Fire-setting

Some experiments have suggested that the water (or any other liquid) did not have a noticeable effect on the rock, but rather helped the miners' progress by quickly cooling down the area after the fire.

[3] The oldest traces of this method in Europe were found in southern France (département of Hérault) and date back to the Copper Age.

[5] Numerous finds exist from the Bronze Age, such as in the Alps, in the former mining district of Schwaz-Brixlegg in Tyrol,[6][7] or in the Goleen area in Cork,[8] to name a few.

In another part of the mine, there are three adits at different heights which have been driven through barren rock to the gold-bearing veins for some considerable distance, and they would have provided drainage as well as ventilation to remove the smoke and hot gases during a fire-setting operation.

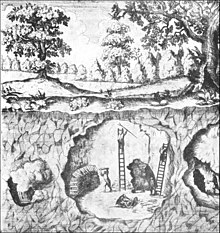

[9] The method continued in use in the medieval period, and is described by Georg Agricola in his treatise on mining and mineral extraction, De re metallica.

He warns about the problem of the "foetid vapours" and the need to evacuate the workings while the fires are lit, and presumably for some time afterwards until the gases and smoke had cleared.

Agricola mentions the use of large water-powered bellows to create a draught, and continuity of workings to the surface were essential for a stream of air to run through them.