Franco-Indian alliance

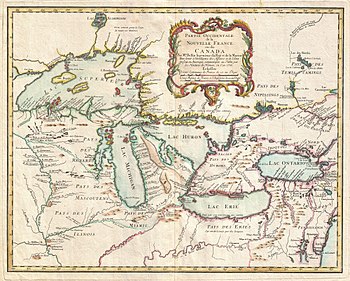

[1] The alliance involved French settlers on the one side, and indigenous peoples such as the Abenaki, Odawa, Menominee, Winnebago, Mississauga, Illinois, Sioux, Huron, Petun, and Potawatomi on the other.

[2] It allowed the French and the natives to form a haven in the middle-Ohio valley before the open conflict between the European powers erupted.

Natives also adopted French habits, like chief Kondiaronk who wanted to be buried in his uniform of captain or Kateri Tekakwitha who became a Catholic Saint.

In North America in the 18th century, the British outnumbered the French 20 to 1, a situation that urged France to ally with the majority of the First Nations.

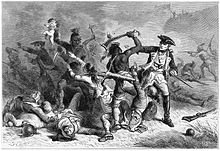

[9] During the American War of Independence and the onset of the Franco-American alliance, the French would again combine with Indian troops, as in the Battle of Kiekonga in 1780 under Augustin de La Balme.