Foreign relations of imperial China

During the 2nd century BC, Zhang Qian became the first known Chinese diplomat to venture deep into Central Asia in search of allies against the Mongolic Xiongnu confederation.

Buddhism from India was introduced to China during the Eastern Han period and would spread to neighboring Vietnam, Korea, and Japan, all of which would adopt similar Confucian cultures based on the Chinese model.

The Mongol Empire became the dominant state in Asia, and the Pax Mongolica encouraged trade of goods, ideas, and technologies from east to west during the early and mid-13th century.

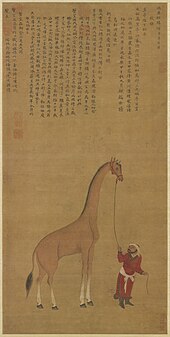

As representatives of the Yongle Emperor, Zheng's fleet sailed throughout Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean and to East Africa exacting tribute, granting lavish gifts to vassal states, and even invaded Sri Lanka.

However, the fleet was later dismantled and the Ming emperors thereafter fostered Haijin isolationist policies that limited international trade and foreign contacts to a handful of seaports and other locations.

Catholic Jesuit missions in China were also introduced, with Matteo Ricci being the first European allowed to enter the Forbidden City of the Ming emperors in Beijing.

During the subsequent Qing dynasty Jesuits from Europe such as Giuseppe Castiglione gained favor at court until the Chinese Rites controversy and most missionaries were expelled in 1706.

The British Macartney Embassy of 1793 failed to convince the Qianlong Emperor to open northern Chinese ports for foreign trade or establish direct relations.

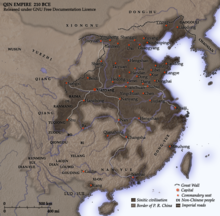

Theoretically, the lands around the imperial capital were regarded as "five zones of submission", - the circular areas differentiated according to the strength of the benevolent influence from the Son of Heaven.

During the 2nd century BC, the Chinese had sailed past Southeast Asia and into the Indian Ocean, reaching India and Sri Lanka by sea before the Romans.

Emperor Ming establishing the White Horse Temple in the 1st century AD is demarcated by the 6th-century Chinese writer Yang Xuanzhi as the official introduction of Buddhism to China.

[1] Although introduced during the Han dynasty, the chaotic, divisionary Period of Disunity (220–589) saw a flourishing of Buddhism and travels to foreign regions inspired by Buddhist missionaries.

The triple schism of China into three warring states made engaging in costly conflict a necessity, so they could not heavily commit themselves to issues and concerns of traveling abroad.

This allowed for sinicized Xiongnu nomads to capture both of China's historical capitals at Luoyang and Chang'an, forcing the remnants of the Jin court to flee south to Jiankang (present-day Nanjing).

One of the diplomatic highlights of this short-lived dynastic period was Prince Shōtoku's Japanese embassy to China led by Ono no Imoko in AD 607.

The Tang dynasty (618–907) represents another high point for China in terms of its military might, conquest and establishment of vassals and tributaries, foreign trade, and its central political position and preeminent cultural status in East Asia.

The introduction of Islam in China began during the reign of Emperor Gaozong (r. 649–683), with missionaries such as Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas, a maternal uncle of Muhammad.

He instigated the An Lushan Rebellion, which caused the deaths of millions of people, cost the Tang dynasty their Central Asian possessions, and allowed the Tibetans to invade China and temporarily occupy the capital, Chang'an.

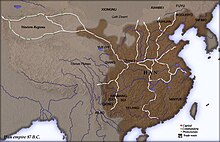

The Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) of China was the easternmost part of the vast Mongol Empire (stretching from East Asia to Eastern Europe), which became politically separated into four khanates beginning with the succession war in 1260.

Kublai was an ambitious leader who used ethnic Korean, Han, and Mongol troops to invade Japan on two separate occasions, yet both campaigns were ultimately failures.

It was during the early years of Kublai Khan's reign that Marco Polo (1254–1324) visited China, presumably as far as the previous Song capital at Hangzhou, which he described with a great deal of admiration for its scenic beauty.

The Hongwu Emperor allowed foreign envoys to visit the capitals at Nanjing and Beijing, but enacted strict legal prohibitions of private maritime trade by Chinese merchants wishing to travel abroad.

Both the Chinese envoy to Samarkand and Herat, Chen Cheng, and his opposite party, Ghiyāth al-dīn Naqqāsh, left detailed accounts of their visits to each other's country.

The greatest diplomatic highlights of the Ming period were the enormous maritime tributary missions and expeditions of the admiral Zheng He (1371–1433), a favored court eunuch of the Yongle Emperor (r. 1402–1424).

Zheng He's missions docked at ports throughout much of the Asian world, including those in Borneo, the Malay state of the Malacca Sultanate, Sri Lanka, India, Persia, Arabia, and East Africa.

[17] While maintaining foreign relations is crucial in safeguarding economic and political strength, the Imperial Court had little incentive to appease the European nations at the time.

The capability for multiple Chinese markets to satisfy domestic needs and compete globally[18] enabled independent innovation and development outside the European sphere of influence.

Given the high quality of life, adequate sanitation, and a strong internal agricultural sector,[18] the Chinese government had no significant motivation to satisfy any demands imposed by western powers.

[19] The Titsingh delegation also included the Dutch-American Andreas Everardus van Braam Houckgeest,[20] whose detailed description of this embassy to the Chinese imperial court was soon after published in the United States and Europe.

The Chinese worldview changed very little during the Qing dynasty as China's sinocentric perspectives continued to be informed and reinforced by deliberate policies and practices designed to minimize any evidence of its growing weakness and West's evolving power.