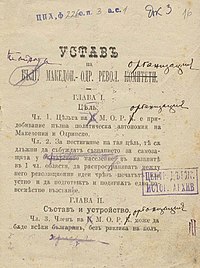

First statute of the IMRO

[11] Certain contradictions and even mutually exclusive statements, along with inconsistencies exist in the testimonies of the founding and other early members of the Organization, which further complicates the solution of the problem.

[19] They were native to the region of Macedonia, and some of them were influenced from anarcho-socialist ideas, which gave to organisation's basic documents slightly leftist leaning.

The occasion for convening this meeting was the celebration on the consecration of the newly built Bulgarian Exarchate church in the town in August 1894.

Schoolteachers were en masse involved in the committee's activity, and the Ottoman authorities considered the Bulgarian schools then "nests of bandits".

[26] In the earliest dated samples of statutes and regulations of the Organization discovered so far, it is called Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Committees (BMARC).

[note 1][27][28][29] These documents refer to the then Bulgarian population in the Ottoman Empire, which was to be prepared for a general uprising in Macedonia and Adrianople regions, aiming to achieve political autonomy for them.

[34] This ethnic restriction matches with the memoirs of some founding and ordinary members, where is mentioned such a requirement, set only in the Organization's first statute.

[35][note 2] The name of BMARC, as well as information about its statute, was mentioned in the foreign press of that time, in Bulgarian diplomatic correspondence, and exists in the memories of some revolutionaries and contemporaries.

[36] Contradictions, inconsistencies and even mutually exclusive statements exist in the testimonies of the founding and other early members of the Organization on the issue.

[note 3] On the other hand, according to the founding member Gyorche Petrov, initially the IMRO was not called an "Organization", and this term was introduced after 1895.

[41][42] However, per Hristo Kotsev [bg] (1869-1933) Dame Gruev commissioned him to start the construction of the committee network in Adrianople region in 1895.

According to Gyurov's claims, he had hidden one copy each of the statutes and regulations, but he did not manage to keep them because they fell apart due to poor storage conditions.

It is known that the first statute was prepared by Petar Poparsov and was adopted at the beginning of 1894, and according to some reports, the first regulations were developed by Ivan Hadzhinikolov either in the same year or in 1895.

Per Iliya Doktorov [bg] (1876-1947) initially the organization had a nationalist character and only Bulgarians had the right to be members of it, but this ethnic restriction lasted until 1896.

According to Nikola Zografov in 1895 Gotse Delchev was supplied with a power of attorney from the name of the BMARC and sent to Sofia to propagate the struggle for autonomy that was open to every Bulgarian.

[62][63] In 1961, Macedonian historian Ivan Katardžiev published undated statute and regulations discovered by him, naming the organization BMARC, which he dated from 1894.

[72] Per Gane Todorovski from its very name could be concluded this was initially an organization primarily of the Bulgarian population in Macedonia and Adrianople areas.

Later that conclusion was confirmed, while corrected statute and rules of the BMARC were discovered in Bulgaria, which are practically drafts of the basic documents of the SMARO.

[85] However in 2021, he has rejected all this, claiming that allegedly not a single document written from any activist of the Organization has been found so far, containing the name of BMARC.

[107] Other Bulgarian historians do not accept the view of Pandev and continue to adhere to that of Katardziev, i.e., the first statutory name of the organization from 1894 was BMARC.

[122] On October 10, 1900, the newspaper "Pester Lloyd", published in retelling form excerpts from the captured by the Ottoman authorities statutes of the Bulgarian Macedonian Revolutionary Committee, i.e. BMARC.

[36] On the other hand, the Austro-Hungarian consul in Skopje Gottlieb Para [bg] (1861-1915), in his report of 14.11.1902, attached a document in translation, which he designated as the new statute of the revolutionary organization.

[123] At the same time the Serbian Consul General in Bitola Mihajlo Ristic wrote on January 25, 1903 that until the beginning of 1902, the work of the Committee had a purely Bulgarian character, while the local Serbs and Greeks were feared from its activity.

[124] Also, even in 1895, Gotse Delchev was supplied with a power of attorney and sent to Sofia, as a representative of the "Bulgarian Central Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Committee".

According to the memoires of Dimitar Voynikov (1896-1990), when Delchev visited Strandzha Mountain in 1900, the changes in the statute of SMARO were already fact and were discussed at a meetings with the local IMRO-activists, where his father was present.

[131] Per Article 3 of the statute of BMARC: "Membership is open to any Bulgarian, irrespective of sex, who has not compromised himself in the eyes of the community by dishonest and immoral actions, and who promises to be of service in some way to the revolutionary cause of liberation.

While this leftist idea was taken aboard by some Vlachs, as well as by some Patriarchist Slavic-speakers,[note 4] it failed to attract other groups for whom the IMRO remained the Bulgarian Committee.

[135][136][137] According to Hristo Tatarchev, founders' demand for autonomy was motivated by concerns that a direct unification with Bulgaria would provoke the rest of the Balkan states and the Great Powers to military actions.

Among its founders were scientists, historians, journalists and descendants of Bulgarian historical figures from the regions of Macedonia and Southern Thrace.

In North Macedonia, the acknowledgement of any Bulgarian influence on its history and politics is very undesirable, because it contradicts the post-WWII Yugoslav Macedonian nation-building and historical narratives, based on a deeply anti-Bulgarian attitudes, which still continue today.

Statute of the Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees

Chapter I. – Goal

Art. 1. The goal of BMARC is to secure full political autonomy for the Macedonia and Adrianople regions .

Art. 2. To achieve this goal they [the committees] shall raise the awareness of self-defense in the Bulgarian population in the regions mentioned in Art. 1., disseminate revolutionary ideas – printed or verbal, and prepare and carry on a general uprising.

Chapter II. – Structure and Organization

Art. 3. A member of BMARC can be any Bulgarian, independent of gender, ...