moments tend to align.

The opposite case applies to soft magnets, in which the magnetostatic energy is dominant.

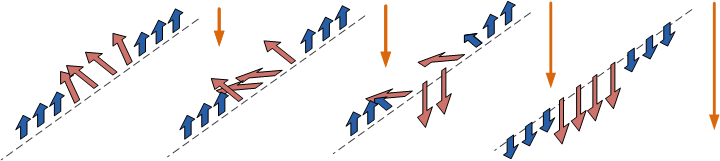

From left to right in Figure 3, an external field is first applied in an upward direction in order to saturate the magnet.

Since the coercivity of the hard phase is relatively high, the moments remain unchanged so as to minimize the anisotropy and exchange energy.

The magnetic moments in the soft phase start rotating to align with the applied field.

At the regions close to the interface, because of exchange coupling, the chain of magnetic moments acts like a spring.

The magnetic moments in the hard phase do not rotate until the external field is high enough that the exchange energy density in the transition region is comparable to the anisotropy energy density in the hard phase.

In the previous process, when the magnetic moments in the hard magnet start to rotate, the intensity of external field is already much higher than the coercivity of the soft phase, but there is still a transition region in soft phase.

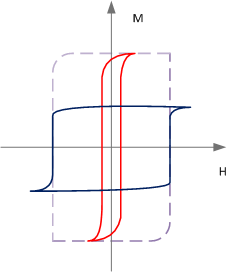

This phenomenon is shown in the hysteresis loop of an exchange spring magnet (Figure 6).

When the external field is removed, the remanent magnetization can recover to a value close to its original.

Additionally, the volume fraction of the soft phase needs to be as large as possible in order to achieve a high magnetization saturation.

One viable material geometry is to fabricate a magnet by embedding hard particles inside a soft matrix.

That way, the soft matrix material occupies the largest volume fraction while being close to the hard particles.

Since the total magnetization saturation is summed up by volume fraction, it is close to the value of a pure soft phase.

The fabrication of an exchange spring magnet requires precise control of the particle-matrix structure at the nanometer-scale dimension.