Spirou & Fantasio

[2][3] Adding to the difficulties of magazine publication that came with the outbreak of World War II, Velter joined the army effort, and his wife Blanche Dumoulin, using the pen name Davine, continued the work on the Spirou strip, with the aid of the young Belgian artist Luc Lafnet.

He introduced a large gallery of recurring characters, notably the Count de Champignac, an elderly scientist and inventor; the buffoonish mad scientist Zorglub; Fantasio's cousin and aspiring dictator Zantafio; and the journalist Seccotine, a rare instance of a major female character in Franco-Belgian comics of this period.

One Franquin creation that went on to develop a life of its own was the Marsupilami, a fictional monkey-like creature with a tremendously long prehensile tail.

However, as Franquin grew tired of Spirou, his other major character Gaston began to take precedence in his work, and following the controversial Panade à Champignac, the series passed on to a then-unknown young cartoonist, Jean-Claude Fournier, in 1969.

Starting with Du glucose pour Noémie, there would be no more appearances of the Marsupilami in Spirou et Fantasio, with the exception of a few discreet references.

Where Franquin's stories tended to be politically neutral (in his later works, notably Idées noires, he would champion pacifist and environmental views), Fournier's stint on Spirou addressed such hot topics (for the 1970s) as nuclear energy (L'Ankou), drug-funded dictatorships (Kodo le tyran) and Duvalier-style repression (Tora Torapa).

Fournier introduced some new characters such as Ororéa, a beautiful girl reporter with whom Fantasio was madly in love (in contrast with his dislike of Seccotine); Itoh Kata, a Japanese magician; and an occult SPECTRE-like criminal organisation known as The Triangle.

None of these were reused by later artists until some thirty years later when Itoh Kata appeared in Morvan and Munuera's Spirou et Fantasio à Tokyo.

Their primary addition to the Spirou universe, namely the "Black box", a device that annihilates sound, is in fact an acknowledged rehash from an early Sophie story by Jidéhem (La bulle du silence).

This unfinished story was first collected in an unofficial album in 1984, À la recherche de Bocongo, and then, legally, under the name of Cœurs d'acier (Champaka editor, 1990).

This last edition includes the original strips, and a text by Yann Le Pennetier, illustrated by Chaland, that finishes the interrupted story.

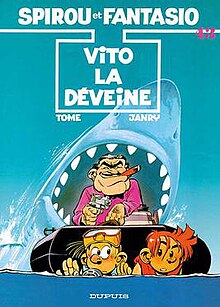

[8] It was the team of Tome (writing) and Janry (art) which was to find lasting success with Spirou, both in terms of sales and critical appeal.

), and even time travel (the diptych of L'horloger de la comète and Le réveil du Z, featuring future descendants of the Count and Zorglub).

Their position as the official Spirou authors made them the flagship team to a whole new school of young, like-minded artists, such as Didier Conrad, Bernard Hislaire, or Frank Le Gall, who had illustrious careers of their own.

In Machine qui rêve (1998), Tome and Janry tried to once again renew the series with a more mature storyline (wounded hero, love relationships, etc.

This sudden shift into a darker tone shocked many readers, although its seeds were apparent in previous Spirou albums and in other series by the same authors (Soda, Berceuse assassine).

At any rate, the controversy caused Tome and Janry to concentrate on Le Petit Spirou, and stop making albums in the main series.

Morvan and Munuera's Spirou is partly remarkable in that it uses background elements and secondary characters from the whole history of the title, and not just from Franquin's period.

Spirou and Fantasio uncover the story of two children with telekinetic powers (similarly to the manga Akira) that are forced to construct an Edo and Meiji period theme park.

[11] In January 2009, it was announced in Spirou magazine #3694 that Morvan and Munuera would be succeeded by Fabien Vehlmann and Yoann, who had together created the first volume of Une aventure de Spirou et Fantasio par.... Their first album in the regular series was announced for October 2009,[12] but was later pushed back to September 3, 2010, and is named Alerte aux zorkons.

The third, Le tombeau des Champignac, by Yann and Fabrice Tarrin, is a slightly modernized homage to Franquin's classic period.

The fourth, Journal d'un ingénu, by Emile Bravo, is a novelistic homage to the original Rob-Vel and Jijé's universes and stories, and was released to critical acclaim, being awarded at the Angoulême festival.

[17] Main and recurring Spirou et Fantasio characters: This list includes French titles, their English translation, and the first year of publication The strip has been translated to several languages, among them Spanish, Portuguese, English, Japanese[citation needed], German, Bahasa Indonesia, Vietnamese, Turkish, Italian, Dutch, Finnish, Scandinavian languages, Serbo-Croatian, Galician, Catalan,[20] Icelandic and Arabic.

[22] In 1960, Le nid des Marsupilamis was printed in the weekly British boys' magazine Knockout, under the title Dickie and Birdbath Watch the Woggle.

Spirou – Hope Against All Odds: Part 2, published June 17, 2020, ASIN B08B6C53ZV The popularity of the series has led to an adaptation of the characters into different media.

The stories were based on Le Dictateur de Champignon and Les Robinsons du Rail, with participation of Yvan Delporte and André Franquin.

A live-action movie adaptation directed by Alexandre Coffre was released in 2018,[27] starring Thomas Solivérès as Spirou, Alex Lutz as Fantasio, Christian Clavier as Count of Champignac, Géraldine Nakache as Seccotine and Ramzy Bédia as Zorglub.

[37] SPIRou (SpectroPolarimètre Infra-Rouge) is a near-infrared spectropolarimeter and high-precision velocimeter designed and constructed by an international consortium for observing exoplanets and the forming of Sun-like stars and their planets.