Ferdinand Lee Barnett (Chicago)

Ferdinand Lee Barnett (February 18, 1852 – March 11, 1936) was an American journalist, lawyer, and civil rights activist in Chicago, beginning in the late Reconstruction era.

Born in Nashville, Tennessee, during his childhood, his African-American family fled to Windsor, Ontario, Canada, just before the American Civil War.

The Barnett family returned to the US in 1869 after the American Civil War and the end of slavery, settling in Chicago, Illinois.

[8] In December 1877, Barnett, along with co-editors Abram T. Hall, Jr. and James E. Henderson, organized the semi-monthly newspaper, the Conservator, the first edition appearing on January 1, 1878.

)[11] The Conservator was a radical journal that focused on justice and equal rights, and Barnett was soon recognized as a local black leader.

He was selected as a delegate to the May 1879 National Conference of Colored Men in Nashville, where he gave a noted speech calling for unity and education.

[2] He was a delegate to the 1884 Inter-State Conference of Colored Men in Pittsburgh,[12] and the national convention of the Timothy Thomas Fortune led Afro-American League in Chicago in 1890 where he was named secretary.

The act sparked a national outcry and Barnett took part in meetings in Chicago called to organize reaction.

At a meeting of one thousand people at Bethel A. M. E. Church, Reverend W. Gaines' call for the crowd to sing the then de facto national anthem, "My Country, 'Tis of Thee", was refused, one member of the audience declaring: "I don't want to sing that song until this country is what it claims to be, 'sweet land of liberty'.

Barnett closed the meeting appealing for a calm and careful response, but also expressing great frustration and concern that the violence against blacks may one day lead to reprisals.

It had been claimed that lynching, while not legal, was a natural result of the need for revenge of a community against perpetrators of violent crime and did not single out blacks.

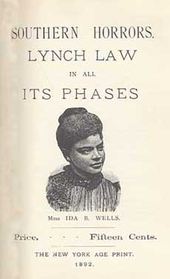

[2] The pamphlet was published by Barnett, Wells, abolitionist Frederick Douglass, and educator Irvine Garland Penn.

It also included blacks in white exhibits, such as Nancy Green's portrayal of the character "Aunt Jemima" for the R. T. Davis Milling Company.

[22] The younger Ferdinand Barnett served as Eighth Regiment supply sergeant in World War I.

[2] Barnett's attraction to Wells included his recognition of the mutual support for each other's careers that the relationship would bring.

[2] As assistant state's attorney, Barnett worked in the juvenile court, in antitrust cases, and in habeas corpus and extradition proceedings.

[2] In 1902, Barnett made national news when he suggested that 10 million blacks would revolt against lynch law in the South at a gathering at Bethlehem Church in Chicago.

[2]In 1906, Barnett was nominated as a judge in the new Municipal Court of Chicago, the first black candidate for a judgeship in Illinois.

Although Campbell was convicted for the murder of Odelle B. Allen, his death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment by Governor Frank O. Lowden on April 12, 1918.