Fokker Scourge

[4] Use of the term coincided with a political campaign to end a perceived dominance of the Royal Aircraft Factory in the supply of aircraft to the Royal Flying Corps, a campaign that was begun by the pioneering aviation journalist C. G. Grey and Noel Pemberton Billing M.P., founder of Pemberton-Billing Ltd (Supermarine from 1916) and a great enthusiast for aerial warfare.

[5] As aerial warfare developed, the Allies gained a lead over the Germans by introducing machine-gun armed types such as the Vickers F.B.5 Gunbus fighter and the Morane-Saulnier L.[6][7] By early 1915, the German Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL, Supreme Army Command) had ordered the development of machine-gun-armed aircraft to counter those of the Allies.

Saulnier had failed to develop a synchroniser and with Garros, as an interim solution, fitted metal wedges to the propeller; bullets that hit the blades were deflected by them.

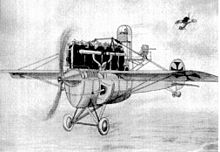

Impulses from a cam driven by the engine controlled the timing of the machine-gun for its fire to be limited to the intervals between the propeller blades' travel past the barrel.

[13] Among several pre-war patents for similar devices was that of Franz Schneider, a Swiss engineer who had worked for Nieuport and the German LVG company.

[15][16] Fokker demonstrated A.16/15 in May and June 1915 to German fighter pilots, including Kurt Wintgens, Oswald Boelcke and Max Immelmann.

[24] M.5K/MG prototype airframe E.3/15, the first Eindecker delivered to FFA 62, was armed with a Parabellum MG14 gun, synchronised by the unreliable first version of the Fokker gear.

At first, E.3/15 was jointly allocated to him and Immelmann when their "official" duties permitted, allowing them to master the type's difficult handling characteristics and to practice shooting at ground targets.

[22] After about ten minutes of manoeuvring (giving the lie to exaggerated accounts of the stability of B.E.2 aircraft) Immelmann had fired 450 rounds, which riddled the B.E.

[31] The mystique acquired by the Fokker was greater than its material effect and in October, RFC HQ expressed concern at the willingness of pilots to avoid combat.

RFC losses were exacerbated by the increase in the number of aircraft at the front, from 85 to 161 between March and September, the hard winter of 1915–1916 and some aggressive flying by the new German "C" type two-seaters.

[39] On 7 February, on a II Wing long-range reconnaissance, the observation pilot flew at 7,500 ft (2,300 m); a German aircraft appeared over Roulers (Roeselare) and seven more closed in behind the formation.

The flight was cancelled due to bad weather but twelve escorts for one reconnaissance aircraft demonstrated the effect of the Fokkers in reducing the efficiency of RFC operations.

[41] British and French reconnaissance flights to get aerial photographs for intelligence and artillery ranging data had become riskier, in spite of German fighters being forbidden to fly over Allied lines (to keep the synchronisation gear secret).

[42] This policy, for various reasons, prevailed for most of the war; the rarity of German fighters appearing behind the Allied lines limited the degree of air superiority they were able to attain.

Organised in specialist fighter squadrons (escadrilles de chasse) the Nieuports could operate in formations larger than the singletons or pairs normally flown by the Fokkers, quickly regaining air superiority for the Aéronautique Militaire.

This aircraft had a modest performance but its superior manoeuvrability gave it an advantage over the Eindecker, especially once the Lewis gun was fixed to point in the direction of flight.

[52] Idflieg was sufficiently desperate to order German firms to build Nieuport copies, of which the Euler D.I and the Siemens-Schuckert D.I were built in small numbers.

By July 1916, KEK had been formed at Vaux, Avillers, Jametz and Cunel near Verdun as well as other places on the Western Front, as Luftwachtdienst (aerial guard service) units, consisting only of fighters.

[58] Among British politicians and journalists who grossly exaggerated the material effects of the "Scourge" were the eminent pioneering aviation journalist C. G. Grey, founder of The Aeroplane, one of the first aviation magazines and Noel Pemberton Billing, a Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) pilot, notably unsuccessful aircraft designer and manufacturer and a Member of Parliament from March 1916.

When the news of the Fokker monoplane fighters reached him in late 1915, Grey was quick to blame the problem on orders for equipment that the latest developments had rendered obsolete.

[62] In the next two years, the Allied air forces gradually overwhelmed the Luftstreitkräfte in quality and quantity, until the Germans were only able to gain temporary control over small areas of the Western Front.