Batok

[6][12] These terms were also applied to identical designs used in woven textiles, pottery, and decorations for shields, tool and weapon handles, musical instruments, and others.

[2][3][11] Affixed forms of these words were used to describe tattooed people, often as a synonym for "renowned/skilled person"; like Tagalog batikan, Visayan binatakan, and Ilocano burikan.

The needles created wounds on the skin that were then rubbed with the ink made from soot or ashes mixed with water, oil, plant extracts (like sugarcane juice), or even pig bile.

[3][2][13] Ancient clay human figurines found in archaeological sites in the Batanes Islands, around 2500 to 3000 years old, have simplified stamped-circle patterns which clearly represent tattoos.

[18] Excavations at the Arku Cave burial site in Cagayan Province in northern Luzon have also yielded both chisel and serrated-type heads of possible hafted bone tattoo instruments alongside Austronesian material culture markers like adzes, spindle whorls, barkcloth beaters, and lingling-o jade ornaments.

[19][13][20][21] Ancient tattoos can also be found among mummified remains of various Cordilleran peoples in cave and hanging coffin burials in northern Luzon, with the oldest surviving examples of which going back to the 13th century.

[26] Tattooing was a religious experience among the Cordilleran peoples, involving direct participation of the anito spirits who are attracted to the flowing blood during the process.

A few elders of the Bontoc and Kalinga people retain tattoos up to today; but they are believed to be extinct among the Kankanaey, Apayao, Ibaloi, and other Cordilleran ethnic groups.

The most prominent tattoo is called the andori, which features geometric shapes (like chevrons, zigzags, lines, diamonds, and triangles) that start from the wrist up to the arms and the shoulders.

In addition, figurative designs are also commonly used, including those depicting centipedes, ferns, rice heavy with grain (pang ti'i), lightning, and the stairs of a traditional house.

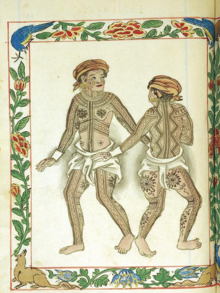

[4] The tattoos usually covered the chest, back, sides of the stomach, buttocks, arms, shoulders, hands, fingers, neck, throat, face, and legs among men.

The animals and plants depicted included centipedes (kamajan), snakes (oleg), lizards (batingal or karat), dogs (aso), and deer (olsa), among others.

Other designs included stars (talaw), carabaos (nuang), jawbones (pad-padanga), rice mortars (pinat-pattu), basket weave (inak-akbu), zigzags (tiniktiku or batikua), seeds (pinak-paksey), and rivers (balenay).

While an ever-present design, the to-o, which depicted a small human figure with the arms and legs bent outwards at the elbows and knees, represented humankind in the material world.

[36][16] Common tattoo motifs include centipedes (gayaman), centipede legs (tiniktiku), snakes (tabwhad), snakeskin (tinulipao), hexagonal shapes representing snake belly scales (chillag), coiled snakes (inong-oo), rain (inud-uchan), various fern designs (inam-am, inalapat, and nilawhat), fruits (binunga), parallel lines (chuyos), alternating lines (sinagkikao), hourglass shapes representing day and night (tinatalaaw), rice mortars (lusong), pig's hind legs (tibul), rice bundles (sinwhuto or panyat), criss-crossing designs (sina-sao), ladders (inar-archan), eagles (tulayan), frogs (tokak), and axe blades (sinawit).

Murder was considered wrong in Kalinga society, but the killing of an enemy was seen as noble act, and part of the nakem (sense of responsibility) by warriors for the protection of the entire village.

A boy can only acquire tattoos after participating in a successful headhunting expedition (kayaw) or inter-village warfare (baraknit), even if they did not personally take part in the kill.

During pre-colonial times, people without tattoos were known as dinuras (or chinur-as in Butbut Kalinga) and were teased as cowards and bad omens for the community.

[16][30][31] The ink is traditionally made from powdered charcoal or soot from cooking pots mixed with water in a half coconut shell and thickened with starchy tubers.

They are applied to the skin using an instrument known as the gisi (also kisi), these can either be citrus thorns inserted at a right angle to a stick, or a carabao horn bent with heat with a cluster of metal needles at the tip.

In Manobo mythology, Ologasi is depicted as an antagonist and a guardian of the gate to the spirit world (Somolaw) where the souls of the dead travel to by boat.

Some male practitioners exist but are restricted to tattooing other men, as touching the body of a woman who is not a relative or their spouse is regarded as socially inappropriate in Manobo culture.

[6] Mangotoeb are traditionally offered gifts by the recipient before the tattooing process, usually beads (baliog), fiber leglets (tikos), and food.

During the healing process, the wounds are rubbed with heated nodules of an epiphyte called kagopkop, which soothes the itching and supposedly keeps the tattoo color dark.

The first Spanish name for the Visayans, Los Pintados ("The Painted Ones") was a reference to the tattooed people particularly of Samar, Leyte, Mindanao, Bohol, and Cebu, whom were the first of such encountered by the Magellan expedition in the Philippine islands.

It was expected of adults to have them, with the exception of asog (feminized men, usually shamans) for whom it was socially acceptable to be mapuraw or puraw (unmarked, compare with Samoan pulaʻu).

Elite warriors also often had frightening mask-like facial tattoos on chin and face (reaching up to the eyelids) called bangut or langi meant to resemble crocodile jaws or raptorial beaks, among others.

[3][49] The rulers of the Rajahnate of Butuan and the region of Surigao (pre-colonial Karaga) were among the first "painted" (tattooed) Filipinos encounted by the Magellan expedition and described by Antonio Pigafetta.

[50][51] A 17th century illustration from the Dutch pirate Olivier van Noort depicts an Abaknon man from the island of Capul covered in tattoos.

Tagalog tattooing traditions might have persisted on the island of Marinduque as recorded by the Spanish conquistador Miguel de Loarca (c. 1582-1583), who described the locals as "pintados" not under the jurisdiction of Cebu, Arevalo (Panay), or Camarines (Bicol Region).