Formation of the United Kingdom

[3] After invading England, land-hungry Normans started pushing into the relatively weak Welsh Marches, setting up a number of lordships in the eastern part of the country and the border areas.

[4] Llywelyn wrestled concessions out of Magna Carta in 1215 and received the fealty of other Welsh lords in 1216 at the council at Aberdyfi, becoming the first Prince of Wales.

His grandson, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, also secured the recognition of the title Prince of Wales from Henry III with the Treaty of Montgomery in 1267.

However, a succession of disputes, including the imprisonment of Llywelyn's wife Eleanor, daughter of Simon de Montfort, culminated in the first invasion by Edward I.

With Llywelyn dead, the King took over his lands and dispossessed various other allied princes of northern and western Wales,[5] and across that area Edward established the counties of Anglesey, Caernarfonshire, Flintshire, Merionethshire, Cardiganshire and Carmarthenshire.

The exception was the lands of the Principality of Wales in the north and west of the country, which was held personally by the King (or the heir to the Crown) but was not incorporated into the Kingdom of England.

In 1404 Glyndŵr was crowned Prince of Wales in the presence of emissaries from France, Spain, and Scotland; he went on to hold parliamentary assemblies at several Welsh towns, including Machynlleth.

In 1155 Pope Adrian IV issued the papal bull Laudabiliter giving the Norman King Henry II of England lordship over Ireland.

The Normans landed in Ireland in 1169, and within a short time Leinster was reclaimed by Diarmait, who named his son-in-law, Richard de Clare, heir to his kingdom.

A peace treaty followed in 1175, with the Irish High King keeping lands outside Leinster, which had passed to Henry on the expected death of both Diarmait and de Clare.

When the High King lost his authority Henry awarded his Irish territories to his younger son John with the title Dominus Hiberniae ("Lord of Ireland") in 1185.

Over the following centuries they sided with the indigenous Irish in political and military conflicts with England and generally stayed Catholic after the Reformation.

From 1536, Henry VIII decided to conquer Ireland and bring it under crown control so the island would not become a base for future rebellions or foreign invasions of England.

From 1601, Elizabeth I's chief minister Sir Robert Cecil maintained a secret correspondence with James in order to prepare in advance for a smooth succession.

He insisted that English and Scots should "join and coalesce together in a sincere and perfect union, as two twins bred in one belly, to love one another as no more two but one estate".

However, in the ensuing hundred years, strong religious and political differences continued to divide the kingdoms, and common royalty could not prevent occasions of internecine warfare.

Over the years the settlers, surrounded by the hostile Catholic Irish, gradually cast off their separate English and Scottish roots, becoming British in the process, as a means of emphasising their "otherness" from their Gaelic neighbors.

In 1625, James was succeeded by his son Charles I, who in 1633, some years after his coronation at Westminster, was crowned in St Giles' Cathedral, Edinburgh, with full Anglican rites.

Meanwhile, in the Kingdom of Ireland, Charles I's Lord Deputy there, Thomas Wentworth, had antagonised the native Irish Catholics by repeated initiatives to confiscate their lands and grant them to English colonists.

As a result, the English Parliament refused to pay for a royal army to put down the rebellion in Ireland and instead raised its own armed forces.

By the end of the wars, the Three Kingdoms were a unitary state called the English Commonwealth, ostensibly a republic but having many characteristics of a military dictatorship.

In practise power was exercised by Oliver Cromwell because of his control over the Parliament's military forces, but his legal position was never clarified, even when he became Lord Protector.

When Cromwell died in 1658, the Commonwealth fell apart without major violence, and Charles II was restored as King of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

He was replaced not by his Roman Catholic son, James Stuart, but by his Protestant daughter and son-in-law, Mary II and William III, who became joint rulers in 1689.

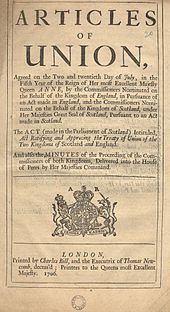

Scottish proponents believed that failure to accede to the Bill would result in the imposition of Union under less favourable terms, and the Lord Justice Clerk, James Johnstone later observed that "As for giving up the legislative power, we had none to give up... for the true state of the matter was whether Scotland should be subject to an English ministry without the privilege of trade or be subject to an English Parliament with trade."

The prospect of a union of the kingdoms was deeply unpopular among the Scottish population at large; however, following the financially disastrous Darien Scheme, the near-bankrupt Parliament of Scotland did accept the proposals.

This ban was followed by others in 1703 and 1709 as part of a comprehensive system disadvantaging the Catholic community and to a lesser extent Protestant dissenters.

[7] In 1798, many members of this dissenter tradition made common cause with Catholics in a rebellion inspired and led by the Society of United Irishmen.

In 1948 a working party chaired by the Cabinet Secretary recommended that the country's name be changed to the "United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ulster".

Its primary law-making powers were enhanced following a Yes vote in the referendum on 3 March 2011, making it possible for it to legislate without having to consult the UK parliament or the Secretary of State for Wales in the 20 topic areas that are devolved.