Frank Russell, 2nd Earl Russell

[1][2] Unconventional for their time, the Amberleys believed in birth control, feminism, political reforms then considered radical (including votes for women and the working classes) and free love, and lived according to their ideals.

The family lived at Rodborough house (near Stroud), which belonged to the viscount's father, and then at Ravenscroft Hall, near Trellech, where Frank was allowed to do much as he pleased, including roaming the countryside.

By age eight, he had read, for pleasure, the complete works of Sir Walter Scott, and began a lifelong love of science and engineering by attending the Royal Society's lectures for children.

[7] This took Frank from what he later called the "free air of Ravenscroft" where he could wander as he wished, to his grandparents' home at Pembroke House, where he was closely supervised and confined to the grounds.

[8] The earl was by then past 80, two decades older than his wife, and spent many of his waking hours reading: the house was dominated by Lady Russell,[9] who employed a strict moral code in raising the boys.

It was Sarah Richardson that Santayana was thinking of in making his statement; she later defended Frank Russell as his marital problems filled the daily papers, and he was devastated by her death in 1909.

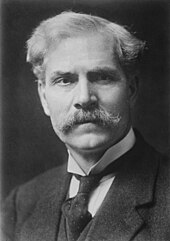

[32] He was a tall young man of twenty, still lithe though large of bone, with abundant tawny hair, clear little steel-blue eyes, and a florid complexion.

Although the monotony of life in the London suburbs was varied by guests such as Oscar Wilde, Russell was resentful at how he had been treated at Oxford and in October 1885, took ship for the United States.

An expensive lifestyle and fees from the many court actions he was involved in would lead him to describe himself as bankrupt by 1921, and when Frank died ten years later, Bertrand said he had inherited a title from his brother but little else.

[36] Although Russell was not wealthy by the standards of British nobility, what he did have, including his title, was enough to make him the target of parents seeking suitable matches for their daughters.

"[41] Late in 1890, Mabel sued unsuccessfully to judicially separate from him, accusing him in the process of "immoral behaviour" with another university friend, Herbert Roberts, head mathematics tutor at Bath College.

[45] Despite the lull in the Russell matrimonial litigation, detectives were active for both sides, hoping to find evidence of adultery which would allow their employer advantage in the courts.

[54][55] Russell and Mollie Somerville journeyed to Chicago, but learned that local laws had recently been tightened, and required a year's residence, with other restrictive provisions.

[56] They honeymooned on the way to America's East Coast, including at Denver's Brown Palace Hotel, where Russell told a reporter that a charge of bigamy would never stick.

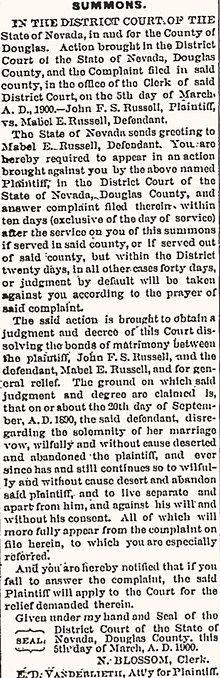

[59] Beginning when Russell wired news of his Nevada marriage to appear as a notice in The Times, there was considerable press interest on both sides of the Atlantic in what had occurred.

[63] The Russell family always believed that the earl was prosecuted at the behest of the new king, Edward VII, who had a chequered past and several mistresses while on the throne, to boost his own reputation for morality.

[62] Russell was bailed, and following a hearing at Bow Street Magistrates' Court on 22 June,[64] he was indicted for bigamy by a grand jury and committed for trial.

[72] This required the suspension of the courts over which they would have presided that day, and some newspapers questioned the cost of the spectacle, which included the expense of bringing over Curler from Nevada and housing him for two months.

at Winchester Coll., and at Balliol Coll., Oxford; is a County Alderman for London; tried and convicted by his Peers at Westminster 1901 on a charge of felony, in that he had contracted a bigamous marriage in Nevada, U.S.A., on April 15th, 1900, with Mollie Cooke: m. 1st, 1890, Mabel Edith ( who obtained a divorce in England 1901), dau.

Russell spent part of his time in prison peppering the home secretary, Charles Ritchie, with petitions for his early release (which he did not gain) and for better conditions and more privileges (which, mostly, he received).

[86] The marriage with Mollie was generally a success in its early years; according to Russell's biographer, Ruth Derham, she "genuinely loved him, understood that he must be master in his own house... her outside interests provided them both with a degree of independence.

[93] Two weeks before his death in 1931 Frank Russell wrote to Santayana that he had received two great shocks in his life, when Jowett sent him down from Oxford, and "when Elizabeth left me I went completely dead and have never come alive again.

Von Arnim famously caricatured Russell in her 1921 novel Vera, a depiction that greatly angered him, and when Elizabeth heard of her husband's death in 1931 she said she was "never happier in her life".

[95] Russell had continued to take liberal stances in the House of Lords, strongly supporting the Parliament Act 1911, which diminished its powers, and in December 1912 joined the Fabian Society, the first peer to do so.

[97] By late 1917, though, Bertrand had become disillusioned with his cause and Frank met with General George Cockerill of the War Office, resulting in agreement within the government on 17 January 1918 that the banning order should be lifted.

He began his tenure by stating that Indian independence was "at this moment impossible", something which although quickly retracted, Nehru concluded was the true attitude of the British government.

"[110] Benn regretted Russell's death "not only because it deprives the India office of a distinguished political figure but because of the personal loss of a brilliant, kindly friend".

Throughout his life, his strong identification with his youthful self, misunderstood, persecuted, and wronged, led him to seek reforms that benefited many an underdog, but also made him 'suspect the satisfied', 'distrust the majority', impatient with acquaintance and unsuccessful in love.

"[114] Ann Holmes, in her chapter on the Russell divorce cases, stated that in late Victorian England, "marital fidelity was not as important as the appearance of a stable marriage and happy home; scandal was more shameful than adultery.

[83] Peter Bartrip concluded his biographical sketch of Russell, It is hard to warm to Frank but easier to excuse, or at least explain, his character in terms of genetic inheritance, peculiar upbringing and the childhood tragedies that cost him most of his immediate family.