Residential segregation in the United States

Trends in residential segregation are attributed to discriminatory policies and practices, such as exclusionary zoning, location of public housing, redlining, disinvestment, and gentrification, as well as personal attitudes and preferences.

Residential segregation produces negative socioeconomic outcomes for minority groups, influencing disparities in wealth, educational opportunity, access to health care and food, and employment.

[6] World War II brought an influx of workers to cities looking for jobs, increasing the number of public housing projects.

[7] White families benefitted greatly from these programs, as it provided them with economic stability and accumulation of wealth due to increasing real estate values.

[9] An analysis of historical U.S. Census data by Harvard and Duke scholars indicates that racial separation has diminished significantly since the 1960s.

Published by the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, the report indicates that the dissimilarity index has declined in all 85 of the nation's largest cities.

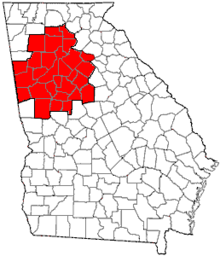

[12] Black people are hypersegregated in most of the largest metropolitan areas across the U.S., including Atlanta, Baltimore, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Houston, Los Angeles, New Orleans, New York, Philadelphia and Washington, DC.

[12] Analysis of patterns for income segregation come from the National Survey of America's Families, the Census and Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data.

Black and Hispanic low-income families, the two most racially segregated groups, rarely live in predominantly white or majority-white neighborhoods.

Incidents of exclusionary zoning separating households by race appeared as early as the 1870s and 1880s, when municipalities in California adopted anti-Chinese policies.

The prominent real estate developer J.C. Nichols was famous for creating master-planned communities with covenants that prohibited African Americans, Jews, and other races from owning his properties.

[20] Anti-discrimination laws passed after World War II led to a reduction in racial segregation for a short period of time, but as income-ineligible tenants were removed from public housing, the proportion of black residents increased.

[20] Three of the more infamous minority concentrated public housing projects in America were Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis and Cabrini-Green and Robert Taylor Homes in Chicago.

[20] This trend continued between 1964 and 1992, when a high density of projects were located in old core cities of metropolitan areas that were considered low income.

Residents in predominately minority neighborhoods were unable to obtain long-term mortgages on their homes because banks would not authorize loans for the redlined areas.

In some studies, real estate agents present fewer and more inferior options to black homeseekers than they do to whites with the same socioeconomic characteristics.

There is also criticism of the methods used to determine discrimination and it is not clear if paired testing accurately reflects the conditions in which people are actually searching for housing.

Other theories suggest demographic and socioeconomic factors such as age, gender and social class background influence residential choice.

[35] One empirical study completed in 2002 analyzed survey data from a random sample of blacks from Atlanta, Boston, Detroit and Los Angeles.

[35] The results of this study found that the housing preferences of blacks are largely attributed to discrimination and white hostility, not a desire to live with a similar racial group.

Critics of these theories suggest that the survey questions used in the research design for these studies imply that race is a greater factor in residential choice than access to schools, transportation, and jobs.

For example, a 2009 study by researcher Walton found that residential segregation paired with poverty led to lower birth weights in Black communities.

Urban heat islands are areas of cities that have much higher temperatures than other neighborhoods due to a high amount of concrete and a lack of trees and green spaces.

[21] The passage of fair housing laws provided an opportunity for legal recourse against local and federal agencies that segregated residents and prohibited integrated communities.

The 1976 court decision resulted in HUD and CHA agreeing to mediate segregation imposed on Chicago public housing residents by providing Section 8 voucher assistance to more than 7,000 black families.

Policymakers theorized that housing mobility would provide residents with access to "social capital", including ties to informal job networks.

[53] In addition to the MTO program, the federal government provided funding to demolish 100,000 of the nation's worst public housing units and rebuild the projects with mixed income communities.

[55] According to the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the current state of residential segregation, largely by race, occurred due to housing development practices and city infrastructure changes during the 20th century.

[59] In order to implement new housing programs and interstates throughout the 20th century, the City of Atlanta chose to remove many poor or low income neighborhoods.

[63] In the 1940s, 80% of property outside of the inner-city limits was controlled by racially restrictive covenants, barring Black families from buying homes in these neighborhoods.