Hannibal

In his first few years in Italy, as the leader of a Carthaginian and partially Celtic army, he won a succession of victories at the Battle of Ticinus, Trebia, Lake Trasimene, and Cannae, inflicting heavy losses on the Romans.

It is a combination of the common Phoenician masculine given name Hanno with the Northwest Semitic Canaanite deity Baal (lit, "lord") a major god of the Carthaginians ancestral homeland of Phoenicia in Western Asia.

Barca is cognate with similar names for lightning found among the Israelites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Arameans, Arabs, Amorites, Moabites, Edomites and other fellow Asiatic Semitic peoples.

Carthage at the time was in such a poor state that it lacked a navy able to transport his army; instead, Hamilcar had to march his forces across Numidia towards the Pillars of Hercules and then cross the Strait of Gibraltar.

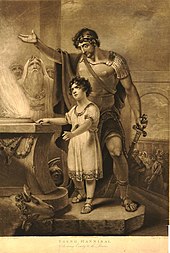

The Roman scholar Livy gives a depiction of the young Carthaginian: "No sooner had he arrived...the old soldiers fancied they saw Hamilcar in his youth given back to them; the same bright look; the same fire in his eye, the same trick of countenance and features.

[25] In his first campaign, Hannibal attacked and stormed the Olcades' strongest centre, Alithia, which promptly led to their surrender, and brought Punic power close to the River Tagus.

On his return home, laden with many spoils, a coalition of Spanish tribes, led by the Carpetani, attacked, and Hannibal won his first major battlefield success and showed off his tactical skills at the battle of the River Tagus.

Starting in the spring of 218 BC, he crossed the Pyrenees and, by conciliating the Gaulish chiefs along his passage before the Romans could take any measures to bar his advance, was able to reach the Rhône by September.

Mahaney et al. argue that factors used by De Beer to support Col de la Traversette including "gauging ancient place names against modern, close scrutiny of times of flood in major rivers and distant viewing of the Po plains" taken together with "massive radiocarbon and microbiological and parasitical evidence" from the alluvial sediments either side of the pass furnish "supporting evidence, proof if you will" that Hannibal's invasion went that way.

Even before news of the defeat at Ticinus had reached Rome, the Senate had ordered Consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus to bring his army back from Sicily to meet Scipio and face Hannibal.

There Hannibal had an opportunity to show his masterful military skill at the Trebia in December of the same year, after wearing down the superior Roman infantry, when he cut it to pieces with a surprise attack and ambush from the flanks.

Hannibal marched boldly around Flaminius' left flank, unable to draw him into battle by mere devastation, and effectively cut him off from Rome, executing the first recorded turning movement in military history.

In the meantime, the Romans hoped to gain success through sheer strength and weight of numbers, and they raised a new army of unprecedented size, estimated by some to be as large as 100,000 men, but more likely around 50,000–80,000.

[56] After Cannae, the Romans were very hesitant to confront Hannibal in pitched battle, preferring instead to weaken him by attrition, relying on their advantages of interior lines, supply, and manpower.

[58] As Polybius notes, "How much more serious was the defeat of Cannae, than those that preceded it can be seen by the behaviour of Rome's allies; before that fateful day, their loyalty remained unshaken, now it began to waver for the simple reason that they despaired of Roman Power.

Instead, he had to content himself with subduing the fortresses that still held out against him, and the only other notable event of 216 BC was the defection of certain Italian territories, including Capua, the second largest city of Italy, which Hannibal made his new base.

However, Hannibal slowly began losing ground—inadequately supported by his Italian allies, abandoned by his government, either because of jealousy or simply because Carthage was overstretched, and unable to match Rome's resources.

Although the ageing Hannibal was suffering from mental exhaustion and deteriorating health after years of campaigning in Italy, the Carthaginians still had the advantage in numbers and were boosted by the presence of 80 war elephants.

[65] After an audit confirmed Carthage had the resources to pay the indemnity without increasing taxation, Hannibal initiated a reorganization of state finances aimed at eliminating corruption and recovering embezzled funds.

Although Phoenician territories like Tyre and Sidon possessed the necessary combination of raw materials, technical expertise, and experienced personnel, it took much longer than expected for it to be completed, most likely due to wartime shortages.

[75] The ensuing Battle of Myonessus resulted in a Roman-Rhodian victory, which cemented Roman control over the Aegean Sea, enabling them to launch an invasion of Seleucid Asia Minor.

[76] The truce was signed at Sardes in January 189 BC, whereupon Antiochus agreed to abandon his claims on all lands west of the Taurus Mountains, paid a heavy war indemnity and promised to hand over Hannibal and other notable enemies of Rome from among his allies.

[78] Suspicious that Antiochus was prepared to surrender him to the Romans, Hannibal fled to Crete, but he soon went back to Anatolia and sought refuge with Prusias I of Bithynia, who was engaged in warfare with Rome's ally, King Eumenes II of Pergamon.

[82] Cornelius Nepos[83] and Livy,[84] tell a different story, namely that the ex-consul Titus Quinctius Flamininus, on discovering that Hannibal was in Bithynia, went there in an embassy to demand his surrender from King Prusias.

When Hannibal's successes had brought about the death of two Roman consuls, he vainly searched for the body of Gaius Flaminius on the shores of Lake Trasimene, held ceremonial rituals in recognition of Lucius Aemilius Paullus, and sent Marcellus' ashes back to his family in Rome.

Ronald Mellor considered the Greek scholar a loyal partisan of Scipio Aemilianus,[106] while H. Ormerod does not view him as an "altogether unprejudiced witness" when it came to his pet peeves, the Aetolians, the Carthaginians, and the Cretans.

According to Appian, several years after the Second Punic War, Hannibal served as a political advisor in the Seleucid Kingdom and Scipio arrived there on a diplomatic mission from Rome.

[113] According to Polybius 23, 13, p. 423: It is a remarkable and very cogent proof of Hannibal's having been by nature a real leader and far superior to anyone else in statesmanship, that though he spent seventeen years in the field, passed through so many barbarous countries, and employed to aid him in desperate and extraordinary enterprises numbers of men of different nations and languages, no one ever dreamt of conspiring against him, nor was he ever deserted by those who had once joined him or submitted to him.Count Alfred von Schlieffen developed his "Schlieffen Plan" (1905/1906) from his military studies, including the envelopment technique that Hannibal employed in the Battle of Cannae.

That war could be waged by avoiding in lieu of seeking battle; that the results of a victory could be earned by attacks upon the enemy's communications, by flank-manoeuvres, by seizing positions from which safely to threaten him in case he moved, and by other devices of strategy, was not understood... [However,] for the first time in the history of war, we see two contending generals avoiding each other, occupying impregnable camps on heights, marching about each other's flanks to seize cities or supplies in their rear, harassing each other with small-war, and rarely venturing on a battle which might prove a fatal disaster—all with a well-conceived purpose of placing his opponent at a strategic disadvantage... That it did so was due to the teaching of Hannibal.

Tunisia's home and away kit for the 2022 FIFA World Cup was inspired by the Ksour Essef cuirass, a piece of body armor believed to be worn by Carthaginian soldiers under the command of Hannibal.

From the Department of History, United States Military Academy