Forsterite

[6] In 2011 it was observed as tiny crystals in the dusty clouds of gas around a forming star.

[7] Two polymorphs of forsterite are known: wadsleyite (also orthorhombic) and ringwoodite (isometric, cubic crystal system).

Forsterite, fayalite (Fe2SiO4) and tephroite (Mn2SiO4) are the end-members of the olivine solid solution series; other elements such as Ni and Ca substitute for Fe and Mg in olivine, but only in minor proportions in natural occurrences.

Forsterite-rich olivine is a common crystallization product of mantle-derived magma.

Olivine in mafic and ultramafic rocks typically is rich in the forsterite end-member.

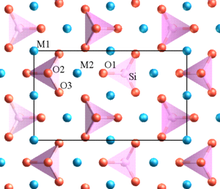

The four oxygen atoms have a partial negative charge because of the covalent bond with silicon.

Therefore, oxygen atoms need to stay far from each other in order to reduce the repulsive force between them.

The cations occupy two different octahedral sites which are M1 and M2 and form ionic bonds with the silicate anions.

This structure of forsterite can form a complete solid solution by replacing the magnesium with iron.

The occurrence of forsterite due to the oxidation of iron was observed in the Stromboli volcano in Italy.

As the volcano fractured, gases and volatiles escaped from the magma chamber.

Hence, the crystallizing olivine was Mg-rich, and igneous rocks rich in forsterite were formed.

[14] In high-pressure experiments, the transformation may be delayed so that forsterite can remain metastable at pressures up to almost 50 GPa (see fig.).

The progressive metamorphism between dolomite and quartz react to form forsterite, calcite and carbon dioxide:[15]

Forsterite reacts with quartz to form the orthopyroxene mineral enstatite in the following reaction:

It was named by Armand Lévy in 1824 after the English naturalist and mineral collector Adolarius Jacob Forster.

[16][17] Forsterite is being currently studied as a potential biomaterial for implants owing to its superior mechanical properties.