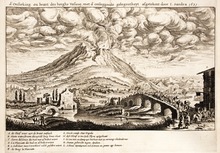

Mount Vesuvius

Vesuvius consists of a large cone partially encircled by the steep rim of a summit caldera, resulting from the collapse of an earlier, much higher structure.

It was considered a divinity of the Genius type at the time of the eruption of AD 79: it appears under the inscribed name Vesuvius as a serpent in the decorative frescos of many lararia, or household shrines, surviving from Pompeii.

[24] The cliffs forming the northern ridge of Monte Somma's caldera rim reach a maximum height of 1,132 m (3,714 ft) at Punta Nasone.

The volcano's slopes are scarred by lava flows, while the rest are heavily vegetated, with scrub and forests at higher altitudes and vineyards lower down.

Others include Campi Flegrei, a large caldera a few kilometers to the north-west, and Ischia, a volcanic island 20 kilometres (12 mi) to the west, and several undersea volcanoes to the south.

[29] Scientific knowledge of the geologic history of Vesuvius comes from core samples taken from a 2,000 m (6,600 ft) plus borehole on the flanks of the volcano, extending into Mesozoic rock.

[30] The area has been subject to volcanic activity for at least 400,000 years; the lowest layer of eruption material from the Somma caldera lies on top of the 40,000-year‑old Campanian ignimbrite produced by the Campi Flegrei complex.

[51] The Romans grew accustomed to minor earth tremors in the region; the writer Pliny the Younger even wrote that they "were not particularly alarming because they are frequent in Campania".

The flows were rapid-moving, dense and very hot, knocking down, wholly or partly, all structures in their path, incinerating or suffocating all population remaining there and altering the landscape, including the coastline.

[52] The initial major explosion produced a column of ash and pumice ranging between 15 and 30 kilometres (49,000 and 98,000 ft) high, which rained on Pompeii to the southeast but not on Herculaneum upwind.

Subsequently, the cloud collapsed as the gases expanded and lost their capability to support their solid contents, releasing it as a pyroclastic surge, which first reached Herculaneum but not Pompeii.

Another study used the magnetic characteristics of over 200 samples of roof-tile and plaster fragments collected around Pompeii to estimate the equilibrium temperature of the pyroclastic flow.

[54] The magnetic study revealed that on the first day of the eruption a fall of white pumice containing clastic fragments of up to 3 centimetres (1.2 in) fell for several hours.

This cloud and a request by a messenger for an evacuation by sea prompted the elder Pliny to order rescue operations in which he sailed away to participate.

As the ship was preparing to leave the area, a messenger came from his friend Rectina (wife of Tascius[63]) living on the coast near the foot of the volcano, explaining that her party could only get away by sea and asking for rescue.

Advised by the helmsman to turn back, he stated, "Fortune favors the brave" and ordered him to continue to Stabiae (about 4.5 km from Pompeii).

[64] In the first letter to Tacitus, Pliny the Younger suggested that his uncle's death was due to the reaction of his weak lungs to a cloud of poisonous, sulphurous gas that wafted over the group.

Along with Pliny the Elder, the only other noble casualties of the eruption to be known by name were Agrippa (a son of the Herodian Jewish princess Drusilla and the procurator Antonius Felix) and his wife.

Examination of cloth, frescoes and skeletons shows that, in contrast to the victims found at Herculaneum, it is unlikely that high temperatures were a significant cause of the destruction at Pompeii.

Herculaneum, much closer to the crater, was saved from tephra falls by the wind direction but was buried under 23 metres (75 ft) of material deposited by pyroclastic surges.

The tephra and hot ash from multiple days of the eruption damaged the fabric control surfaces, the engines, the Plexiglas windscreens and the gun turrets of the 340th's B-25 Mitchell medium bombers.

[75] Large Vesuvian eruptions which emit volcanic material in quantities of about 1 cubic kilometre (0.24 cu mi), the most recent of which overwhelmed Pompeii and Herculaneum, have happened after periods of inactivity of a few thousand years.

For Vesuvius, the amount of magma expelled in an eruption increases roughly linearly with the interval since the previous one, and at a rate of around 0.001 cubic kilometres (0.00024 cu mi) for each year.

Additionally, the removal of the higher melting point material will raise the concentration of felsic components such as silicates, potentially making the magma more viscous, adding to the explosive nature of the eruption.

In this scenario, the volcano's slopes, extending out to about 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) from the vent, may be exposed to pyroclastic surges sweeping down them, whilst much of the surrounding area could suffer from tephra falls.

It is assumed that tephra accumulation exceeding 100 kilograms per square metre (20 lb/sq ft)—at which point people are at risk from collapsing roofs—may extend out as far as Avellino to the east or Salerno to the south-east.

The plan assumes between two weeks and 20 days notice of an eruption and foresees the emergency evacuation of 600,000 people, almost entirely comprising all those living in the zona rossa ("red zone"), i.e. at greatest risk from pyroclastic flows.

[8][78] The evacuation, by train, ferry, car, and bus, is planned to take about seven days, and the evacuees would mostly be sent to other parts of the country, rather than to safe areas in the local Campania region, and may have to stay away for several months.

[80] The volcano is closely monitored by the Osservatorio Vesuvio in Ercolano with extensive networks of seismic and gravimetric stations, a combination of a GPS-based geodetic array and satellite-based synthetic aperture radar to measure ground movement and by local surveys and chemical analyses of gases emitted from fumaroles.

Mount Vesuvius' first funicular – a type of vertical transport that uses two opposing, interconnected, rail-guided passenger cars always moving in concert – opened in 1880, subsequently destroyed by the March 1944 eruption.