Fecal microbiota transplant

[8] FMT has been used experimentally to treat other gastrointestinal diseases, including colitis, constipation, irritable bowel syndrome, and neurological conditions, such as multiple sclerosis and Parkinson's.

[16] Once considered to be a "last resort therapy" by some medical professionals, due to its unusual nature and invasiveness compared with antibiotics, perceived potential risk of infection transmission, and lack of Medicare coverage for donor stool, position statements by specialists in infectious diseases and other societies[14] have been moving toward acceptance of FMT as a standard therapy for relapsing CDI and also Medicare coverage in the United States.

Published experience of ulcerative colitis treatment with FMT largely shows that multiple and recurrent infusions are required to achieve prolonged remission or cure.

[35][36] The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning against potentially life-threatening consequences of transplanting material from improperly screened donors.

[14][37][41] No laboratory standards have been agreed upon,[41] so recommendations vary for size of sample to be prepared, ranging from 30 to 100 grams (1.1 to 3.5 ounces) of fecal material for effective treatment.

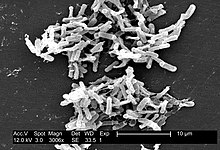

[14] One hypothesis behind fecal microbiota transplant rests on the concept of bacterial interference, i.e., using harmless bacteria to displace pathogenic organisms, such as by competitive niche exclusion.

[44] Recently, in a pilot study of five patients, sterile fecal filtrate was demonstrated to be of comparable efficacy to conventional FMT in the treatment of recurrent CDI.

[50] The first use of donor feces as a therapeutic agent for food poisoning and diarrhea was recorded in the Handbook of Emergency Medicine by a Chinese man, Hong Ge, in the 4th century.

Twelve hundred years later Ming dynasty physician Li Shizhen used "yellow soup" (aka "golden syrup") which contained fresh, dry or fermented stool to treat abdominal diseases.

[52] The consumption of "fresh, warm camel feces" has also been recommended by Bedouins as a remedy for bacterial dysentery; its efficacy, probably attributable to the antimicrobial subtilisin produced by Bacillus subtilis, was anecdotally confirmed by German soldiers of the Afrika Korps during World War II.

[54] The first use of FMT in western medicine was published in 1958 by Ben Eiseman and colleagues, a team of surgeons from Colorado, who treated four critically ill people with fulminant pseudomembranous colitis (before C. difficile was the known cause) using fecal enemas, which resulted in a rapid return to health.

In May 1988 their group treated the first ulcerative colitis patient using FMT, which resulted in complete resolution of all signs and symptoms long term.

[57] In the United States, the FDA announced in February 2013 that it would hold a public meeting entitled "Fecal Microbiota for Transplantation" which was held on May 2–3, 2013.

[61] It argued since FMT is used to prevent, treat, or cure a disease or condition, and intended to affect the structure or any function of the body, "a product for such use" would require an Investigational New Drug (IND) application.

[62] In March 2014, the FDA issued a proposed update (called "draft guidance") that, when finalized, is intended to supersede the July 2013 enforcement policy for FMT to treat C. difficile infections unresponsive to standard therapies.

[63] Some doctors and people who want to use FMT have been worried that the proposal, if finalized, would shutter the handful of stool banks which have sprung up, using anonymous donors and ship to providers hundreds of miles away.

The first safety alert, issued in June 2019, described the transmission of a multidrug resistant organism from a donor stool that resulted in the death of one person.

[71] One example is the rectal bacteriotherapy (RBT), developed by Tvede and Helms, containing 12 individually cultured strains of anaerobic and aerobic bacteria originating from healthy human faeces.

[73] Elephants, hippos, koalas, and pandas are born with sterile intestines, and to digest vegetation need bacteria which they obtain by eating their mothers' feces, a practice termed coprophagia.