Foibe massacres

[16][22][23] Other historians dispute this, stating that Italians were not targeted for their ethnicity,[24][2][3][4] that the majority of victims were members of fascist military and police forces,[16][25][7] and that many more Slavic collaborators were killed in postwar reprisals.

In Italy the term foibe has, for some authors and scholars,[b] taken on a symbolic meaning; for them it refers in a broader sense to all the disappearances or killings of Italian people in the territories occupied by Yugoslav forces.

According to author Raoul Pupo [it]:[32] It is well known that the majority of the victims didn't end their lives in a Karst cave, but met their deaths on the road to deportation, as well as in jails or in Yugoslav concentration camps.

[c] The terror spread by these disappearances and killings eventually caused the majority of the Italians of Istria, Fiume, and Zara to flee to other parts of Italy or the Free Territory of Trieste.

In the middle of the 6th and the beginning of the 7th century began the Slavic migration, which caused the Romance-speaking population, descendants of Romans and Illyrians (speaking Dalmatian), to flee to the coast and islands.

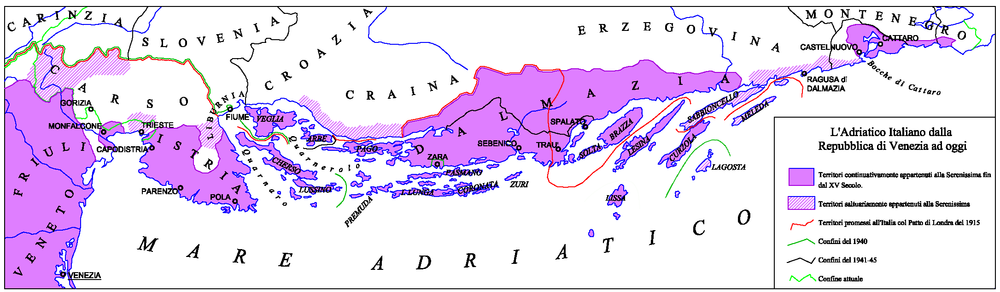

[61] Republic of Venice influenced the neolatins of Istria and Dalmatia until 1797, when it was conquered by Napoleon: Capodistria and Pola were important centers of art and culture during the Italian Renaissance.

[65] However, after the Third Italian War of Independence (1866), when the Veneto and Friuli regions were ceded by the Austrians to the newly formed Kingdom Italy, Istria and Dalmatia remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, together with other Italian-speaking areas on the eastern Adriatic.

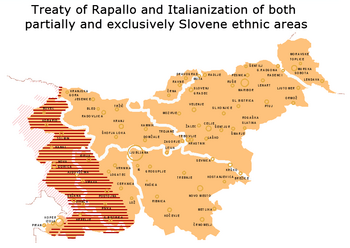

[66] During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria outlined a wide-ranging project aimed at the Germanization or Slavization of the areas of the empire with an Italian presence:[67] His Majesty expressed the precise order that action be taken decisively against the influence of the Italian elements still present in some regions of the Crown and, appropriately occupying the posts of public, judicial, masters employees as well as with the influence of the press, work in South Tyrol, Dalmatia and Littoral for the Germanization and Slavization of these territories according to the circumstances, with energy and without any regard.

[74] Bartoli's evaluation was followed by other claims that Auguste de Marmont, the French Governor General of the Napoleonic Illyrian Provinces commissioned a census in 1809 which found that Dalmatian Italians comprised 29% of the total population of Dalmatia.

Pula, for example, was badly affected by the drastic dismantling of its massive Austrian military and bureaucratic apparatus of more than 20,000 soldiers and security forces, as well as the dismissal of the employees from its naval shipyard.

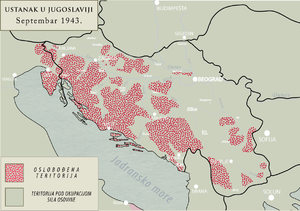

The Nazis, aided by Italian and Slav collaborators, launched brutal anti-Partisan campaigns, with mass killings of civilians (e.g. the Lipa massacre),[97][98] yet more were sent to concentration camps.

Toward the end of the war, the local CLN focused its efforts on retaining Istria, the Slovene Littoral, Trieste, Gorizia, Rijeka and Zadar for Italy,[4] while accepting members of fascist and Nazi-collaborationist forces into its ranks.

[11][45] While the foibe became the symbol of these massacres, only a minority of the victims were killed with this method, largely during the first wave; a far larger part were executed and buried in mass graves or died in Yugoslav prisons and concentration camps.

[102][103] After the re-occupation of Istria by Axis forces in September 1943, following the first wave of killings, the fire brigade of Pola, under the command of Arnaldo Harzarich, recovered 204 bodies from the foibe of the region.

