Exclusionary zoning

Exclusionary zoning was introduced in the early 1900s, typically to prevent racial and ethnic minorities from moving into middle- and upper-class neighborhoods.

Municipalities use zoning to limit population density, such as by prohibiting multi-family residential dwellings or setting minimum lot size requirements.

However, the noted urban planner Yale Rabin observed, "What began as a means of improving the blighted physical environment in which people lived and worked" became "a mechanism for protecting property values and excluding the undesirables."

The legislation established the institutional framework for zoning ordinances and delegated land-use power to local authorities for the conservation of community welfare and provided guidelines for appropriate regulation usage.

[8] In light of those developments, the Supreme Court considered zoning's constitutionality in the 1926 landmark case of Village of Euclid, Ohio v. Ambler Realty Co.

[9] After the end of World War II and the country's subsequent suburbanization process, exclusionary zoning policies experienced an uptick in complexity, stringency and prevalence as suburbanites attempted to more effectively protect their new communities.

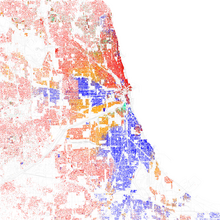

Thus, middle-class and affluent whites, who constituted the majority of suburban inhabitants, more frequently employed measures preventing immigrant and minority integration.

[9] Well-off whites mainly inhabited the suburbs, but the remaining city residents, primarily impoverished minorities, faced substantial obstacles to wealth.

The ability of minorities and other excluded populations to challenge exclusionary zoning became essentially nonexistent and has allowed the policy's unabated continuation.

Buchanan v. Warley 1917: A Louisville city ordinance prohibiting the sale of property in majority-white neighborhoods to black people was brought to court.

[11]: 96–97 Implicit within the case's ruling is permission for exclusionary zoning regulations to attempt preservation of identity in the context of family compositions.

Such concerns may manifest in measures prohibiting multi-family residential dwellings, limiting the number of people per unit of land and mandating lot size requirements.

[12] Another means by which exclusionary zoning and related ordinances contribute to the exclusion certain groups is through direct cost impositions on community residents.

In the 1970s, municipalities established measures decreeing developers greater responsibility in the provision and maintenance of many basic neighborhood resources such as schools, parks, and other related services.

According to one paywall study from 2004 by Robert Cervero and Michael Duncan, specific to Santa Clara County, California, increased property values and tax proceeds have resulted from racist and classist exclusionary practices.

[13] Surmised from one 1993 paywall study by William Bogart, in order to augment their own monetary assets, upper-class individuals enact regulations prohibiting neighborhood accessibility for specific groups.

Greater populations may lead to strains on potentially limited or vulnerable environmental resources such as water or air, if the urban form is designed in an automobile-dependent way.

[14] Some suburbanites also champion exclusionary zoning policies on the simple motivation of excluding unalike groups irrespective of any negative effects that they may impose.

Some researchers partly attribute the policies to class or racial prejudice as individuals often prefer to live in homogeneous communities of people similar to themselves.

[14] Thus, whites and upper classes divert those groups for their unsuitable characteristics, perceived link with negative neighborhood qualities and threat to community politics.

[17] Despite federal court mandates prohibiting blatant racial and economic discrimination, many of these less fortunate groups have encountered systematic obstacles preventing access to higher-income areas.

Residential segregation has remained constant from the 1960s to 1990s in spite of civil rights progress, primarily because of hindering policies that relegate certain groups to less-regulated areas.

Studies in Maryland and the District of Columbia find that higher densities cut per capita water and sewer installation costs by 50% and road installation/maintenance by 67%.

Regions with much economic segregation, which, as noted earlier, partially stems from exclusionary zoning, also have the largest gaps in test scores between the low-income and other students.