Expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia

[18] Following the Munich Agreement of 1938, and the subsequent Occupation of Bohemia and Moravia by Hitler in March 1939, Edvard Beneš set out to convince the Allies during World War II that the expulsion of ethnic Germans was the best solution.

Although the details changed, along with British public and official opinion, and pressure from Czech resistance groups, the broad goals of the Czechoslovak Government-in-Exile remained the same throughout the war.

[23] Initially, only a few hundred thousand Sudeten Germans were to be affected — people who were perceived as being disloyal to Czechoslovakia and who, according to Beneš and Czech public opinion, had acted as Hitler's "fifth column".

The idea of expelling ethnic Germans from Czechoslovakia was supported by the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill[24] and Britain's Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden.

[2] The April 1945 Košice Program, which outlined the postwar political settlement of Czechoslovakia, stipulated an expulsion of Germans and Hungarians from the country.

Geoffrey Harrison, who drafted article XIII of the Potsdam Communique concerning the expulsions, wrote on 31 July 1945 to John Troutbeck, head of the German Department at the Foreign Office: "The Sub-Committee met three times, taking as a basis of discussion a draft which I circulated ... Sobolov took the view that the Polish and Czechoslovak wish to expel their German populations was the fulfilment of an historic mission which the Soviet Government were unwilling to try to impede. ...

Among these spontaneous events was the removal and detention of the Sudeten Germans which was triggered by the strong anti-German sentiment at the grass-roots level and organized by local officials.

According to the Schieder commission, records of food rationing coupons show approximately 3,070,899 inhabitants of occupied Sudetenland in January 1945, which included Czechs or other non-Germans.

[27] From London and Moscow, Czech and Slovak political agents in exile followed an advancing Soviet army pursuing German forces westward, to reach the territory of the first former Czechoslovak Republic.

After the proclamation of the Košice program, the German and Hungarian population living in the reborn Czechoslovak state were subjected to various forms of court procedures, citizenship revocations, property confiscation, condemnation to forced labour camps, and appointment of government managers to German and Hungarian owned businesses and farms, referred to euphemistically as "reslovakization".

General Zdeněk Novák, head of the Prague military command "Alex", issued an order to "deport all Germans from territory within the historical borders.

"[28] On 15 June, a government decree directed the army to implement measures to apprehend Nazi criminals and carry out the transfer of the German population.

"The Conference reached the following agreement on the removal of Germans from Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary:— The three Governments (The United States, Great Britain and Soviet Union), having considered the question in all its aspects, recognize that the transfer to Germany of German populations or elements thereof, remaining in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, will have to be undertaken.

[34][35]The 1945 expulsion was referred to as the "wild transfer" (divoký odsun) due to the widespread violence and brutality that were not only perpetuated by mobs but also by soldiers, police, and others acting under the colour of authority.

The following examples are described in a study done by the European University Institute in Florence:[37] During the wild transfer phase, it is estimated that the number of murdered Germans was between 19,000 and 30,000.

[44] A 1964 report by the German Red Cross stated that 1,215 "internment camps" were established, as well as 846 forced labour and "disciplinary centres", and 215 prisons, on Czechoslovak territory.

Allied authorities in the American and British zones were able to investigate several cases, including the notorious concentration camp at České Budějovice in Southern Bohemia.

[13][14][15][17] Czech records report 15,000–16,000 deaths not including an additional 6,667 unexplained cases or suicides during the expulsion,[50] and others died from hunger and illness in Germany as a consequence.

Activities (which would otherwise be considered criminal), were not illegal if their "objective was to contribute to the fight for regaining of freedom of Czechs and Slovaks or were aimed at righteous retaliation for deeds of occupants or their collaborators".

The Czech side regrets that, by the forcible expulsion and forced resettlement of Sudeten Germans from the former Czechoslovakia after the war as well as by the expropriation and deprivation of citizenship, much suffering and injustice was inflicted upon innocent people, also in view of the fact that guilt was attributed collectively.

"Czech–German Declaration 1997The joint Czech–German commission of historians in 1996 stated the following numbers: the deaths caused by violence and abnormal living conditions amount approximately to 10,000 persons killed; another 5,000–6,000 persons died of unspecified reasons related to expulsion; making the total number of victims of the expulsion 15,000–16,000 (this excludes suicides, which make another approximately 3,400 cases).

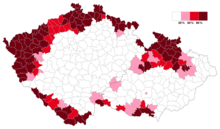

[13][14][15][17] The Communist Party controlled the distribution of seized German assets, contributing to its popularity in the border areas, where it won 75 per cent of votes in the 1946 election.

[56] According to an article in the Prague Daily Monitor: The Czech–German Declaration [of] 1997 has achieved a compromise and expressed regret over the wrongs caused to innocent people by "the post-war expulsions as well as forced deportations of Sudeten Germans from Czechoslovakia, expropriation and stripping of citizenship" on the basis of the principle of collective guilt.In the Czech–German Declaration of August, 1997: The German side took full responsibility for the crimes of the Nazi regime and their consequences (the allied expulsion).

"The German side is conscious of the fact that the National Socialist policy of violence towards the Czech people helped to prepare the ground for post-war flight, forcible expulsion and forced resettlement.

""The Czech side regrets that, by the forcible expulsion and forced resettlement of Sudeten Germans from the former Czechoslovakia after the war ..., much suffering and injustice was inflicted upon innocent people.

Since the Czechoslovak government-in-exile decided that population transfer was the only solution of the German question, the problem of reparation (war indemnity) was closely associated.

The proposed population transfer as presented in negotiations with the governments of U.S., UK and U.S.S.R., presumed the confiscation of the Germans' property to cover the reparation demands of Czechoslovakia; then Germany should pay the compensation to satisfy its citizens.

The IARA ended its activity in 1959 and the status quo is as follows: the Czech Republic kept the property of expelled ethnic Germans while Germany did not pay any reparations (only about 0.5% of Czechoslovak demands were satisfied [62]).

For this reason, every time the Sudeten Germans request compensation or the abolition of the Beneš decrees, the Czech side strikes back by the threat of reparation demands.

[63] Other sources state an overall amount of roughly 60bn EUR paid out as partial compensation to all citizens of Germany and ethnic-German expellees — a group of 15m people alone — affected by property loss due to consequences of the war.