Franz Joseph I of Austria

In December 1848, Franz Joseph's uncle Emperor Ferdinand I abdicated the throne at Olomouc, as part of Minister President Felix zu Schwarzenberg's plan to end the Hungarian Revolution of 1848.

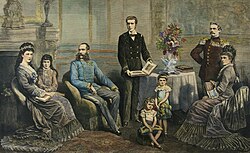

He ruled peacefully for the next 45 years, but personally suffered the tragedies of the execution of his brother Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico in 1867, the suicide of his son Rudolf in 1889, and the assassinations of his wife Elisabeth in 1898 and his nephew and heir presumptive, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in 1914.

After the Austro-Prussian War, Austria-Hungary turned its attention to the Balkans, which was a hotspot of international tension because of conflicting interests of Austria with not only the Ottoman but also the Russian Empire.

On 28 June 1914, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo resulted in Austria-Hungary's declaration of war against the Kingdom of Serbia, which was an ally of the Russian Empire.

For this reason, Franz Joseph was consistently built up as a potential successor to the imperial throne by his politically ambitious mother from early childhood.

In addition, the archduke received general education that was customary at the time (including mathematics, physics, history, geography), which was later supplemented by law and political science.

[5] Following Austria's victory over the Italians at Custoza in late July 1848, the court felt it safe to return to Vienna, and Franz Joseph travelled with them.

Franz Joseph was also almost immediately faced with a renewal of the fighting in Italy, with King Charles Albert of Sardinia taking advantage of setbacks in Hungary to resume the war in March 1849.

Unlike other Habsburg ruled areas, the Kingdom of Hungary had an old historic constitution,[8] which limited the power of the crown and had greatly increased the authority of the parliament since the 13th century.

Sensing a need to secure his right to rule, Franz Joseph sought help from Russia, requesting the intervention of Tsar Nicholas I, in order "to prevent the Hungarian insurrection developing into a European calamity".

[19] With order now restored throughout his empire, Franz Joseph felt free to renege on the constitutional concessions he had made, especially as the Austrian parliament meeting at Kremsier had behaved—in the young Emperor's eyes—abominably.

[21] The survival of Franz Joseph was also commemorated in Prague by erecting a new statue of St. Francis of Assisi, the patron saint of the emperor, on Charles Bridge.

Franz Joseph was crowned King of Hungary on 8 June, and on 28 July he promulgated the laws that officially turned the Habsburg domains into the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary.

Her influence helped build the trust necessary for successful negotiations, and her personal popularity in Hungary significantly bolstered the monarchy's legitimacy in the region.

[30] Following the accession of Franz Joseph to the throne in 1848, the political representatives of the Kingdom of Bohemia hoped and insisted that account should be taken of their historical state rights in the upcoming constitution.

In 1867, the Austro-Hungarian compromise and the introduction of the dual monarchy left the Czechs and their aristocracy without the recognition of separate Bohemian state rights for which they had hoped.

In Bohemia, opposition to dualism took the form of isolated street demonstrations, resolutions from district representations, and even open air mass protest meetings, confined to the biggest cities, such as Prague.

Under Minister-President Karl Hohenwart in 1871, the government of Cisleithania negotiated a series of fundamental articles spelling out the relationship of the Bohemian Crown to the rest of the Habsburg Monarchy.

In Vienna in 1909 he helped Hinko Hinković's defense in the fabricated trial against prominent Croats and Serbs members of the Serbo-Croatian Coalition (such as Frano Supilo and Svetozar Pribićević), and others, who were sentenced to more than 150 years and a number of death penalties.

[32] This was justified on grounds of precedence; from 1452 to the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, with only one brief period of interruption under the House of Wittelsbach, the Habsburgs had generally held the German crown.

[33] However, Franz Joseph's desire to retain the non-German territories of the Habsburg Austrian Empire in the event of German unification proved problematic.

[clarification needed] That omission was addressed in the Three Emperors' League agreement of 1881, when both Germany and Russia endorsed Austria-Hungary's right to annex Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The Russian foreign minister, Count Mikhail Muravyov, stated that an Austrian annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina would raise "an extensive question requiring special scrutiny".

Austria's foreign minister, Alois von Aehrenthal, pursued this offer vigorously, resulting in the quid pro quo understanding with Izvolsky, reached on 16 September 1908 at the Buchlau Conference.

However, Izvolsky made this agreement with Aehrenthal without the knowledge of Tsar Nicholas II or his government in St. Petersburg, or any of the other foreign powers including Britain, France and Serbia.

Based upon the assurances of the Buchlau Conference and the treaties that preceded it, Franz Joseph signed the proclamation announcing the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina into the Empire on 6 October 1908.

His death was a result of developing pneumonia of the right lung several days after catching a cold while walking in Schönbrunn Park with King Ludwig III of Bavaria.

However, Franz Joseph fell deeply in love with Néné's younger sister Elisabeth ("Sisi"), a beautiful girl of 15, and insisted on marrying her instead.

Sophie acquiesced, despite her misgivings about Sisi's appropriateness as an imperial consort, and the young couple were married on 24 April 1854 in St. Augustine's Church, Vienna.

Although the emperor received letters from members of the imperial family throughout the fall and winter of 1899 beseeching him to relent, Franz Joseph stood his ground.