Banded iron formation

[9] A well-preserved banded iron formation typically consists of macrobands several meters thick that are separated by thin shale beds.

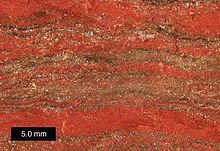

The macrobands in turn are composed of characteristic alternating layers of chert and iron oxides, called mesobands, that are several millimeters to a few centimeters thick.

BIFs tend to be extremely hard, tough, and dense, making them highly resistant to erosion, and they show fine details of stratification over great distances, suggesting they were deposited in a very low-energy environment; that is, in relatively deep water, undisturbed by wave motion or currents.

[7][5] Their iron sediments are granular to oolitic in character, forming discrete grains about a millimeter in diameter, and they lack microbanding in their chert mesobands.

[8] They also tend to show a higher level of oxidation, with hematite prevailing over magnetite,[10] and they typically contain a small amount of phosphate, about 1% by mass.

[5] In 1954, Harold Lloyd James advocated a classification based on four lithological facies (oxide, carbonate, silicate, and sulfide) assumed to represent different depths of deposition,[1] but this speculative model did not hold up.

Lake Superior BIFs are found in larger basins in association with black shales, quartzites, and dolomites, with relatively minor tuffs or other volcanic rocks, and are assumed to have formed on a continental shelf.

[17] This classification has been more widely accepted, but the failure to appreciate that it is strictly based on the characteristics of the depositional basin and not the lithology of the BIF itself has led to confusion, and some geologists have advocated for its abandonment.

[16] Because the processes by which BIFs are formed appear to be restricted to early geologic time, and may reflect unique conditions of the Precambrian world, they have been intensively studied by geologists.

[24][25][26] The banded iron formations here were deposited from 2470 to 2450 Ma and are the thickest and most extensive in the world,[4][27] with a maximum thickness in excess of 900 meters (3,000 feet).

[5] Neoproterozoic banded iron formations include the Urucum in Brazil, Rapitan in the Yukon, and the Damara Belt in southern Africa.

[30][31] With his 1968 paper on the early atmosphere and oceans of the Earth,[32] Preston Cloud established the general framework that has been widely, if not universally,[33][34] accepted for understanding the deposition of BIFs.

Such organisms would have been protected from their own oxygen waste through its rapid removal via the reservoir of reduced ferrous iron, Fe(II), in the early ocean.

For example, improved dating of Precambrian strata has shown that the late Archean peak of BIF deposition was spread out over tens of millions of years, rather than taking place in a very short interval of time following the evolution of oxygen-coping mechanisms.

[5][35] The few formations deposited after 1,800 Ma[36] may point to intermittent low levels of free atmospheric oxygen,[37] while the small peak at 750 million years ago may be associated with the hypothetical Snowball Earth.

[5] Preston Cloud proposed that mesobanding was a result of self-poisoning by early cyanobacteria as the supply of reduced iron was periodically depleted.

[5] Another theory is that mesobands are primary structures resulting from pulses of activity along mid-ocean ridges that change the availability of reduced iron on time scales of decades.

[39] In the case of granular iron formations, the mesobands are attributed to winnowing of sediments in shallow water, in which wave action tended to segregate particles of different size and composition.

[5] Plausible sources of iron include hydrothermal vents along mid-ocean ridges, windblown dust, rivers, glacial ice, and seepage from continental margins.

Heinrich Holland argues that the absence of manganese deposits during the pause between Paleoproterozoic and Neoproterozoic BIFs is evidence that the deep ocean had become at least slightly oxygenated.

[31] Banded iron formations in northern Minnesota are overlain by a thick layer of ejecta from the Sudbury Basin impact.

An asteroid (estimated at 10 km (6.2 mi) across) impacted into waters about 1,000 m (3,300 ft) deep 1.849 billion years ago, coincident with the pause in BIF deposition.

[47] On the other hand, there is fossil evidence for abundant photosynthesizing cyanobacteria at the start of BIF deposition[5] and of hydrocarbon markers in shales within banded iron formation of the Pilbara craton.

The BIFs of the Hamersley Range show great chemical homogeneity and lateral uniformity, with no indication of any precursor rock that might have been altered to the current composition.

Prior to 2.45 billion years ago, the high degree of mass-independent fractionation of sulfur (MIF-S) indicates an extremely oxygen-poor atmosphere.

The peak of banded iron formation deposition coincides with the disappearance of the MIF-S signal, which is interpreted as the permanent appearance of oxygen in the atmosphere between 2.41 and 2.35 billion years ago.

[31] Until 1992[56] it was assumed that the rare, later (younger) banded iron deposits represented unusual conditions where oxygen was depleted locally.

In a Snowball Earth state the continents, and possibly seas at low latitudes, were subject to a severe ice age circa 750 to 580 Ma that nearly or totally depleted free oxygen.

[61] Magnetite-rich banded iron formation, known locally as taconite, is ground to a powder, and the magnetite is separated with powerful magnets and pelletized for shipment and smelting.

When Japan occupied Northeast China in 1931, these mills were turned into a Japanese-owned monopoly, and the city became a significant strategic industrial hub during the Second World War.

Banded formation iron deposition peaks at the beginning of Stage 2 and pauses at the beginning of Stage 3.