Extinction event

[5] In May 2020, studies suggested that the causes of the mass extinction were global warming, related to volcanism, and anoxia, and not, as considered earlier, cooling and glaciation.

[9] Most recently, the deposition of volcanic ash has been suggested to be the trigger for reductions in atmospheric carbon dioxide leading to the glaciation and anoxia observed in the geological record.

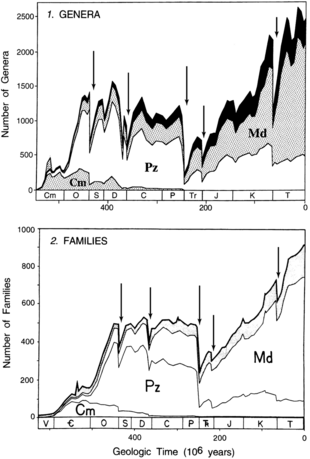

[11] Sepkoski and Raup (1982)[2] did not initially consider the Late Devonian extinction interval (Givetian, Frasnian, and Famennian stages) to be statistically significant.

This is because: It has been suggested that the apparent variations in marine biodiversity may actually be an artifact, with abundance estimates directly related to quantity of rock available for sampling from different time periods.

A quantification of the rock exposure of Western Europe indicates that many of the minor events for which a biological explanation has been sought are most readily explained by sampling bias.

[41][42] Later papers by Sepkoski and other authors switched to genera, which are more precise than families and less prone to taxonomic bias or incomplete sampling relative to species.

Mass extinctions, though acknowledged, were considered mysterious exceptions to the prevailing gradualistic view of prehistory, where slow evolutionary trends define faunal changes.

The first breakthrough was published in 1980 by a team led by Luis Alvarez, who discovered trace metal evidence for an asteroid impact at the end of the Cretaceous period.

Around the same time, Sepkoski began to devise a compendium of marine animal genera, which would allow researchers to explore extinction at a finer taxonomic resolution.

Many paleontologists opt to assess diversity trends by randomized sampling and rarefaction of fossil abundances rather than raw temporal range data, in order to account for all of these biases.

[60][65][3] Alroy (2010) attempted to circumvent sample size-related biases in diversity estimates using a method he called "shareholder quorum subsampling" (SQS).

The end-Cretaceous mass extinction removed the non-avian dinosaurs and made it possible for mammals to expand into the large terrestrial vertebrate niches.

Another point of view put forward in the Escalation hypothesis predicts that species in ecological niches with more organism-to-organism conflict will be less likely to survive extinctions.

This is because the very traits that keep a species numerous and viable under fairly static conditions become a burden once population levels fall among competing organisms during the dynamics of an extinction event.

[79] However, clades that survive for a considerable period of time after a mass extinction, and which were reduced to only a few species, are likely to have experienced a rebound effect called the "push of the past".

[80] Darwin was firmly of the opinion that biotic interactions, such as competition for food and space – the 'struggle for existence' – were of considerably greater importance in promoting evolution and extinction than changes in the physical environment.

[83] Various ideas, mostly regarding astronomical influences, attempt to explain the supposed pattern, including the presence of a hypothetical companion star to the Sun,[84][85] oscillations in the galactic plane, or passage through the Milky Way's spiral arms.

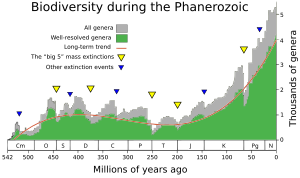

[93] Over the course of the Phanerozoic, individual taxa appear to have become less likely to suffer extinction,[94] which may reflect more robust food webs, as well as fewer extinction-prone species, and other factors such as continental distribution.

[139] These are often clearly marked by worldwide sequences of contemporaneous sediments that show all or part of a transition from sea-bed to tidal zone to beach to dry land – and where there is no evidence that the rocks in the relevant areas were raised by geological processes such as orogeny.

[143] The impact of a sufficiently large asteroid or comet could have caused food chains to collapse both on land and at sea by producing dust and particulate aerosols and thus inhibiting photosynthesis.

[144] Impacts on sulfur-rich rocks could have emitted sulfur oxides precipitating as poisonous acid rain, contributing further to the collapse of food chains.

[155] Alternatively, the Sun's passage through the higher density spiral arms of the galaxy could coincide with mass extinction on Earth, perhaps due to increased impact events.

[157] A nearby gamma-ray burst (less than 6000 light-years away) would be powerful enough to destroy the Earth's ozone layer, leaving organisms vulnerable to ultraviolet radiation from the Sun.

The glaciation cycles of the current ice age are believed to have had only a very mild impact on biodiversity, so the mere existence of a significant cooling is not sufficient on its own to explain a mass extinction.

[183] British oceanologist and atmospheric scientist, Andrew Watson, explained that, while the Holocene epoch exhibits many processes reminiscent of those that have contributed to past anoxic events, full-scale ocean anoxia would take "thousands of years to develop".

[188] Movement of the continents into some configurations can cause or contribute to extinctions in several ways: by initiating or ending ice ages; by changing ocean and wind currents and thus altering climate; by opening seaways or land bridges that expose previously isolated species to competition for which they are poorly adapted (for example, the extinction of most of South America's native ungulates and all of its large metatherians after the creation of a land bridge between North and South America).

Pangaea was almost fully formed at the transition from mid-Permian to late-Permian, and the "Marine genus diversity" diagram at the top of this article shows a level of extinction starting at that time, which might have qualified for inclusion in the "Big Five" if it were not overshadowed by the "Great Dying" at the end of the Permian.

A study published in May 2017 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences argued that a "biological annihilation" akin to a sixth mass extinction event is underway as a result of anthropogenic causes, such as over-population and over-consumption.

The eventual warming and expanding of the Sun, combined with the eventual decline of atmospheric carbon dioxide, could actually cause an even greater mass extinction, having the potential to wipe out even microbes (in other words, the Earth would be completely sterilized): rising global temperatures caused by the expanding Sun would gradually increase the rate of weathering, which would in turn remove more and more CO2 from the atmosphere.

[197] Subsequent to the P-T extinction, there was an increase in provincialization, with species occupying smaller ranges – perhaps removing incumbents from niches and setting the stage for an eventual rediversification.