Extrapolation

A sound choice of which extrapolation method to apply relies on a priori knowledge of the process that created the existing data points.

Some experts have proposed the use of causal forces in the evaluation of extrapolation methods.

[2] Crucial questions are, for example, if the data can be assumed to be continuous, smooth, possibly periodic, etc.

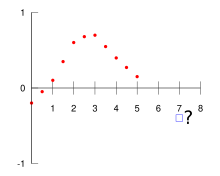

Linear extrapolation means creating a tangent line at the end of the known data and extending it beyond that limit.

If the conic section created is an ellipse or circle, when extrapolated it will loop back and rejoin itself.

An extrapolated parabola or hyperbola will not rejoin itself, but may curve back relative to the X-axis.

French curve extrapolation is a method suitable for any distribution that has a tendency to be exponential, but with accelerating or decelerating factors.

[4] Can be created with 3 points of a sequence and the "moment" or "index", this type of extrapolation have 100% accuracy in predictions in a big percentage of known series database (OEIS).

If the method assumes the data are smooth, then a non-smooth function will be poorly extrapolated.

In terms of complex time series, some experts have discovered that extrapolation is more accurate when performed through the decomposition of causal forces.

The classic example is truncated power series representations of sin(x) and related trigonometric functions.

Away from x = 0 however, the extrapolation moves arbitrarily away from the x-axis while sin(x) remains in the interval [−1, 1].

In particular, the compactification point at infinity is mapped to the origin and vice versa.

Care must be taken with this transform however, since the original function may have had "features", for example poles and other singularities, at infinity that were not evident from the sampled data.

Another problem of extrapolation is loosely related to the problem of analytic continuation, where (typically) a power series representation of a function is expanded at one of its points of convergence to produce a power series with a larger radius of convergence.

Again, analytic continuation can be thwarted by function features that were not evident from the initial data.

Also, one may use sequence transformations like Padé approximants and Levin-type sequence transformations as extrapolation methods that lead to a summation of power series that are divergent outside the original radius of convergence.

If this data needs to be convoluted to a known kernel function, the numerical calculations will increase N log(N) times even with fast Fourier transform (FFT).

There exists an algorithm, it analytically calculates the contribution from the part of the extrapolated data.

For example, we believe in the reality of what we see through magnifying glasses because it agrees with what we see with the naked eye but extends beyond it; we believe in what we see through light microscopes because it agrees with what we see through magnifying glasses but extends beyond it; and similarly for electron microscopes.