Eye

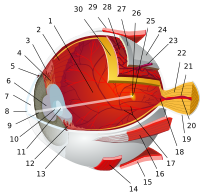

In higher organisms, the eye is a complex optical system that collects light from the surrounding environment, regulates its intensity through a diaphragm, focuses it through an adjustable assembly of lenses to form an image, converts this image into a set of electrical signals, and transmits these signals to the brain through neural pathways that connect the eye via the optic nerve to the visual cortex and other areas of the brain.

In an organism that has more complex eyes, retinal photosensitive ganglion cells send signals along the retinohypothalamic tract to the suprachiasmatic nuclei to effect circadian adjustment and to the pretectal area to control the pupillary light reflex.

In other organisms, particularly prey animals, eyes are located to maximise the field of view, such as in rabbits and horses, which have monocular vision.

Such eyes are typically spheroid, filled with the transparent gel-like vitreous humour, possess a focusing lens, and often an iris.

[12] Every technological method of capturing an optical image that humans commonly use occurs in nature, with the exception of zoom and Fresnel lenses.

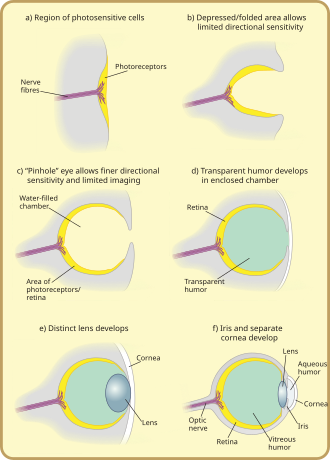

The directionality can be improved by reducing the size of the aperture, by incorporating a reflective layer behind the receptor cells, or by filling the pit with a refractile material.

[16] No extant aquatic organisms possess homogeneous lenses; presumably the evolutionary pressure for a heterogeneous lens is great enough for this stage to be quickly "outgrown".

Ocelli (pit-type eyes of arthropods) blur the image across the whole retina, and are consequently excellent at responding to rapid changes in light intensity across the whole visual field; this fast response is further accelerated by the large nerve bundles which rush the information to the brain.

Multiple lenses are seen in some hunters such as eagles and jumping spiders, which have a refractive cornea: these have a negative lens, enlarging the observed image by up to 50% over the receptor cells, thus increasing their optical resolution.

[1] In the eyes of most mammals, birds, reptiles, and most other terrestrial vertebrates (along with spiders and some insect larvae) the vitreous fluid has a higher refractive index than the air.

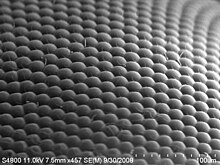

The image perceived is a combination of inputs from the numerous ommatidia (individual "eye units"), which are located on a convex surface, thus pointing in slightly different directions.

[19] Because the individual lenses are so small, the effects of diffraction impose a limit on the possible resolution that can be obtained (assuming that they do not function as phased arrays).

They are also possessed by Limulus, the horseshoe crab, and there are suggestions that other chelicerates developed their simple eyes by reduction from a compound starting point.

Long-bodied decapod crustaceans such as shrimp, prawns, crayfish and lobsters are alone in having reflecting superposition eyes, which also have a transparent gap but use corner mirrors instead of lenses.

[8] Another kind of compound eye, found in males of Order Strepsiptera, employs a series of simple eyes—eyes having one opening that provides light for an entire image-forming retina.

[1] Good fliers such as flies or honey bees, or prey-catching insects such as praying mantis or dragonflies, have specialised zones of ommatidia organised into a fovea area which gives acute vision.

The tube feet of sea urchins contain photoreceptor proteins, which together act as a compound eye; they lack screening pigments, but can detect the directionality of light by the shadow cast by its opaque body.

It is of rather similar composition to the cornea, but contains very few cells (mostly phagocytes which remove unwanted cellular debris in the visual field, as well as the hyalocytes of Balazs of the surface of the vitreous, which reprocess the hyaluronic acid), no blood vessels, and 98–99% of its volume is water (as opposed to 75% in the cornea) with salts, sugars, vitrosin (a type of collagen), a network of collagen type II fibres with the mucopolysaccharide hyaluronic acid, and also a wide array of proteins in micro amounts.

The majority of the advancements in early eyes are believed to have taken only a few million years to develop, since the first predator to gain true imaging would have touched off an "arms race"[35] among all species that did not flee the photopic environment.

Hence multiple eye types and subtypes developed in parallel (except those of groups, such as the vertebrates, that were only forced into the photopic environment at a late stage).

The pit deepened over time, the opening diminished in size, and the number of photoreceptor cells increased, forming an effective pinhole camera that was capable of dimly distinguishing shapes.

[38] However, the ancestors of modern hagfish, thought to be the protovertebrate,[36] were evidently pushed to very deep, dark waters, where they were less vulnerable to sighted predators, and where it is advantageous to have a convex eye-spot, which gathers more light than a flat or concave one.

[39] The gap between tissue layers naturally formed a biconvex shape, an optimally ideal structure for a normal refractive index.

For instance, the distribution of photoreceptors tends to match the area in which the highest acuity is required, with horizon-scanning organisms, such as those that live on the African plains, having a horizontal line of high-density ganglia, while tree-dwelling creatures which require good all-round vision tend to have a symmetrical distribution of ganglia, with acuity decreasing outwards from the centre.

Their eyes are almost divided into two, with the upper region thought to be involved in detecting the silhouettes of potential prey—or predators—against the faint light of the sky above.

Accordingly, deeper water hyperiids, where the light against which the silhouettes must be compared is dimmer, have larger "upper-eyes", and may lose the lower portion of their eyes altogether.

[40] Eyes may be mounted on stalks to provide better all-round vision, by lifting them above an organism's carapace; this also allows them to track predators or prey without moving the head.

At a pupil diameter of 3 mm, the spherical aberration is greatly reduced, resulting in an improved resolution of approximately 1.7 arcminutes per line pair.

With a few exceptions (snakes, placental mammals), most organisms avoid these effects by having absorbent oil droplets around their cone cells.

When rods and cones are stimulated by light, they connect through adjoining cells within the retina to send an electrical signal to the optic nerve fibres.