Exploration of Pluto

The exploration of Pluto began with the arrival of the New Horizons probe in July 2015, though proposals for such a mission had been studied for many decades.

In May 1989, a group of scientists and engineers, including Alan Stern and Fran Bagenal, formed an alliance called the "Pluto Underground".

The group started a letter writing campaign which aimed to bring to attention Pluto as a viable target for exploration.

[11] The spacecraft's minimalistic design was to allow it to travel faster and be more cost-effective, in contrast to most other big-budget projects NASA were developing at the time, such as Galileo and Cassini.

Doubts about the cost-effectiveness were raised by Farquhar's team as Pluto had just passed perihelion, which would exponentially increase the mission duration before the launch date was finalized.

Pluto's approximate axial tilt of 118 degrees meant that the southern hemisphere would not be able to be photographed as it entered decades-long darkness with the onset of winter.

In October 1991, the United States Postal Service released a series of stamps commemorating NASA's exploration of the Solar System.

[18] That year, Staehle, with the help of JPL engineers and students from the California Institute of Technology, formed the Pluto Fast Flyby project.

Additionally, morale among the team and personnel working on interplanetary missions was low following the loss of the Mars Observer spacecraft in August 1993.

Alan Stern would later cite that event as a significant factor towards the low enthusiasm for the Pluto Fast Flyby project.

[21] After an intense political battle, a revised mission to Pluto called New Horizons was granted funding from the US government in 2003.

The mission leader, S. Alan Stern, confirmed that some of the ashes of Clyde Tombaugh, who died in 1997, had been placed aboard the spacecraft.

[24] The images, taken from a distance of approximately 4.2 billion kilometers, confirmed the spacecraft's ability to track distant targets, critical for maneuvering toward Pluto and other Kuiper belt objects.

On 20 March 2015, NASA invited the general public to suggest names for surface features that will be discovered on Pluto and Charon.

[27] Between April and June 2015, New Horizons began returning images of Pluto that exceeded the quality that the Hubble Space Telescope could produce.

[28][29] Pluto's small moons, discovered shortly before and after the probe's launch, were considered to be potentially hazardous, as debris from collisions between them and other Kuiper belt objects could have produced a tenuous dusty ring.

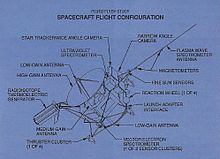

New Horizons used a remote sensing package that includes imaging instruments and a radio science investigation tool, as well as spectroscopic and other experiments, to characterize the global geology and morphology of Pluto and its moon Charon, map their surface composition and analyze Pluto's neutral atmosphere and its escape rate.

According to New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, “If we send an orbiter, we can map 100 percent of the planet, even terrains that are in total shadow.

"[33] Stern and David Grinspoon have also suggested that an orbiter mission could search for evidence of the subsurface ocean hinted at in New Horizons data.

The Fusion-Enabled Pluto Orbiter and Lander was a 2017 phase I report funded by the NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program.

[3][36] The report, written by principal investigator Stephanie Thomas of Princeton Satellite Systems, Inc., describes a Direct Fusion Drive (DFD) mission to Pluto.