Alongside a large number of Fascists, however, among those killed were also anti-Fascists who opposed the Yugoslav annexation of the region, such as Socialist Licurgo Olivi and Action Party leader Augusto Sverzutti, members of the Committee of National Liberation of Gorizia; in Trieste, the same fate befell Resistance leaders Romano Meneghello (posthumously awarded a Silver Medal of Military Valor for his Resistance activities) and Carlo Dell'Antonio.

In Fiume (where at least 652 Italians were killed or disappeared between 3 May 1945 and 31 December 1947, according to a joint Italian-Croat study), Autonomist Party leaders Mario Blasich, Joseph Sincich and Nevio Skull were among those executed by the Yugoslavs soon after the occupation, as was anti-Fascist and Dachau survivor Angelo Adam.

[121] Due to claims of hundreds having been killed and tossed into the Basovizza mineshaft, in August–October 1945 British military authorities investigated the shaft, ultimately recovering 9 German soldiers, 1 civilian and a few horse cadavers.

Despite repeat demands from various right-wing groups to further excavate the shaft,[123] the government of Trieste, led by the Christian Democratic mayor Gianni Bartoli, declined to do so, claiming among other reasons, lack of financial resources.

[126] In 1993 a study titled Pola Istria Fiume 1943–1945[128] by Gaetano La Perna provided a detailed list of the victims of Yugoslav occupation (in September–October 1943 and from 1944 to the very end of the Italian presence in its former provinces) in the area.

Pupo claims that the primary targets of the purges were repressive forces of the Fascist regime, and civilians associated with the regime, including Slavic collaborators, thus:With regard to the civilian population of Venezia Giulia the Yugoslav troops did not behave at all like an army occupying enemy territory: nothing in their actions recalls the indiscriminate violence of Red Army soldiers in Germany, on the contrary, their discipline seems in some ways superior even to that of the Anglo-American units.

[d]Since Yugoslav troops did not behave like an occupying army,[e] this partly contradicts the numerous academic authors and institutional figures — both in Italy and abroad — who recognized an ethnic cleansing against Italians.

According to Fogar and Miccoli there is the need to put the episodes in 1943 and 1945 within [the context of] a longer history of abuse and violence, which began with Fascism and with its policy of oppression of the minority Slovenes and Croats and continued with the Italian aggression on Yugoslavia, which culminated with the horrors of the Nazi-Fascist repression against the Partisan movement.

Evocations of the 'Slav other' and of the terrors of the foibe made by state institutions, academics, amateur historians, journalists, and the memorial landscape of everyday life were the backdrop to the post-war renegotiation of Italian national identity.

These events were triggered by the atmosphere of settling accounts with the fascist violence; but, as it seems, they mostly proceeded from a preliminary plan which included several tendencies: endeavours to remove persons and structures who were in one way or another (regardless of their personal responsibility) linked with Fascism, with Nazi supremacy, with collaboration and with the Italian state, and endeavours to carry out preventive cleansing of real, potential or only alleged opponents of the communist regime, and the annexation of the Julian March to the new Yugoslavia.

[4] The foibe have been a neglected subject in mainstream political debate in Italy, Yugoslavia and former-Yugoslav nations, only recently garnering attention with the publication of several books and historical studies.

The Italian Parliament (with the support of the vast majority of the represented parties) made 10 February National Memorial Day of the Exiles and Foibe, first celebrated in 2005 with exhibitions and observances throughout Italy (especially in Trieste).

Nowadays, a large part of the Italian left acknowledges the nature of the foibe massacres, as attested by some declarations of Luigi Malabarba, senator for the Communist Refoundation Party, during the parliamentary debate on the institution of the National Memorial Day:[142]In 1945 there was a ruthless policy of exterminating opponents.

The war, which had begun as anti-fascist, became anti-German and anti-Italian.Italian president Giorgio Napolitano took an official speech during celebration of the "Memorial Day of Foibe Massacres and Istrian-Dalmatian exodus" in which he stated:[143] ... already in the unleashing of the first wave of blind and extreme violence in those lands, in the autumn of 1943, summary and tumultuous justicialism, nationalist paroxysm, social retaliation and a plan to eradicate Italian presence intertwined in what was, and ceased to be, the Julian March.

What we can say for sure is that what was achieved – in the most evident way through the inhuman ferocity of the foibe – was one of the barbarities of the past century.The Croatian President Stipe Mesić immediately responded in writing, stating that: It was impossible not to see overt elements of racism, historical revisionism and a desire for political revenge in Napolitano's words.

The explanations were accepted with understanding and they have contributed to overcoming misunderstandings caused by the speech.In Italy, Law 92 of 30 March 2004[148] declared 10 February as a Day of Remembrance dedicated to the memory of the victims of Foibe and the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus.